Nada Al-Nashif was appointed United Nations Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights effective February 2020 and has over 30 years of experience within the UN as an economist and development practitioner. Previously, she served as Assistant Director-General for Social and Human Sciences at UNESCO (Paris), as Assistant Director-General and Regional Director of the International Labour Organization’s Regional Office for Arab States (Beirut), and at the UN Development Programme in various headquarters (New York) and field assignments. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Philosophy, Politics and Economics from Balliol, Oxford University, and a Master’s degree in Public Policy from the John F. Kennedy School, Harvard University.

The views and interpretations in this article do not necessarily represent the view of the United Nations.

Introduction

Seventy-five years ago, amid the barely cooled embers of the Second World War, states signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), a unique document which articulated a clear global commitment: never again. The UDHR was nothing short of miraculous in its recognition that human rights were the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world; universal, indivisible and fundamental across every divide – religious, cultural, geographic, environmental. Yet today, shocking disparities and global crises have destabilised this foundation.

Overcoming challenges in a polarised world

The world is in an alarming state as people endure deepening inequalities, devastating natural disasters, a shrinking civic space, social unrest fuelled by hate speech, and an erosion of democracy. The pushback on human rights, combined with social unrest and conflicts in many parts of the world, have undermined the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

We may be seeing it in the rear-view mirror, but the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic are still with us. It reversed economic gains, leading to the first rise in extreme poverty in two decades and highlighting profound fragilities created by a human rights deficit.1

Attempts to politicise the human rights agenda reflect increasingly polarised positions, weakening our human rights foundation in a way that erodes consensus, multilate-ralism and international solidarity. Some leaders have capitalised on this turbulence to close off avenues to dissent, giving rise to popular disillusionment and mistrust in democracy and its institutions. Even in the most advanced democracies, there is a burgeoning belief that political systems need a major overhaul, if not outright reform. Rights we once thought of as entrenched are being chipped away.

Yet all is not bleak. In counterpoint to this erosion are massive human rights gains in the decades since the UDHR was signed: many people live longer, better, healthier lives, their rights protected by robust, life-saving, cross-pillar interventions from UN-led humanitarian responses to peace and security agreements, as well as investments in sustainable development.

The social movements active around the world – Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, the Iran protests – are all rooted in the same values of equality, dignity and justice. When young people take to the streets, they speak the language of human rights, confirming the relevance of these rights as a unifying force.

It is against this conflicted backdrop of turmoil and hope that the High Commissioner for Human Rights launched the Human Rights 75 Initiative, calling for a rejuvenation of the spirit that led to the UDHR’s adoption 75 years ago.2 In his words, it is time to ‘rekindle the flame of human rights’ and reposition these rights where they belong: in state action, and at the heart of both the UN’s work and of every single person they represent.

This 75th anniversary year – which also marks the 30th anniversary of the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action – is our chance to reconstitute the original consensus around human rights and build on the solid achievements since then. Collectively, we can do this by promoting the universality and indivisibility of human rights, looking to the future, and bolstering the human rights ecosystem.3

Promoting the universality and indivisibility of human rights

Perhaps one of the human rights system’s greatest challenges is to ensure timely attention to all issues and protect the rights of all. Delivering on universality and indivisibility – principles that lie at the core of the UDHR – requires dealing meaningfully with all violations that arise as part of emerging or protracted patterns, whether they make headlines, or whether they deal with discrimination, debt or international financial reform, because an affront to one person’s dignity is an affront to human dignity.

Civil and political rights are fundamental, as are economic, social and cultural rights. Interconnected and interdep-endent, these rights build upon one another to provide the basis for peace and development. Where there is ethnic discrimination, conflict or mass displacement may follow. One cannot enjoy basic freedoms of health or education without the right to protest when expectations are not met or where due process is absent. Breaking down the artificial silos that would isolate one set of rights from another is imperative if we are to forge a renewed consensus around the UDHR. As Article 2 sets out, ‘Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind’.

