Rachel Scott heads the Impact team at the Multilateral Performance Network (MOPAN) Secretariat. Her focus is on supporting MOPAN members to use their collective voice – alongside evidence from MOPAN’s assessments – to fulfil their role as responsible shareholders and governors of the multilateral system.1 She specialises in organisations working in crises, and is currently assessing the International Organization for Migration, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the World Food Programme. Rachel Scott joined the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2010 as Senior Humanitarian Advisor, where she reviewed donor practices and led the Crises and Fragility team, which included supporting the International Network on Conflict and Fragility, a Member State network. During this time, she specialised in financing for crises and fragile contexts, and engaged in extensive writing on the topic. Prior to her global policy work, she spent many years in beautiful, fragile contexts around the world, working for the UN and a range of international non-governmental organisations.

The views and interpretations in this article do not necessarily represent the view of the MOPAN Network.

Introduction

United Nations leaders, and hardworking staff on the ground, repeatedly call on donors to reduce earmarked funding, citing inefficiencies, restrictions on how and where to work, slower and more inefficient responses to urgent needs, and situations that are ultimately leaving vulnerable people worse off. But is more flexible funding really the answer? And if financial earmarking really is the root of all evil, then how do we stamp it out? when it appears increasingly fragile at this time of global development disruption and ‘polycrisis’.

We’ve heard about the Cs and the Fs, now it’s time for the Ts

The pressures on the UN system are immense. The COVID-19 pandemic, Conflict and Climate – the ‘three Cs’ – continue to dominate the global landscape. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development estimates that by 2030, 86% of the world’s extreme poor will be living in fragile contexts – numbers calculated before the downstream impact on developing countries of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was fully accounting for.2

In developing countries, it is the ‘three Fs’ that count, with the Food, Fuel and Fertiliser crisis creating devastating impacts around the world – impacts that are already playing out in heart-breaking scenes in the Horn of Africa. A fourth ‘F’ could perhaps be added, namely Financial instability from rising inflation and unsustainable debt levels. If distressed borrowers, particularly in Africa, are to avoid a catastrophic debt problem, the world urgently needs new ideas and rules for debt relief that work for all creditors.3

No one country, organisation or donor can solve these immense challenges alone. Today, the multilateral system, and especially the UN, are needed more than ever. Delivering better solutions to global problems is not just about more money, but also about bringing all parties together, understanding that crises are everyone’s responsibility, and establishing the right norms and standards for prosperity and peace. It is also about ensuring that the right solutions are delivered in the right places at the right time. Only the multilateral system can perform this critical connecting role.

However, recent events have shaken the UN development system to its core: transformational results on critical global issues, such as climate change, have been too slow in being realised; responses to global challenges have often failed to align with local realities; scandals have undermined confidence; and policy issues have increasingly put Member States at odds with global agreements, driving behaviour more in line with national interests than global goals.

In response, support for the UN development system has been scaled back. Countries have failed to align national policy with collective promises on global challenges, leading to reversals on many areas of the Sustainable Development Goals.4 Understanding of the UN development system’s primary purpose is divided: does it act as a convener/facilitator of norms and standards or is it a large-scale service provider? Thus, unsurprisingly, funding modalities have become risk-averse and project-orientated, with donors increasingly using UN organisations as delivery mechanisms to pursue for their bilateral development interests, rather than for the collective good.

That is why now is time to talk about how the ‘three Ts’ – Trustworthiness, Trust and Together – can deliver a reinvigorated global system, with a key connecting role for the UN. A system where all stakeholders can join forces around global challenges and to leave no one behind. Doing this will require three things: 1) a return to real multilateralism working together; 2) actively building trust across the system and with key stakeholders, including funders; and 3) supporting institutions to become more trustworthy.

Towards trustworthy

We have all heard the rhetoric, ‘if you give us more money, and more flexible money, we will be able to deliver better results’. But is earmarking really the problem? Earmarked funding is often blamed as the root of all evil, but statistics show that core funding to the UN development system has remained stable over the past decade (Figure 1), although the ratio of core vs earmarking does vary significantly across UN organisations (Figure 2). Risk-averse board members, and increasingly complex administrative and reporting requirements, are perhaps more to blame.

So, if earmarking is not the problem, what is? We can all agree that, to fulfil its potential, the UN development system must not only perform well, but must be governed effectively and transparently, and have the right resources. Underneath all of this lies one thing: trust. And yet, building trust must start with UN organisations becoming trustworthy – it is all interconnected.

