The SDGs are a set of 17 interconnected global goals adopted by all UN Member States in 2015 as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. They represent a call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure peace and prosperity for all. Achieving the goals requires collective action from governments, the private sector and civil society, both at the national and international level. Thus, the SDG framework has become a platform for joint action towards addressing social, economic and environmental challenges, and achieving a better, more sustainable future.

Considerable progress has been made in ensuring financial reporting by UN entities to the CEB is aligned with the SDGs. In 2018, only 11 UN entities reported their expenditures as linked to SDGs – by 2022, this figure had risen to 40. The reporting follows UN Data Standards for aligning expenditure to the SDGs, including the common methodology established for tracking the contribution made by UN activities to the 17 SDGs and their 169 targets. Notably, four entities reported their expenses as linked to the SDGs for the first time in 2022: the UN Secretariat, UNAIDS, UNEP and IRMCT.

The advances made in ensuring financial expenditure reporting is aligned to SDG goals have not necessarily extended to improving the tracking of each UN entity’s contribution towards achievement of the SDG targets. While reporting expenses at a target level is strongly advised by the Data Standards, only about half of the SDG expenditures were linked to SDG targets, US$ 28.3 billion in expenditures (of 14 UN entities). Moreover, the Data Standards recognise that certain entities may have expenditure that can only be allocated to an SDG more broadly rather than specific targets.

In 2022, 40 UN entities reported US$ 57.6 billion in allocations aligned with SDG goals, accounting for 85% of the total UN system expenditure of US$ 67.5 billion. Figure 33 illustrates how this was distributed among the 17 SDGs, with expenditure directed towards eradicating hunger (SDG 2), ensuring health and well-being (SDG 3), and promoting peace, justice and strong institutions (SDG 16) accounting for 58% of these resources.

The distribution of resources across SDGs varies significantly between UN entities. Specialised agencies often prioritise SDGs aligned with their core mission: for instance, UN-DPO, the ICC and IRMCT focus exclusively on SDG 16, while WHO dedicated 97% of its expenditure to SDG 3. Other entities may primarily support achievement of a particular SDG while also contributing to a broader spectrum of SDGs: for example, ILO allocates 60% of its expenditure to promoting decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), while also contributing to SDG 16, reducing inequalities (SDG 10), partnerships (SDG 17) and promoting gender equality (SDG 5). Certain UN entities, such as the UN Secretariat and UNDP, contribute to all the SDGs, highlighting the integrated, interdependent nature of the global goals.

The substantial expenditure aligned with SDG 2 in 2022 (US$ 13 billion) underscores the challenges currently faced by global food supply systems. Of the expenditure reported by WFP (US$ 12.2 billion), 85% was aligned Part One — Where is UN funding allocated? to SDG 2 (US$ 11.1 billion) (See Figure 33). Additionally, the conflict in Ukraine has introduced another threat to global food security given that Ukraine and the Russian Federation are between them responsible for supplying half the world’s global wheat and maize exports (30% and 20% respectively), and are also major exporters of fertilisers.40

SDG 16 was the subject of the second-largest volume of financial resources reported in 2022 (US$ 11.8 billion). Peacekeeping operations, led by UN-DPO, account for 60% of this expenditure, while the majority of the 12% share provided by the UN Secretariat went towards peacebuilding missions under UN-DPPA. The allocations to SDG 16 are closely linked to the surge in violent conflicts worldwide, underlining how ending armed conflict, enhancing institutions, and implementing inclusive, equitable legislation to safeguard human rights is pivotal to promoting sustainable development.

Procurement of goods such as food or vaccines involves a series of structured transactional operations, including the issuance of requests for proposals, supplier selection and drawing up contracts, all of which facilitates straightforward record-keeping. By contrast, measuring normative work – which involves setting standards, guidelines and regulations – can be more challenging, as its impacts lack targets that can be quantified monetarily. While other indicators, such as compliance levels and changes in behaviour, can provide insights into the effectiveness of normative standards, it is important to recognise that correlating UN entity allocations to SDG impact does not provide a correct picture. Normative work and support for national development policies may not require large financial resources but can nonetheless have a substantial impact on sustainable development.

