Having reviewed UN system funding by entity and financial instrument, we now turn to the sources of this funding. Figure 7 presents a breakdown of the UN system’s total revenue for 2023 (US$ 67.6 billion) by contributor type. As can be seen, the UN system is financed by a diverse range of partners, including governments; multilateral financing mechanisms and institutions; private sector entities; foundations; and other non-state funding. Additionally, a portion of revenue is derived from activities not attributable to a specific contributor, such as investments or currency exchange rate gains.

Governments remain the primary source of funding for the UN system. In 2023, direct government contributions accounted for 69% of UN system revenue, or US$ 46.4 billion – a US$ 7.4 billion decrease compared to 2022 and roughly 3% below the average for the 2015–2023 period. Within this category, OECD-DAC members contributed US$ 36.9 billion, representing 55% of total UN revenue, and non-OECD-DAC governments US$ 9.4 billion, or 14% of the total. A further US$ 12.5 billion, equivalent to 18% of total revenue, came via multilateral funding channels, such as the European Union and inter-agency pooled funds, which are also largely government financed. These figures underscore the central role that governments continue to play in financing the UN system (see also Figure 7).

Revenue from Member States

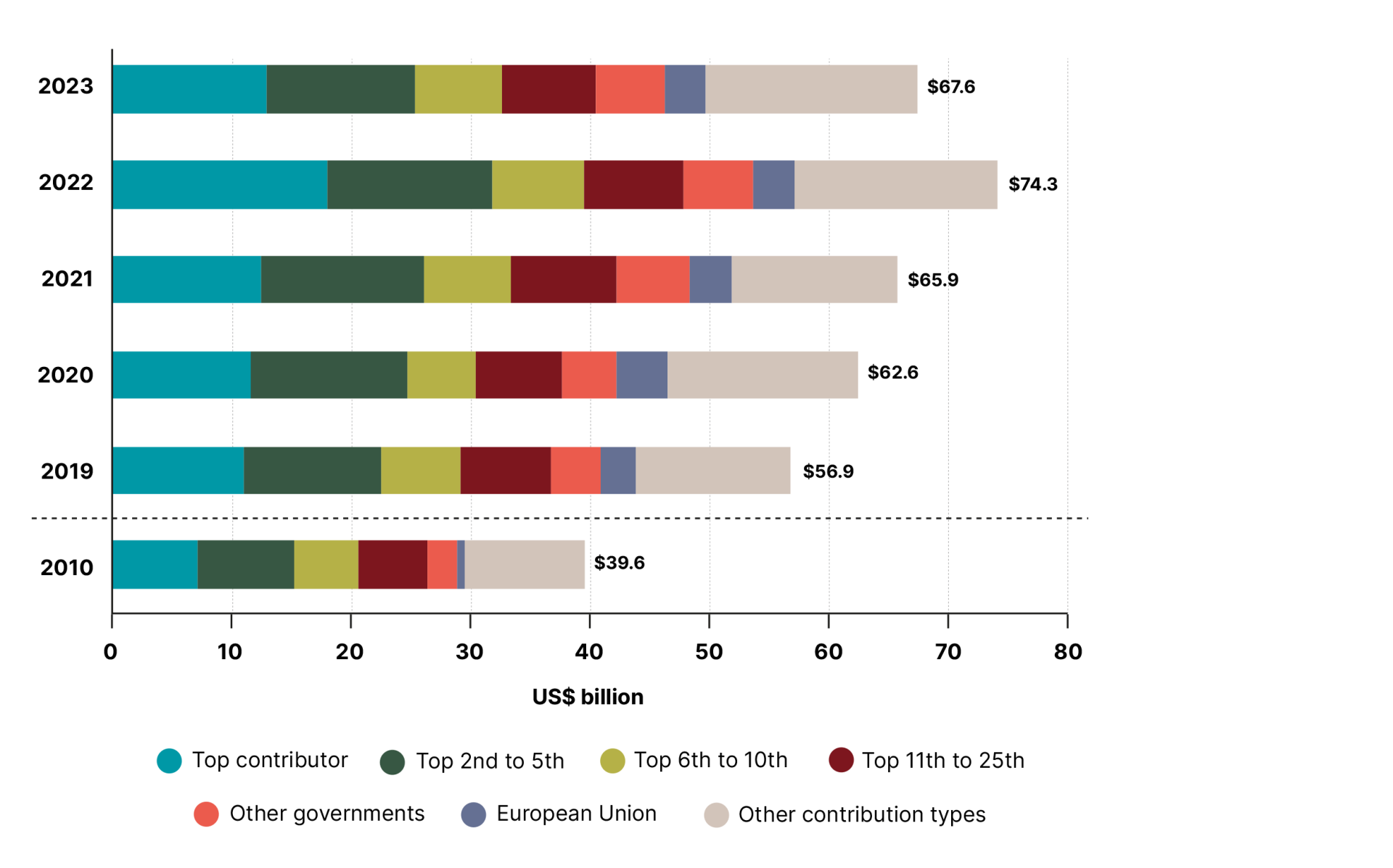