The Multilateral Performance Network (MOPAN) was set up 20 years ago to foster trust by ensuring that the multi lateral system provides a good ‘return on investment’ – in other words, to see whether organisations receiving funding are relevant, fit-for-purpose and delivering results (Box 1). A total of 36 organisations have been assessed over the past 20 years – UN agencies, funds and programmes; development banks and international financial institutions; and vertical funds – with many evaluated assessed (these are not evaluations) several times.

What do MOPAN assessments tell us about the measures that need to be put in place to ensure a trustworthy multilateral system? Some things are obvious. Organisations must have the right strategic direction; be set up to deliver results, including in the most difficult places; have a stable governance and financial environment to run its operations; have the right – and equal – partnerships; and deliver evidence-based solutions and results.

Ensuring that integrity and ethical safeguards are in place is core to a relationship based on trust. MOPAN assesses the ability and performance of organisations in preventing and addressing fraud, corruption and misconduct. On top of this, MOPAN’s remit was further expanded in 2020 with the introduction of dedicated performance benchmarks on the prevention of sexual exploitation and abuse and sexual harassment in all assessments. Clearly, there can be no trust in an organisation that tolerates any form of sexual misconduct, and thus combatting this bad behaviour has become a priority area for members of the UN.

Recent discussions amongst MOPAN members point to some emerging principles that can refresh the debate on trustworthiness. These include:

- Purpose, priorities and strategy: UN organisations must deliver sustainable, inclusive change at scale, but this is not enough. They must also work together and connect across the system – trust each other – to tackle fragmentation and tailor solutions to local realities.

- Governance and structure: The UN development system must clearly listen to, and action, the priorities of all Member States – this requires robust governance structures, alongside clear oversight measures and accountability to all stakeholders.

- People, systems and processes: UN organisations must work efficiently, but must also have the right leadership, eliminate toxic working environments, focus on cost effectiveness, and work in real partnership – including partnerships that are already strong before crises hit.

- Enablers and safeguards: UN development organisations must always demonstrate the highest ethical standards – from fraud and corruption to sexual misconduct and beyond – and be open about failures and shortcomings.

- Results: It is not enough to just be results-focused. Instead, the UN development system must achieve the right results, especially for the most vulnerable, striking the right balance between global public goods and localised solutions.

Organisations can always do better, and a common agreement on benchmarks will tell us when performance is good enough, when the bar is met and thus to what extent an organisation can be considered trustworthy. And, of course, once organisations are trustworthy, we can set about building trust.

Box 1: What is MOPAN?

The Multilateral Performance Network (MOPAN) is an independent network of 22 Member States who work together, as responsible shareholders and funders, to improve the performance of the multilateral system, making it stronger, better and smarter. Set up in 2002, MOPAN members today invest over US$ 70 billion to and through the multi-lateral system every year. MOPAN assessments cover the strategic, operational, relationship/partner - ship and knowledge management aspects of selected multilateral organisations, as well as their results at the global, regional and country level.

Source: www.mopanonline.org

Earning trust, earning autonomy

Trust is precious: it takes years to build, seconds to break, and forever to repair. What does trust look like? Trust means confidence in the global agreements and institutions that make up the UN development system – when people, including donors, believe that the system reflects their values, is under their control, and works with integrity, fairness and openness for the benefit of everyone. Trust means continuously demonstrating that there are reasons to work together for the global good. And there must be public trust – because most resources for the UN system come from taxpayer funds, and most UN programmes affect people’s lives.

Trust is also about earned autonomy, with UN development system leaders earning the right to autonomy through consistently demonstrating the trustworthiness of their organisations. In practice, this means Member State engagement in governance processes, strategic direction-setting and oversight, in return for handing over the responsibility to deliver – letting organisations decide how to programme, how they spend their budgets, and what their staff should be paid. Of course, all this requires less earmarked funding. So, first trustworthiness, then trust, and finally together.