It should be highlighted that, considering the high priority given to preserving the environment and combatting climate change, UN allocations to the relevant SDGs appear relatively low. In 2022, only US$ 3.6 billion, or 5% of total UN system expenditure, was linked to the SDGs dedicated to water and sanitation (SDG 6), clean energy (SDG 7), climate action (SDG 13), life below water (SDG 14), and life on land (SDG 15).

Figure 34 highlights which entities are contributing to the above-mentioned climate and environment-related goals, as well as selected goals related to the SDGs’ socioeconomic dimension, namely zero hunger (SDG 2), good health and well-being (SDG 3), quality education (SDG 4) and gender equality (SDG 5).

With the UN Secretariat reporting 56% of its expenditures as linked to the SDGs in 2022, the breakdown of SDG expenses by UN entities has changed compared to last year’s Financing the UN Development System report. The three main SDGs to which the UN Secretariat allocated resources are SDG 16 (32%), SDG 17 (15%) and SDG 5 (10%). In particular, the UN Secretariat’s contribution to SDG 5 represented an important share in allocations towards achievement of the goal. As can be seen in Figure 32, the UN Secretariat was responsible for 21% of the reported US$ 1,876 million of UN system expenses aligned to SDG 5 in 2022.

UNICEF is the UN entity responsible for allocating the majority of resources to SDG 6 (65%), through providing children with access to clean water and reliable sanitation and promoting basic hygiene practices.41 Meanwhile, UNDP remains the main implementer of SDG 7 (53%), SDG 15 (40%) and SDG 13 (28%), highlighting how nature, climate and energy formed a large part of UNDP’s 2022 work through its US$ 3.2 billion nature portfolio – the largest in the UN system.42 FAO is the largest implementing entity for SDG 14 (40%) and contributes significantly to the promotion of SDG 15 (29%), in line with the environmental dimensions of agri-food systems, which forms one of the four pillars (‘a better environment’) of FAO’s Strategic Framework. As this implies a healthy planet capable of sustaining agri-food systems that can provide a healthy diet for all is a cornerstone of SDG implementation.43

The WFP, with its mandate to fight world hunger and malnutrition, was the main contributor to SDG 2 in 2022 (85%). SDG 3, for equivalent reasons, is largely implemented by WHO (43%), although UNICEF (22%) and various other UN entities also contribute. Elsewhere, UNICEF allocated half the resources provided to promote education (SDG 4), together with UNRWA (25%), which provides education to young Palestinian refugees.44 Gender inequality continues to exist in both old and new forms, which explains why work aimed at achieving gender equality, particularly in terms of empowering women and girls, cuts across 27 UN entities. Even so, 67% of resources directed towards SDG 5 in 2022 originated from three entities: UNHCR (24%), UN Women (22%) and the UN Secretariat (21%).

SDG 16 and SDG 17 are the goals with the greatest variety of implementing UN entities: 30 and 28 respectively. This underscores the diversity of UN entities providing support to populations in conflict-affected countries and the promotion of peaceful, inclusive societies for sustainable development (in the case of SDG 16), and similarly to strengthening and revitalising global partnerships and international cooperation (in the case of SDG 17).

UN expenditure linked to select SDGs as reported by UN entities, 2022 (US$ million and percentage)

Key insights in a flash

Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB).