Figure 8 illustrates the composition and overall volume of UN system contributions in 2010, and from 2019 to 2023, disaggregated by tiers of government contributors, the EU, and other contributor types. It provides insight into both the evolution of total funding and the distribution between contributor groups.

The United States is the top contributor to the UN system. In 2022, it provided a total of US$ 18.1 billion, an increase of US$ 5.6 billion compared to the previous year. In 2023, contributions declined to US$ 13.0 billion – US$ 5.1 billion less than 2022 but still US$ 0.5 billion higher than in 2021. More than 60% of the US’s 2023 funding was directed at four UN entities, with WFP receiving the largest share of funding at 24% (US$ 3.1 billion), down from 40% in 2022.

UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, received 15% (US$ 1.9 billion), up from 12% the previous year; UN-DPO 13% (US$ 1.8 billion), compared to 10% in 2022; and IOM 11% (US$ 1.4 billion), more than doubling the 5% share it received the previous year.

The top five contributors, represented by the two left-most segments in Figure 8’s bars, collectively accounted for 38% of total contributions in 2023, a similar level to 2010 (39%). When expanded to include the top ten contributing governments, it can be seen that this larger group has consistently provided about half the UN system’s total revenue throughout the 2019–2023 period. As of 2023, their combined share stood at 48%. This sustained concentration highlights the UN system’s continued dependency on a relatively small group of major donors.

UN system funding by Member States and other contributors, 2010–2023 (US$ billion)

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB).