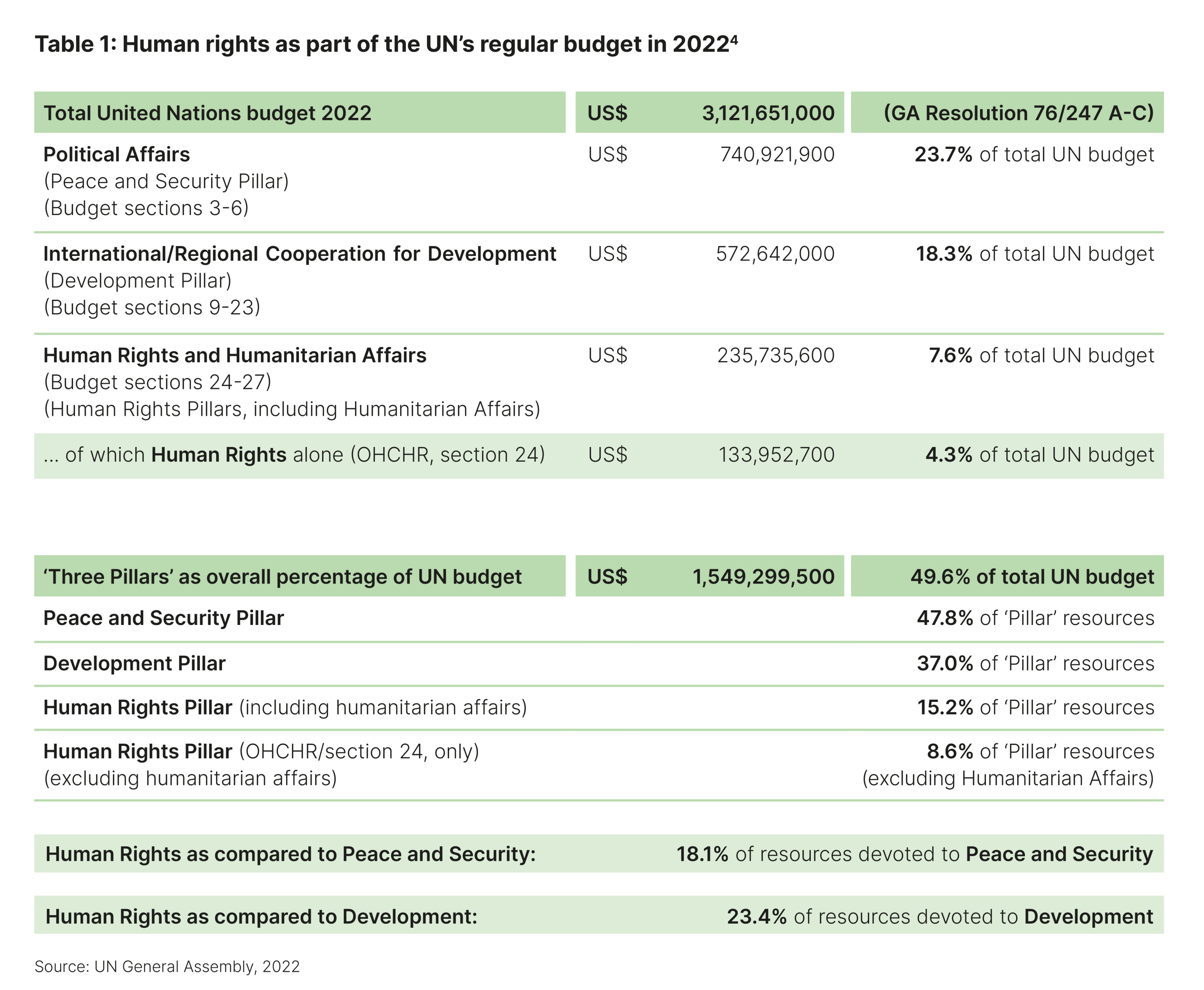

While the COVID-19 pandemic and multiple other crises continually demonstrated the importance of human rights, the investment has failed to materialise. The work of human rights at the UN remains chronically underfunded: with slightly over 4% of the UN regular budget, it is the least financed of the three UN pillars (human rights; peace and security; development – see Table 1). At the same time, the mandates established by the Human Rights Council constantly rise. Between 2015 and 2022, the resource requirements increased from US$ 15 million to just over US$ 44 million (Figure 1).

