John Hendra provides strategic advice on multilateral effectiveness/reform, development financing, leadership and gender equality through his consultancy practice. He served the United Nations for 32 years, most recently as UN Assistant Secretary-General (ASG), helping prepare the UN Secretary-General’s two seminal UN Development System (UNDS) reform reports and substantively supporting intergovernmental negotiations which led to the UN General Assembly’s reform of

the UNDS. Other roles included serving as UN ASG and Deputy Executive Director at UN Women, as UN Resident Coordinator and UNDP Resident Representative in Vietnam, Tanzania and Latvia and as the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Director for Resource Mobilization. In his consulting capacity he serves as a part-time Senior Advisor to the Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation.

Introduction

Today our world continues to suffer multiple crises stemming from wars in Ukraine and Gaza, concomitant cost-of-living, food and fuel crises, an uneven recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, a debt crisis for many countries in the Global South and a burning climate crisis, to name a few. While the 2030 Agenda remains the roadmap going forward, there is no doubt that the world must scale up significantly to get back on a path to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The United Nations Development System (UNDS) has a key role to play in helping galvanise governments to achieve the SDGs by moving from funding to helping leverage much larger development financing for national SDG priorities. However, the UNDS needs sufficient and predictable quality funding to be able to play this role while also fulfilling its specific multilateral mandate. Instead, development funding to the UN is at risk of being further cut – if not severely squeezed – just at this critical time when it is needed most; what’s more, it continues to be provided in a heavily earmarked manner that inhibits the more strategic and collaborative responses required.1

With increased polarisation and possible radical electoral shifts in top contributing governments there is significant uncertainty. Already there are serious storm clouds on the immediate horizon as the three top donors to the UNDS – the United States (US); Germany; and the United Kingdom (UK) – are reducing their Official Development Assistance (ODA) quite significantly in 2024. On top of that there is need for a major International Development Association (IDA) replenishment this year amidst a traffic jam of other multilateral funds from Gavi (the vaccine alliance) to new entities like the Loss and Damage fund also seeking replenishment. With the multilateral system under unprecedented strain, it becomes even more critical to incentivise much greater complementarity, coordination and consolidation across the system and its various key functions.

Preliminary 2023 ODA Figures

Preliminary ODA figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), released in April 2024, show that a record US$ 223.7 billion was provided in 2023, a 1.8% increase from the US$ 211 billion provided in 2022.2 The largest providers again by volume were the United States, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and France. For the second straight year, Ukraine received the most ODA, rising 9% in 2023 to reach US$ 20 billion, including US$ 3.2 billion in humanitarian aid. ODA also increased to the West Bank and Gaza in 2023 with estimates showing a 12% increase from 2022 to US$ 1.4 billion with just half of that being humanitarian aid. Globally, humanitarian assistance from ODA allocations rose by 4.8% in 2023 to US$ 25.9 billion.3 Despite these increases, the amount that’s been allocated for multilateral organisations overall including the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and health funds such as Gavi, has only increased slightly overall, and even shrank twice in the past six years.4

Importantly, ODA to least developed countries (LDCs) and Sub-Saharan Africa increased by 3% and 5% respectively from 2022 and was helped by the 6.2% fall in share of ODA that Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members spend domestically on hosting of asylum seekers – although the amount spent was the same, US$ 31 billion or 13% of ODA.5 Carsten Staur, the DAC chair, said that while there had been a bounce back in aid to LDCs and sub-Saharan Africa it was ‘not enough…given the challenges many of our partner countries are facing, stemming from climate change, from the long-term effects of COVID, from the war in Ukraine and all the knock-on effects of these crises, we’re falling short’.6

Many activists went further; as Matthew Simonds, senior policy officer at the European Network on Debt and Development said: ‘Even though wealthy countries reported spending more money on overseas aid, the devil is in the detail. A closer look reveals that yet again, geopolitical priorities and domestic budgets have taken precedence over the needs of the world’s poorest people’.7

Whither quality UNDS funding in the near term?