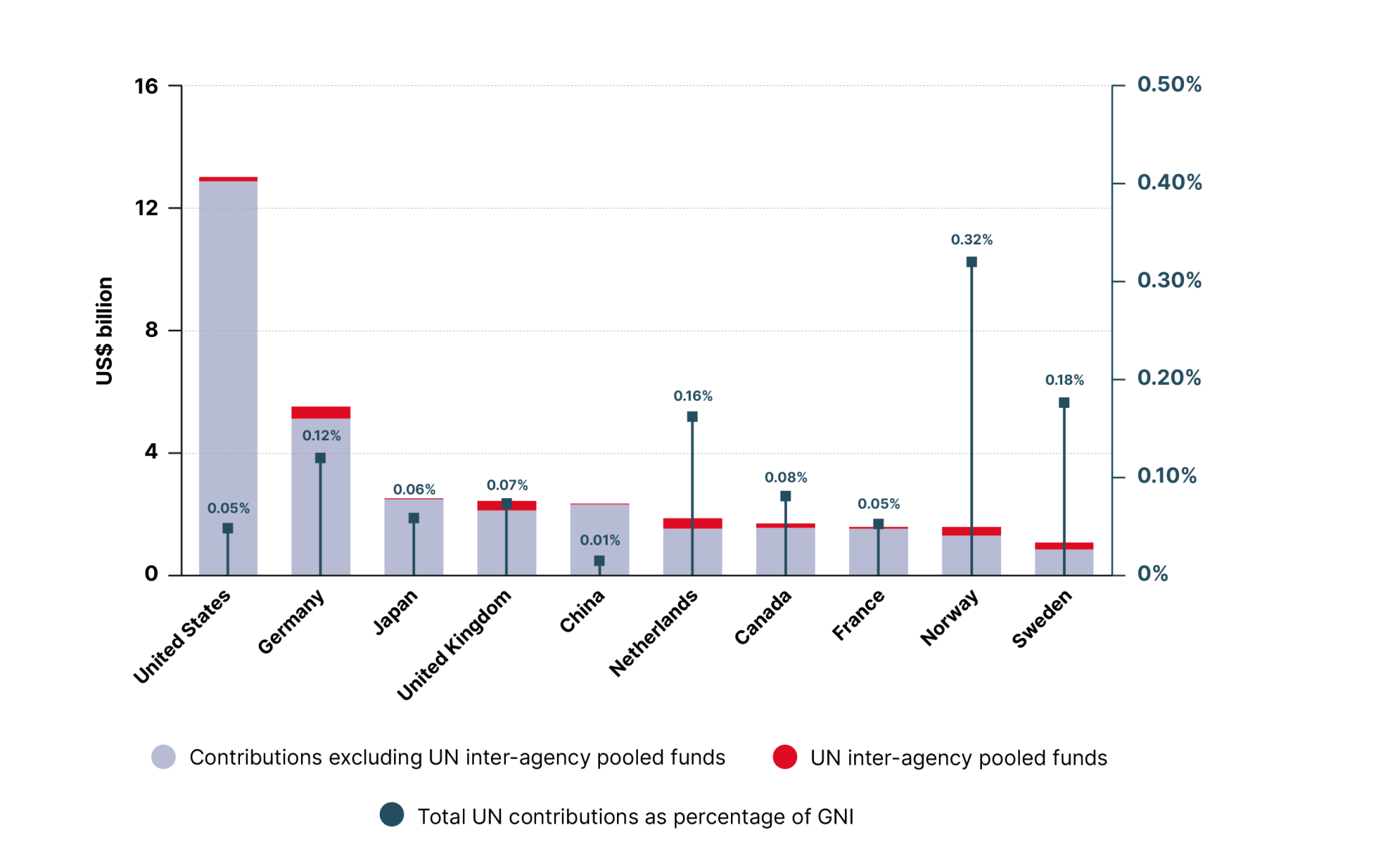

The top ten Member State contributors have remained largely consistent since 2015, the year in which China – the only non-OECD-DAC country among them – emerged as part of the group. Figure 9 presents the top government contributors to the UN system in 2023, ranked by both absolute contributions (in US$ billions) – consisting of contributions reported by UN entities to the CEB, as well as those provided via inter-agency pooled funds – and contributions relative to each country’s gross national income (GNI). This dual perspective allows for an evaluation of not only the scale of financial support, but the proportional effort made by each Member State in relation to their economic capacity.

The United States was the top contributor to the UN system in 2023, substantially ahead of all the other donors in absolute terms. When measured as a share of GNI, however, its contribution stands at 0.05%, reflecting a smaller proportion of national income allocated to UN funding compared to other major donors. By contrast, although Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands do not rank among 2023’s top five donors in absolute terms, they were the leading contributors in terms of share of GNI, at 0.32%, 0.18% and 0.16% respectively.

During the 2010–2023 period, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom consistently ranked among the top 5 contributors to the UN system in absolute terms. Germany has held the second position since 2016, and in 2023 its contribution amounted to 0.12% of its GNI. It is also worth noting that, having been the 14th largest contributor to the UN system in 2010, China has ranked fifth every year since 2019 (except for 2021, when it ranked sixth). These various contributions, in conjunction with those from Canada and France, are indicative of strong policy commitments to international cooperation and multilateral financing through the UN.

Returning to Figure 8, contributions from the top 11th to 25th donors, along with the segment representing ‘other governments’, have fluctuated from year to year. Combined, they increased from US$ 8.2 billion in 2010 to US$ 13.6 billion in 2023, representing 20% of total UN system revenue. This points to the widespread engagement of emerging economies and Member State contributors in supporting the UN’s work.

Revenue provided by non-Member State contributors nearly doubled over the same period, rising from US$ 10.7 billion in 2010 to US$ 21.2 billion in 2023. Within this group, the EU – a political and economic union of 27 member states – increased its contributions from US$ 0.7 billion in 2010 to $3.5 billion in 2023. While the EU is not a UN Member State, it holds enhanced observer status at the UN General Assembly and is a critical partner in achieving the UN system’s global mandates. EU contributions to the UN Secretariat and various UN agencies are examined further in the next section.