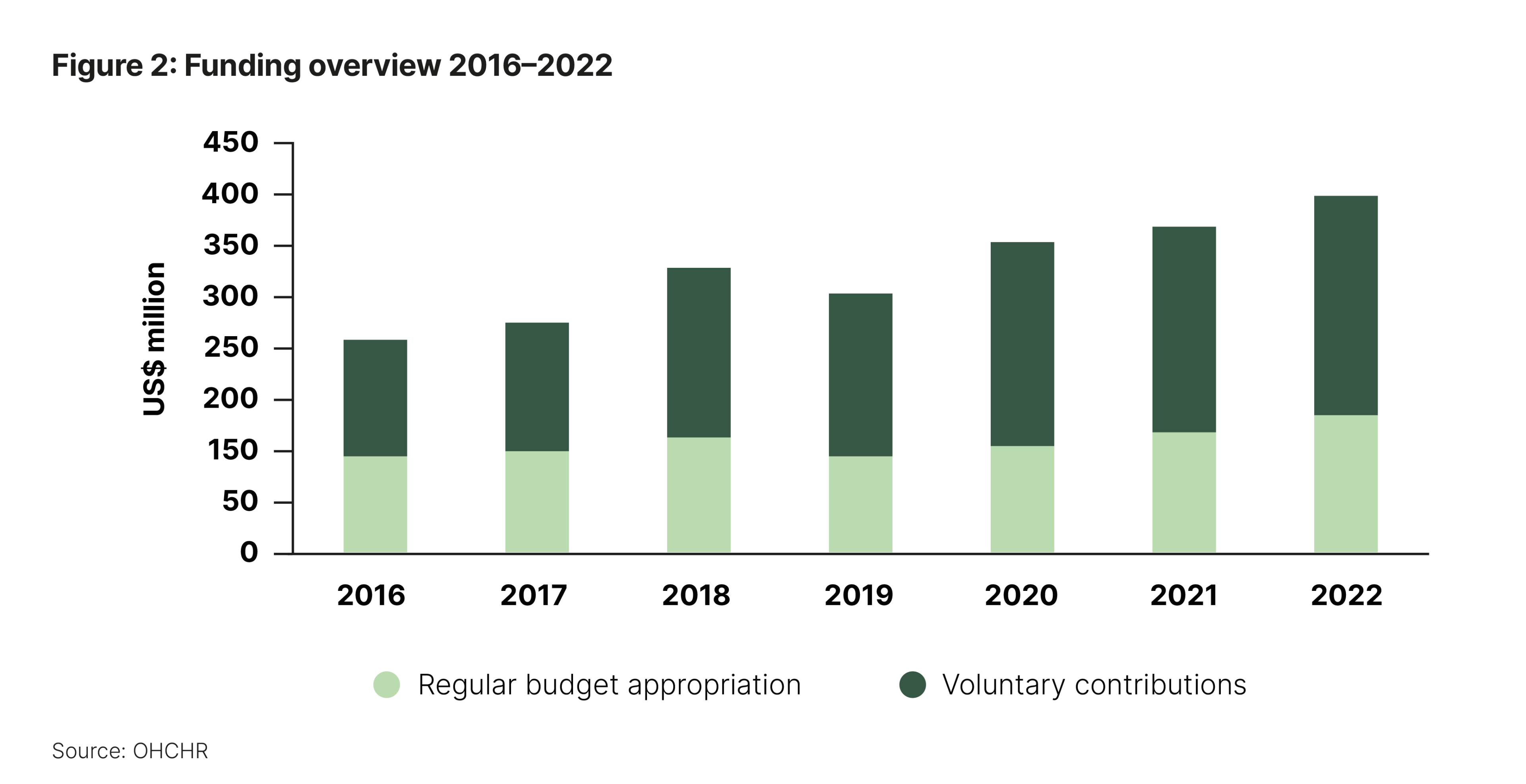

This underfinancing is stark within the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), which depends far too much on the unpredictable voluntary contributions that fund 61% of its work. Further weakening this financial edifice is earmarking, which raises transaction costs, and limited funding diversification, which ties our hands when more, not less, flexibility is required in support of the progr-ammatic agility to protect those most vulnerable and at risk.

To effectively do this work and meet this promise, support for human rights-based solutions is fundamental, requiring both adequate financial resources and the political will to recommit to the normative agenda of human rights.

Looking to the future

The next 25 years will be crucial. Global concerns at times appear to threaten our very survival. To plan for the next quarter century will involve listening to diverse voices, including youth, and demonstrating a willingness to adapt, while learning the lessons of the past: that robust systems grounded in human rights of all are crucial if we are to weather future crises.

We have the evidence before us: policies and measures anchored in human rights protect people better over time. States that embraced innovative social protection measures during the COVID-19 pandemic proved more resilient, while strong fiscal policy measures in some high-income countries made all the difference in reducing COVID-19’s impact on poverty.

With the world changing faster than we can keep up, we have reached a tipping point that demands updated thinking, backed by innovative tools and methodologies. The frighteningly rapid spread of new technologies is a case in point. Artificial intelligence is evolving so quickly its very creators are demanding a halt. While these technologies have tremendous potential