Box 2: Reporting perspectives and data sources

- The UN system, which includes all revenue and

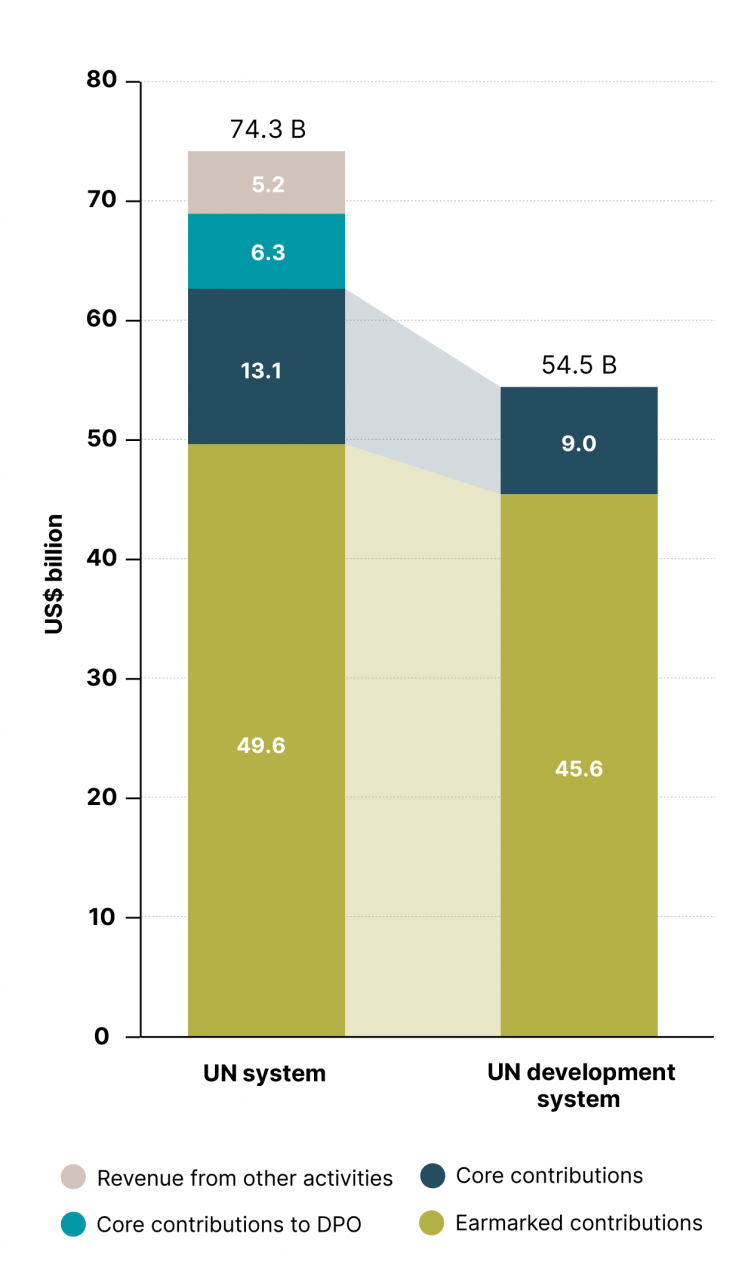

expenditure aggregated from 43 United Nations entities (in some instances with further disaggr tion) reporting to the UN CEB. UN system revenue contributions are channelled through four financing instruments, which are further defined in Box 3: 1) assessed contributions; 2) voluntary core contri- butions (these prior two combined are also referred to as ‘core’); 3) earmarked contributions (which are also referred to as ‘non-core’); and 4) revenue from other activities. Contributions to peace operations are included in the UN system but not in the UN development system – as shown in Figure 35, a sub-stantial part of core funding is dedicated to UN-DPO. - 2) The UN development system (UNDS) encompasses

those UN entities defined as carrying out normative, specialised and operational activities for development to support countries in their efforts to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Contributions to the UNDS consist exclusively of funding for development and humanitarian activities, also referred to together as ‘operational activities for development’ (OAD). These two categories of assistance can be provided as assessed, voluntary core or earmarked funding.