Top Member State contributors to the UN system, 2023 (US$ billion and percentage share of GNI)

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB), UN Pooled Funds Database, and UN Statistics Division (UNSD).

Revenue from multilateral channels

The UN system is also funded by a diverse set of multilateral institutions and funding mechanisms that are, in turn, primarily financed by governments. The EU is funded entirely by its member states, while IFIs such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) rely on member contributions, bond issuance and borrowing arrangements. In 2023, 93% of the total contributions received by UN inter-agency pooled funds – another multilateral channel – were provided by governments.

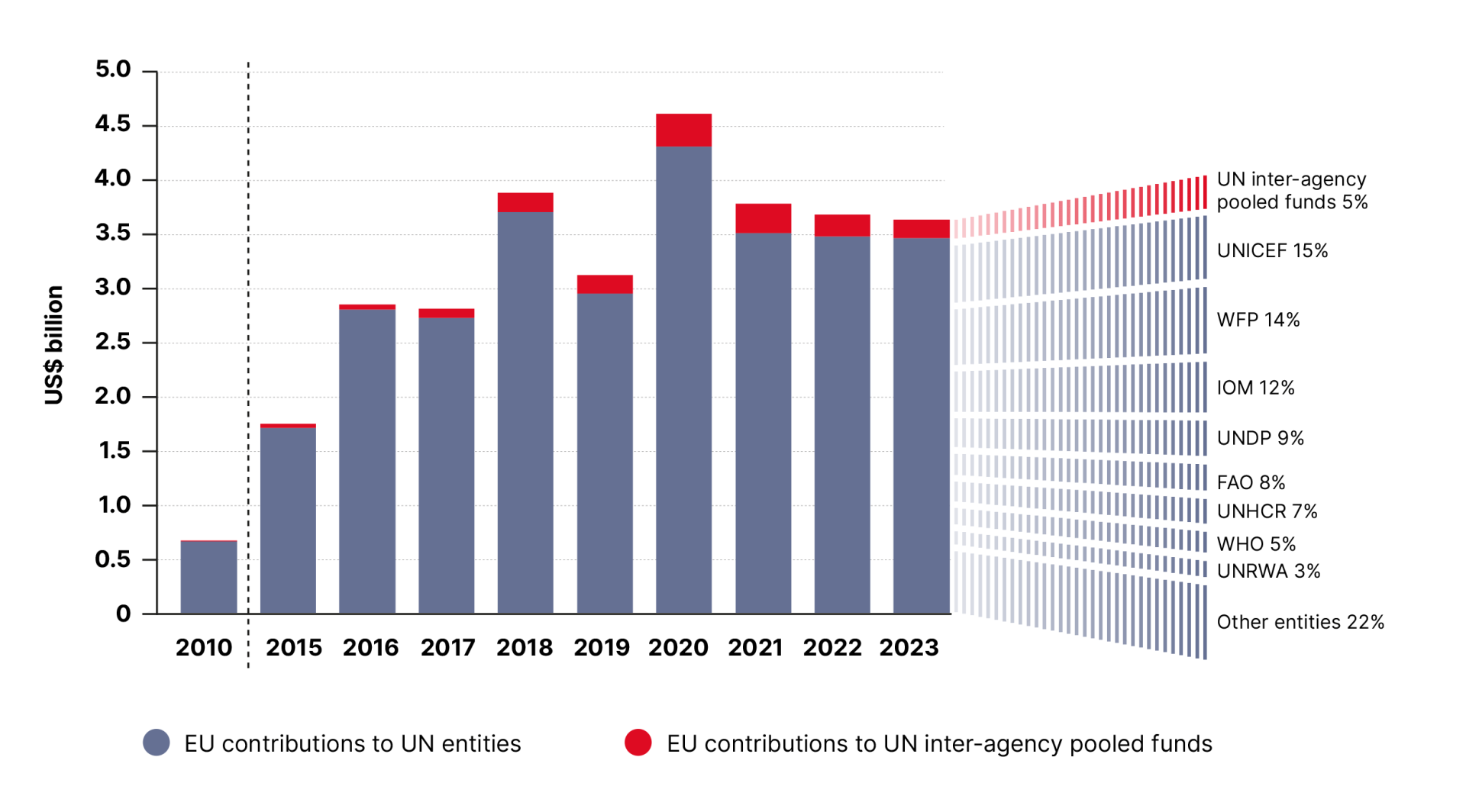

The EU acts as a significant financial partner to the UN system. Given that it is, legally and structurally, a political and economic union of member states, the EU does not typically provide assessed or voluntary core contributions to the UN system. It does, however, channel significant levels of earmarked funding to UN entities. Figure 10 illustrates the levels of EU funding to the UN system, including resources provided through UN inter-agency pooled funds, for 2010 and 2015–2023. The data includes a panel showing the distribution of 2023 contributions by main recipient entities. As can be seen, EU contributions increased substantially between 2010 (US$ 0.7 billion) and 2018 (US$ 3.9 billion), before reaching a 2020 peak of US$ 4.6 billion in response to global needs arising from the COVID-19 pandemic. From 2021 to 2023, contributions remained largely stable at approximately US$ 3.6–3.7 billion per year, reflecting sustained engagement amid ongoing global financial pressures.

EU funding to the UN is almost entirely allocated towards humanitarian and development assistance, with UNICEF, WFP and IOM together receiving 41% of total EU funding in 2023. The EU is also one of the main funding partners for UN inter- agency pooled funds, providing US$ 166 million in 2023 – equivalent to 5% of the EU’s total contributions to the UN system.