for good, they may equally imperil human rights. They are failing to protect. Social media can help propagate disinformation and hate speech, while illicit spyware can undermine privacy and personal security, as we saw when the Pegasus hacking device was used to clamp down on journalistic and political dissent.5

As technology snowballs, we stand on the edge of irreversible climate change, which jeopardises human rights and delivers a disproportionate environmental impact on the most marginalised and disadvantaged. Yet there is a failure to protect populations from these dangers or provide them with the tools to adapt to rapid change, as we sadly note each time there is a climate incident.

Tackling these catastrophes is of the utmost urgency: consider that a single event, the devastating 2022 floods in Pakistan, affected more than 30 million people and will take years to overcome. In 2023, US$ 52.9 billion is needed to provide humanitarian assistance to 230 million people across over 40 countries and territories, as reflected in UN humanitarian response plans. So far, US$5.3 billion has been provided.

Confronting these and other emerging issues will require concerted efforts not only by the various UN entities but by all stakeholders to build awareness of human rights, integrate them into policies and processes, ensure accountability, and involve all those affected. While coping with evolving crises is a pillar of our work, a cornerstone of our forward-thinking approach must involve greater use of human rights as a prevention tool. Human rights can help us identify grievances before they turn into confrontations that undermine peace and development, saving lives in the process. In Syria, the UN requires US$ 4.44 billion to provide the 15 million people in need with humanitarian assistance (out of a population of 22 million).