Real multilateralism is about working together

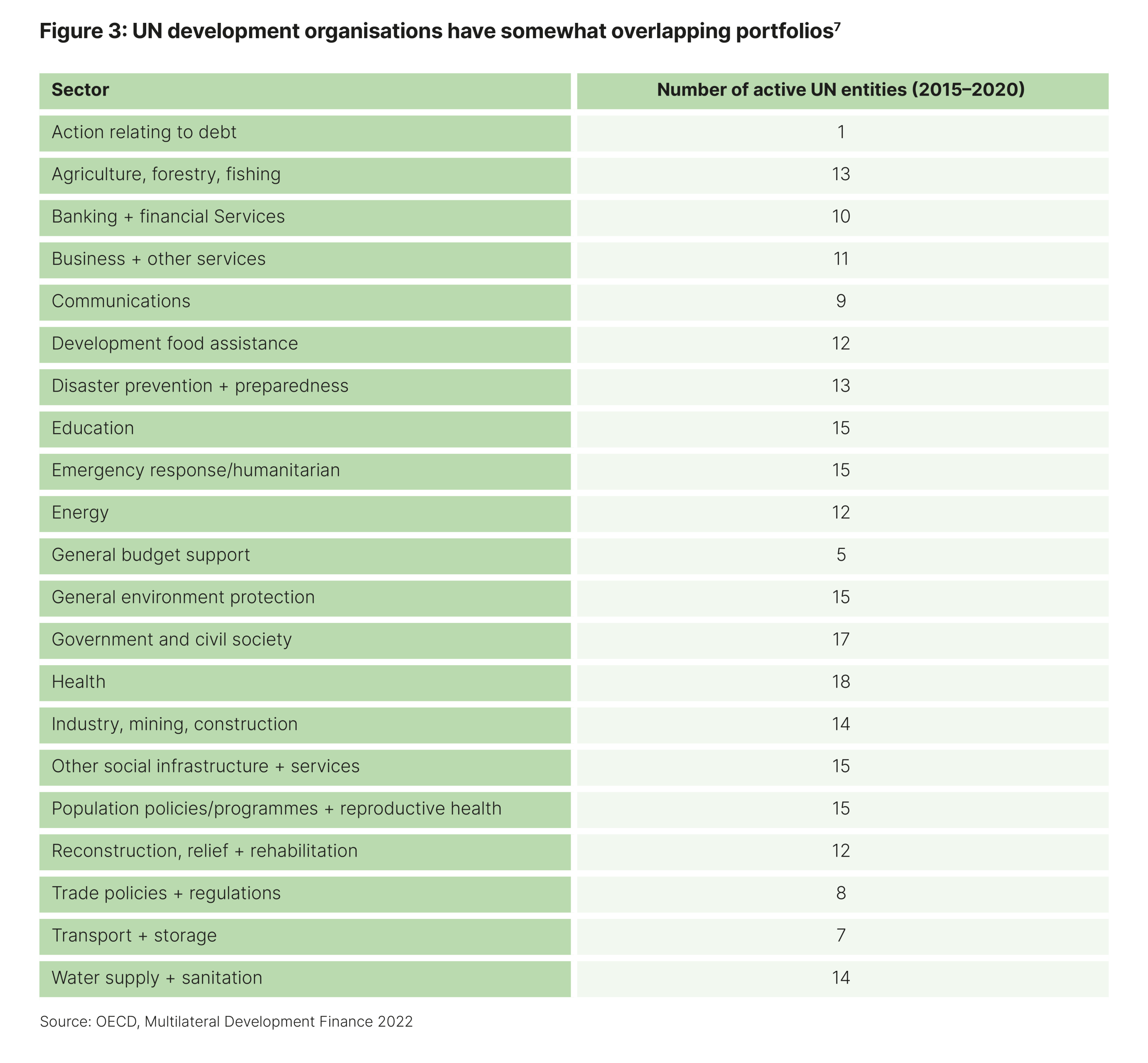

Multilateralism is about connecting parties, working together, delivering global solutions to global challenges. That is why we talk about the UN development system and not a set of UN organisations. And yet, the UN development system architecture is becoming ever more complex and fragmented (Figure 3).

Ensuring that this crowded, complex and fragmented UN development system works together, and is fit-for-purpose for the challenges of today and tomorrow, will require effort from all sides.

The first efforts must come from Member States. As responsible members, shareholders and governors, they need to provide the right incentives for the system to work together – and ensure that funding for their individual areas of interest does not lead to increased fragmentation. These efforts must be complemented by multilateral leaders – learn to trust others across the system, actively contribute to and resource co-ordination mechanisms, and deliver coherent responses to global challenges.

More money is not the only answer

In conclusion, more money is not necessarily the only answer, nor is more flexible money going to magically appear to magically solve the UN development system’s problems. In today’s demanding environment – challenged by the Cs and Fs – the UN development system must focus on the Ts: becoming more trustworthy, earning trust and working together. Only then can it earn autonomy and build the case for the right resources, working together for the right solutions to pressing global challenges.

Endnotes

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), States of Fragility 2020 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1787/ba7c22e7-en.

Rebeca Grynspan, ‘The world lacks an effective global system to deal with debt’, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2 February 2023, https://unctad.org/news/blog-world-lacks-effective-global-system-deal-d… the%20public%20debt%20of,the%20 situation%20is%20deteriorating%20rapidly.

UN, ‘The Sustainable Development Goals

Report 2022’, 2022, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/.