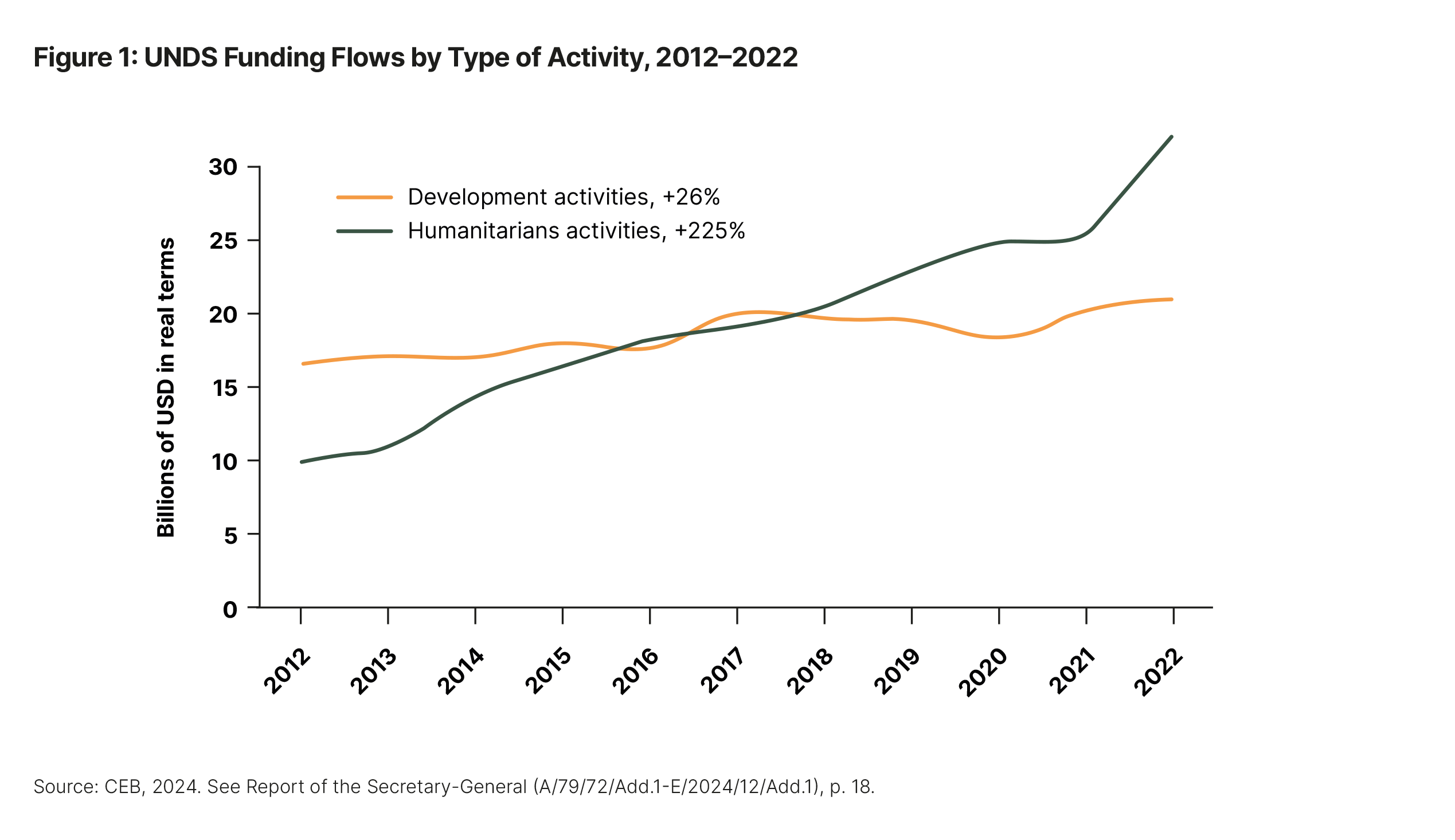

While ODA figures in the aggregate are perhaps more encouraging than some observers thought they’d be even excluding still very high levels of domestic support for asylum seekers, a more detailed analysis later below reveals some underlying challenges. In a similar vein, total final funding figures to the United Nations operational activities for development for 2022 were also recently released and they amounted to US$ 54.5 billion in 2022, representing an impressive increase of 17% compared to 2021.8 That said, as shown in Figure 1, this increase was almost entirely humanitarian funding as the past year has been characterised by crises and violence in various parts of the globe. Conflicts are responsible for most of the world’s humanitarian needs; nearly 300 million people are estimated to require humanitarian assistance and protection this year.9