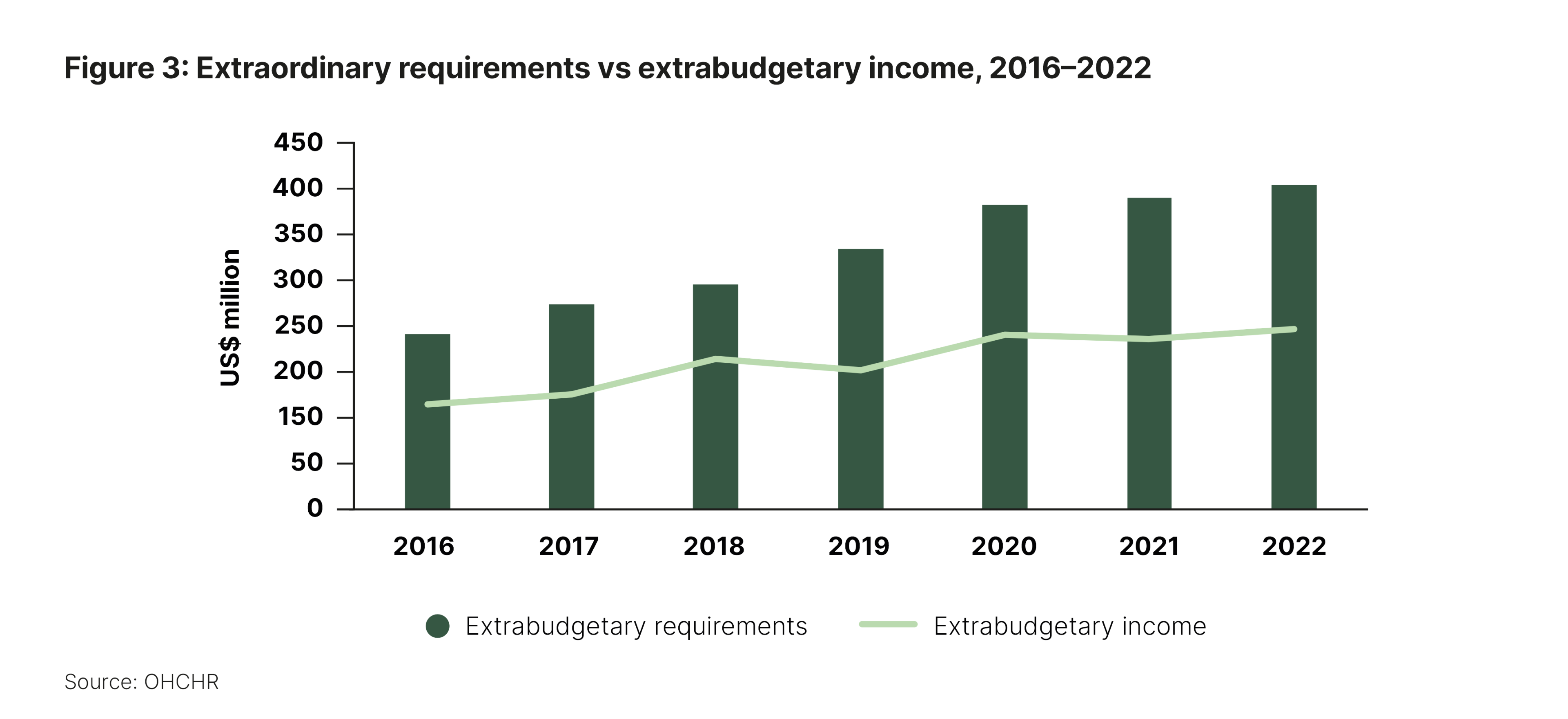

In turn, OHCHR’s Office for Syria, which works with a budget of US$ 4 million, struggles to receive adequate funding although its early warning analysis could have enhanced prevention. In 2023, the Myanmar Humanitarian Response Plan request US$ 764 million to reach 4.5 million people prioritised for life-saving humanitarian support (out of 17.6 million people in need). Despite its modest annual budget requirements set at US$ 2.67 million, OHCHR’s Myanmar Monitoring Team functions at half capacity, based on voluntary contributions from donors.