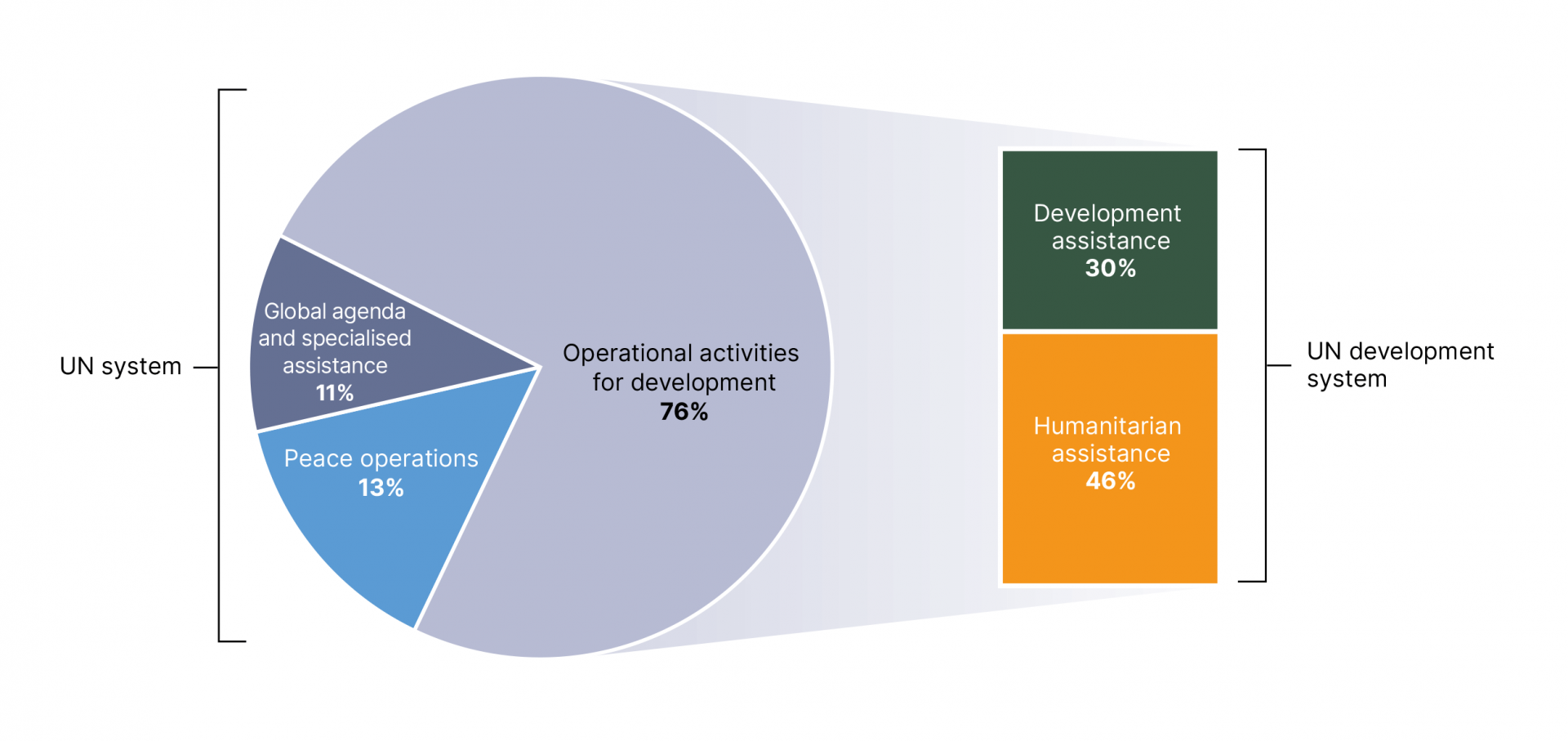

Figure 35 shows which types of expenditure are included in the UN system and UNDS respectively. The UN system has four functions: 1) humanitarian assistance; 2) development assistance; 3) peace operations; and 4) global agenda and specialised assistance. The UNDS supports the first two functions (see Chapter 2).

Contributions to the UN system and UN development system funding, 2022 (US$ billion)

Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB) and Report of the Secretary-General (A/79/72 - E/2024/12).

The data used in the tables and figures in Part One is primarily drawn from the following four sources:

- The UN CEB, which collects and publishes data from the 43 United Nations entities (in some instances with further disaggregation) that have committed to collectively reporting their financial data.

- The UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), which draws on the CEB dataset but only includes data on the UNDS, which constitutes the UN OAD segment. The DESA data is contained in an annex to the Secretary-General’s annual report on implementation of the QCPR process.