Global vertical funds represent another major source of multilateral funding to the UN system. Similar to UN inter-agency pooled funds, global vertical funds are multi-stake-holder platforms with a targeted programmatic focus and diverse funding sources. Such funds reflect a growing trend among major contributors towards earmarking non-core resources for specific purposes,23 typically supporting clearly defined development domains conducive to demonstrable outcomes. Their governance structures are mixed, involving governments and – in some cases – civil society and the private sector.

While vertical funds are not directly administered by UN entities, and the UN does not play a lead role in fund allocations, UN entities do receive resources as implementing partners. The UN system received US$ 3.0 billion through global vertical funds in 2023, with three World Bank-administered funds – the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria; Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance; and the Global Environment Facility (GEF) – accounting for over 75% of this amount.

EU funding to the UN system, 2010–2023 (US$ billion)

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB) and UN Pooled Funds Database.

A further multilateral financing channel for the UN system are IFIs, which provide resources to support development outcomes in partnership with UN entities. Key institutions include the World Bank Group, the IMF, and regional development banks such as the African Development Bank (AfDB), Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). These multilateral organisations – funded and governed primarily by Member States – offer loans, grants and policy advice for a range of development priorities, including infrastructure, education, health and economic reform.

Direct financial flows from IFIs to the UN system amounted to US$ 2.1 billion in 2023, or 3.2% of total revenue. This figure does not, however, capture the full extent of collab-oration between IFIs and UN entities, which often involves other forms of partnerships aimed at catalysing additional resources for SDG achievement.