This is why OHCHR deployed Emergency Response Teams (ERTs) to seven of our regional offices. By identifying trends and assessing risks, ERTs are helping promote both situational awareness and early warning, feeding into larger UN prevention efforts. OHCHR’s work during the 2022 Kenya elections underlines the case for prevention. As part of a broader UN engagement, we fostered efforts to hold peaceful elections by countering online hate speech, supporting sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) prevention and response, and engaging in civic education. As voting drew near, we deployed a multi-disciplinary OHCHR team and UN Standing Police Capacity officers, contributing to an overall peaceful outcome that saw far fewer human rights violations and less electoral-related SGBV than during the 2017 elections.

In October 2021, the Human Rights Council rejected the renewal of the Group of Eminent Experts on Yemen mandated to monitor human rights violations and other atrocities committed by all parties to the conflict. The number of civilians killed or injured has almost doubled since, a testament to the preventive power of human rights monitoring.6 Moreover, OHCHR’s presence in Yemen remains chronically underfunded, its critical monitoring operations at risk as a result. In the words of Benjamin Franklin, ‘an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure’.

Bolstering the human rights ecosystem

A robust human rights ecosystem is a prerequisite for dealing effectively with the pressures. We already have a remarkable human rights infrastructure, but it needs to be bolstered and truly fit for purpose.

In his 2020 Call to Action for Human Rights, the UN Secretary-General recognised the centrality of human rights to the UN’s mandate. While OHCHR provides an anchor for human rights within the UN, these rights are already intrinsic to all aspects of the UN’s work. They are the basis for many protection actions, are integrated into peacekeeping operations and protecting the fundamental rights of people in crises. In development, positioning Human Rights Advisers in 51 UN country teams has been instrumental in promoting human rights-based approaches and delivering results. Through our ‘Surge Initiative’, which includes economists and development specialists, we have stepped up our technical advice to states to advance human rights-based strategies.

Proliferating conflicts, increasing polarisation, growing mistrust in institutions, democratic setbacks – all these have inevitably increased demands on OHCHR Office. While this confirms the importance of our work, it also highlights the gap between mandates and resources.

We remain in a financial straightjacket, making it urgent to strengthen synergies across UN pillars and engage in partnerships across the UN and beyond. The challenges are global and no single entity can address them alone. Partnerships, which are at the core of SDG 17, are essential to implementing the 2030 Agenda and finding innovative solutions to the risks faced by human rights and the environment. These partnerships allow us to access new resources and expertise, increase our visibility and credibility, network to expand our reach, and explore new opportunities for growth and expansion.

An historic opportunity

For human rights to remain at the heart of the UN’s response compels us to engage in forward thinking and tread new ground. We require a global recommitment to human rights, a sustained effort that strengthens these rights and the institutions that frame them, backed by multiyear funding to meet escalating demands and expectations.

This is an important year for human rights, we are once again seeking to re-establish harmony beyond discord. To achieve this, everyone needs to step up, walk the talk and commit to bolstering the human rights architecture, actioned through robust partnerships, mobilising financial, moral and political support. We did it after the Second World War and we cannot afford the alternative.

Endnotes

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, ‘End poverty in all its forms everywhere’, https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2022/goal-01 accessed online on 28 July 2023.

See the Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna on 25 June 1993, http://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/vienna-decla….

Sources: UN General Assembly Resolution 76/247 A-C, ‘Programme budget for 2022’, 6 January 2022, https://undocs.org/A/RES/76/247; and UN General Assembly, ‘Proposed programme budget for 2023’, A/77/6 (Sect. 24), Table 24.35, 27 April 2022, p. 77.

Pegasus is a spyware from NSO Group that targets iMessage and can hack iPhones of specific targets using a zero-day attack. It was discovered in August 2016 after a failed installation attempt on the iPhone of a human rights activist led to an investigation revealing details about the spyware, its abilities, and the security vulnerabilities it exploited.

Norwegian Refugee Council, ‘Yemen: Civilian casualties double since end of human rights monitoring’, 10 February 2022, http://www.nrc.no/news/2022/february/yemen-civilian-casualties-double-s… the%20four%20months%20before,the%20 Civilian%20Impact%20Monitoring%20Project.