- The OECD, which provides data on the sources and uses of official development assistance. It is defined by OECD-DAC as government aid that promotes and specifically targets the economic development and welfare of developing countries.

- The UN Pooled Funds Database, which collects disaggregated data on UN inter-agency pooled funds, provided by UN Administrative Agents of inter-agency pooled funds.

UN system expenditure by function, 2022

Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB).

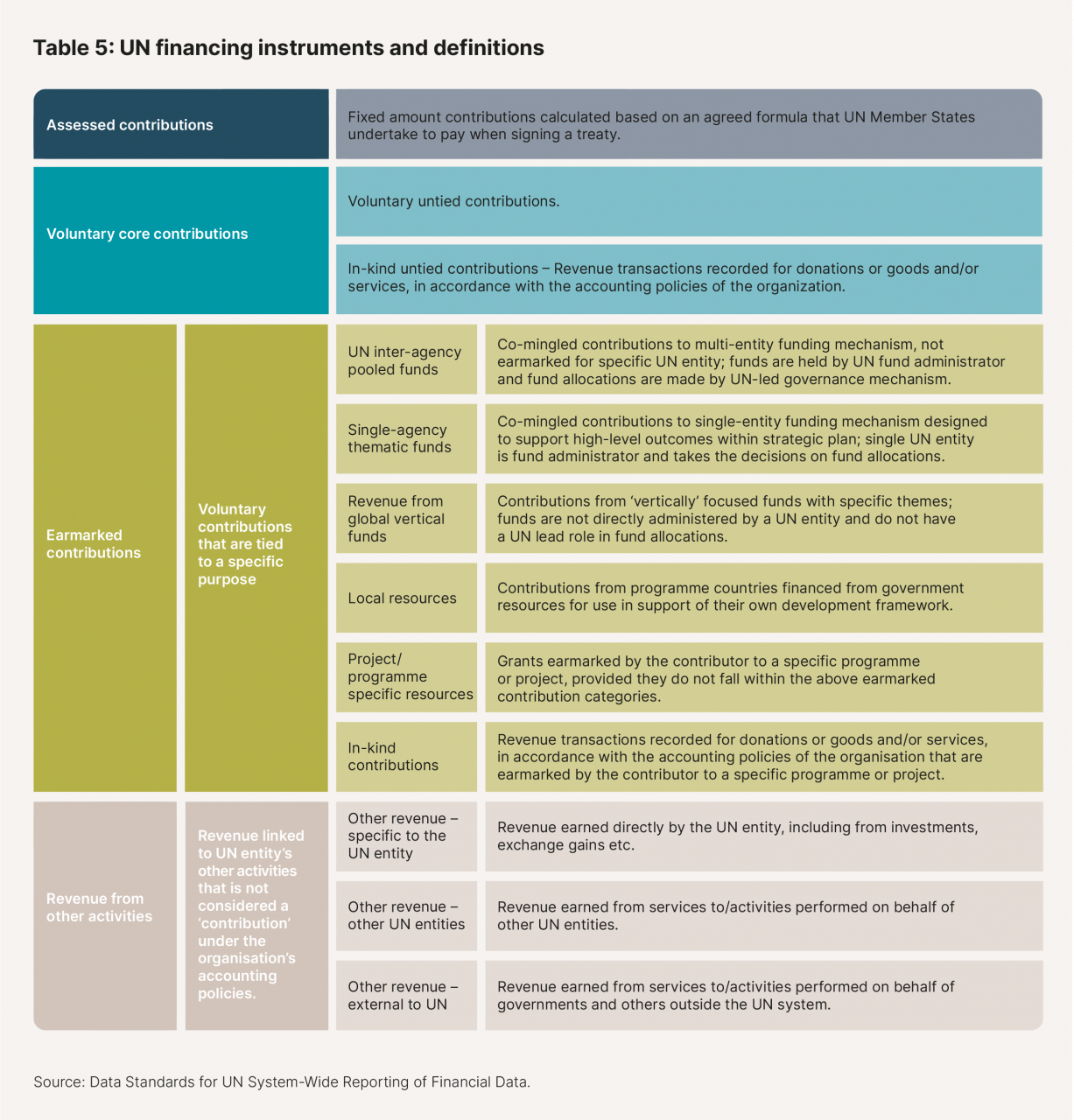

Box 3: The spectrum of UN grant financing instruments

The UN system mainly makes use of four financing instruments, as defined in the UN Data Standards for system-wide financial reporting. The table below sets out the four instruments, their definitions, and the six types of earmarked funding.