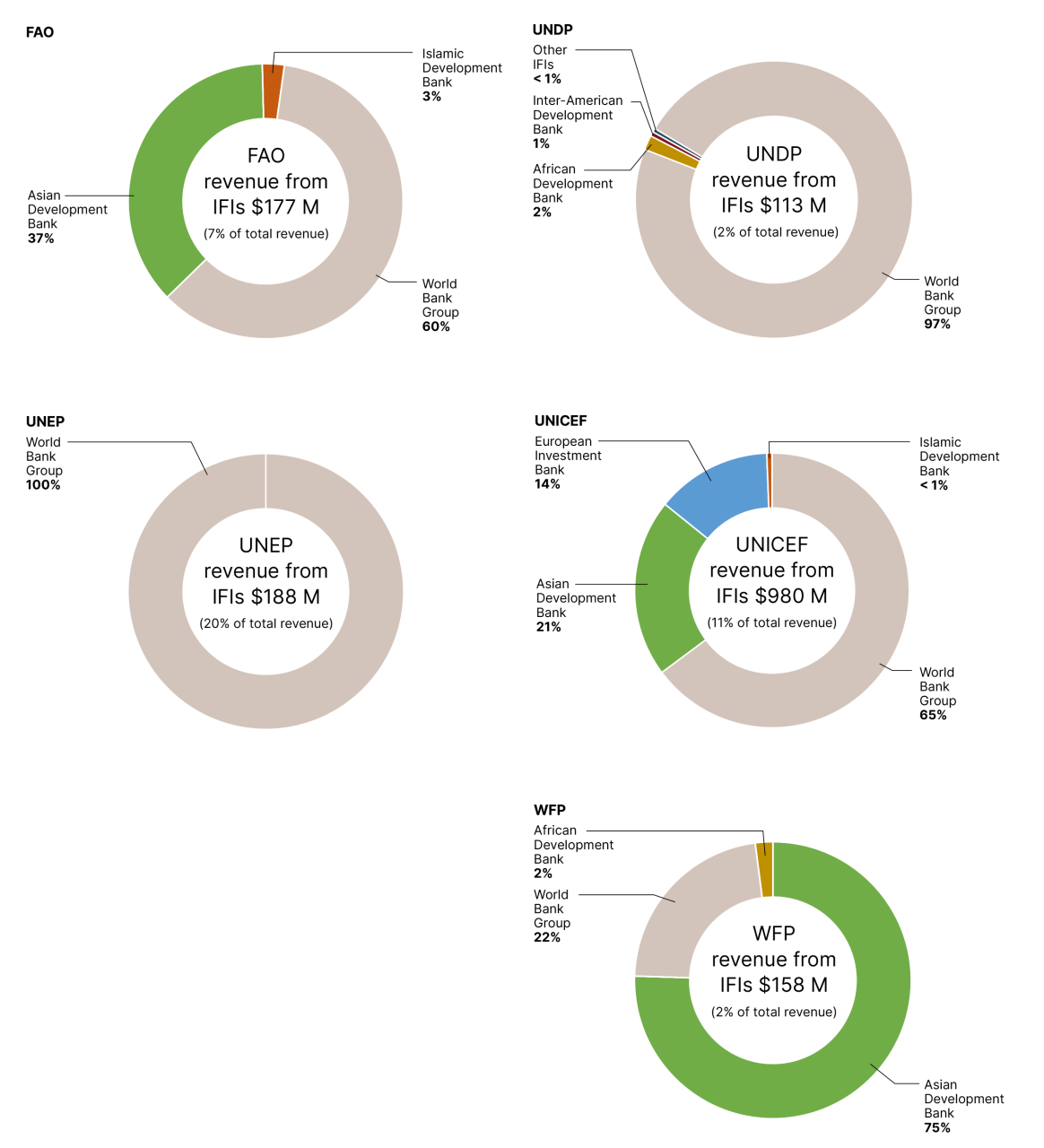

Figure 11 illustrates funding received from IFIs in 2023 as it applies to a selection of UN entities where such revenue plays a significant role. Overall, the World Bank Group is the main contributing partner, alongside several regional development banks. On the other side of the equation, UNICEF remains the biggest recipient, with 11% (US$ 980 million) of its total revenue ascribable to IFI funds. While not traditional donors, IFIs are critical partners when it comes to large-scale government financing in support of national development efforts. In this respect, UNICEF collaborates with IFIs to help mainstream child-sensitive planning, budgeting and programming.24 The World Bank Group provided US$ 633 million in direct funding to UNICEF in 2023 – the largest IFI contribution to the UN system.

UNOPS has also actively engaged in collaborative partner-ships with IFIs, receiving US$ 351 million from these multilateral institutions in 2023, equivalent to 27% of its total revenue. As illustrated in Figure 11, revenue received by UNOPS from IFIs is heavily concentrated, with 90% of such contributions originating from the World Bank Group.