Assessed contributions are obligatory payments made by UN Member States to finance the UN regular budget and its peacekeeping operations. They can be thought of as a membership fee. Assessed contributions are based on pre-agreed formulas related to each country’s ‘capacity to pay’. The formula for the regular UN budget is based on GNI, with debt burden adjustments for middle- and low-income countries and adjustments for low per-capita income factored in. The formula for peacekeeping operations also takes account of the fact that the five permanent members of the Security Council (the P5) pay a larger share due to their special responsibility for maintaining international peace and security. These two formulas are adjusted by the UN General Assembly and Member States, normally every three years. Assessed contributions and voluntary core contributions constitute the core funding for UN entities.

Voluntary core contributions, also referred to as regular resources, are funds provided to a specific UN organisation. Core contributions provide resources without restrictions. In other words, they are fully flexible, non-earmarked funds that are not tied to specific themes or locations. They are often used to finance an entity’s core functions in line with its work plans and standards. Voluntary core contributions are, therefore, an important channel of funding, especially for UN entities that do not receive assessed contributions

Earmarked contributions, also referred to as non-core resources, are funds tied to specific projects, themes or locations. While voluntary, such contributions are restricted in terms of how the receiving entity can use them. Earmarked contributions are widely used in the UN system, though the actual extent of earmarking varies. While some funds may be tightly connected to a specific project or programme, others may be part of flexible pooled funds with a thematic or geographical focus. The degree of flexibility may be suitable for different purposes. Strict earmarking and attribution of funding to individual projects may limit results, while soft earmarking to joint pooled funds can enable responses across mandates, help integrate policy, blend financing streams and expand partnerships, thereby increasing impact and improving results. To overcome the steady increase of strict earmarking, Member States and the UN system alike have been pushing for more predictable and flexible UN funding. See Table 5 for an overview of the different instruments for earmarked contributions.

Revenue from other activities covers a variety of income from both state and non-state actors generated through public services, knowledge management and product services. It also includes revenue from investments, exchanges gains and similar sources. Since the 2021 data reporting exercise this revenue can be reported in the following sub-categories: specific to the UN entity, other UN entities, and external to the UN. See Table 5 for the definition of each one of these sub-categories.

In addition to the four financing instruments now used to fund the UN, there are negotiated pledges. Negotiated pledges are legally binding mutual agreements between UN entities and external funders. While not currently a revenue channel for the UN system, they represent a major funding stream for other multilateral organisations. The World Bank, for example, has used negotiated pledges for replenishment of the International Develop-ment Association. One UN entity, IFAD, applies something called negotiated replenishment, which was further described in last year’s edition of this report.

UN financing instruments and definitions

Endnotes

UN, ‘The Sustainable Development Goals Report 2022’, 2022, p. 28, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/.

UNICEF, ‘Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)’, www.unicef.org/wash.

UNDP, ‘United Nations Development Programme Annual Report 2022’, 2023, p. 14–17, https://annualreport. undp.org/2022/assets/Annual-Report-2022.pdf.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO), ‘FAO Strategic Framework 2022–31’, 2021, https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/ 29404c26-c71d-4982-a899-77bdb2937eef/content.

UN Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA), ‘What We Do’, www.unrwa.org/what-we-do/education.

United Nations, ‘Data Strategy of the Secretary-General for Action by Everyone, Everywhere with Insight, Impact and Integrity, 2020–22’, May 2020, www.un.org/en/content/datastrategy/images/pdf/UN_SG_Data-Strategy.pdf.

UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB), ‘Financial Statistics’, https://unsceb.org/financial-statistics.