A similar pattern can be seen in the cases of the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) and UNDP, which respectively received US$ 188 and US$ 113 million in IFI contribut ions, almost all of which came from the World Bank Group. World Bank Group contributions accounted for 20% of UNEP’s total revenue in 2023, reflecting its strong role as an implementing agency for GEF, which funds projects in developing countries related to biodiversity, climate change, international waters, land degradation, ozone layer depletion and persistent organic pollutants.25 Similarly, UNDP continues to strengthen its IFI engagement portfolio in order to help countries access the capital, technical expertise and strategic partnerships needed to advance the SDGs.26

In 2023, the most prominent regional development bank–UN entity funding partnership in terms of volume of resources was between the ADB and UNICEF (US$ 205 million). The two organisations work together to strengthen social service delivery in ADB countries of operation, with an emphasis on improving access to and quality of services for children, adolescents, women and disadvantaged populations.27 Turning to the WFP, of the US$ 158 million it received from IFIs – representing 2% of its total revenue – three-quarters originated from the ADB. This funding supported the delivery of critical food assistance to more than 1.3 million acutely food insecure people in Afghanistan.28

International Financial Institutions (IFIs) funding to six select UN entities, 2023 (US$ million)

Source: Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB).

Revenue from other non-state funding

Several UN entities have intensified their efforts to diversify funding sources by expanding fundraising from private sector businesses, foundations, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and individuals. Contributions from these sources are collectively referred to as ‘other non-state funding’. Figure 12 provides an overview of UN system revenue from these sources, accompanied by two side panels illustrating UN entity engagement with, respectively, the private sector and foundations. Non-state funding increased from US$ 2.8 billion in 2018 (5% of total UN system revenue) to US$ 4.8 billion in 2023 (7% of total revenue). In between, this source of funding peaked at US$ 6.1 billion in 2022, equivalent to 8% of total revenue.

The private sector remains the largest source of other non-state funding to the UN system. Its support rose from US$ 2.0 billion in 2018 to a peak of US$ 4.2 billion in 2022, before declining to US$ 3.2 billion in 2023. This trend points to the increasing role played by corporate and philanthropic partnerships in UN financing, particularly for UNICEF, UNHCR, WFP and WHO – as depicted in the side panels. In 2023, private sector income accounted for 23% (US$ 2.1 billion) of UNICEF’s total revenue. This was mobilised through private sector fundraising conducted by UNICEF’s National Committees and Country Offices, and included contributions from individuals, businesses, philanthropists and membership- and faith-based organisations. The top three private sector partners for UNICEF in 2023 were the National Committees based in the United States, Japan and Germany.29

The role of foundations and NGOs as funding partners to the UN system has also grown in recent years, though at varying scales. Contributions from foundations rose from US$ 0.5 billion in 2018 to US$ 0.9 billion in 2023, down from a peak of US$ 1.6 billion in 2022. This upward trend underscores the increasing engagement of philanthropic institutions in multilateral development and humanitarian financing. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (which in 2024 was renamed the Gates Foundation) financed more than half (52%) of the total contributions to the UN system made by foundations in 2023. By contrast, contributions from NGOs remained relatively modest and stable over the 2018–2023 period, fluctuating between US$ 0.2 and US$ 0.3 billion – although this excludes UNHCR’s national committees, which were reclassified as NGOs for the 2023 figures, bringing in US$ 0.4 billion (compared to US$ 0.5 billion in 2022, when they were classified as foundations).

Revenue from no contributor

Funding attributed to ‘no contributor’ more than doubled between 2022 and 2023, from US$ 1.7 billion to US$ 3.9 billion, representing 6% of the UN system’s total revenue. The increase is primarily explained by higher amounts recorded under the sub-category ‘other revenue – specific to the UN entity’, which includes financial gains from investments. Such gains may have been partly driven by higher cash balances carried forward from 2022, when the UN system registered revenue of US$ 74.3 billion and expenses of US$ 67.5 billion (see also Box 1). The availability of unspent funds, combined with rising global interest rates, created favourable conditions for increased investment income.

Overall, funding to the UN system from government, multi - lateral and non-state sources declined in 2023 compared to 2022 levels, indicating a tightening of funding environments and shifting donor priorities amid global economic uncertainty. This downturn followed a peak in 2022, a year marked by exceptional resource mobilisation in response to global crises, including the war in Ukraine and the ongoing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2023, government contributions – the primary source of UN funding – fell by US$ 7.4 billion, while other non-state funding declined by US$ 1.3 billion. Only ‘no contributor’ funding grew, by US$ 2.2 billion.