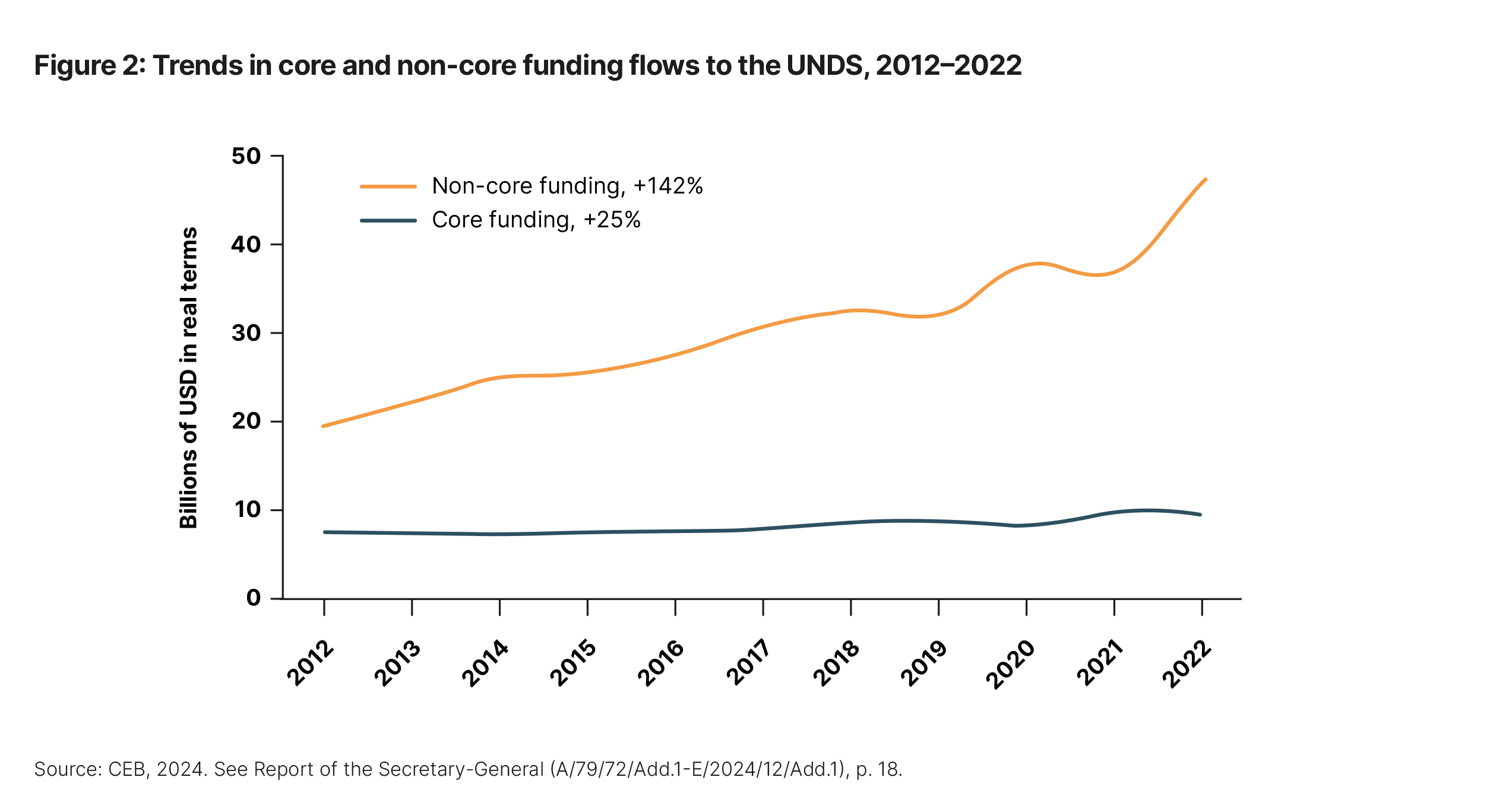

When one scratches the surface, 2022 was a setback for more quality UN development funding with core funding for development-related activities dropping to 18.3% from 21.4% in 2022, significantly below the target of 30% set in the 2019 Funding Compact. Excluding assessed contributions, core funding accounted for only 12% of total voluntary funding in 2022, the lowest share ever, which poses a real threat to the effectiveness of United Nations development work.10 Feedback from governments also shows that projects financed by core resources are more likely to be closely aligned to their national needs and priorities.

As shown in Figure 2 below, the growth in core resources to the UNDS has ostensibly flatlined over the past decade while growth in non-core resources has increased by almost 150%. The best way to reduce crises remains addressing their root causes and underlying inequalities which is the focus of much of UN core resources. Investing in sustainable development is critical for prevention and exit out of crises thereby enabling more resilient recovery; and these efforts must be supported and incentivised by funds which enable delivery in a coherent, complementary and strategic manner.

Other key aspects for enhancing the quality of UN development funding also saw setbacks in 2022. In 2021, 12.3 % of all non-core funding to development activities was channelled through inter-agency pooled funds, surpassing the funding compact target of 10%. However, in 2022 contributions to inter-agency development pooled funds declined by 22%, accounting for 8.9% of total non-core funding for development.11 Multi-year financial commitments are another effective method of providing funding with flexibility and predictability; they also help entities be more strategic through longer-term programme and resource planning while dealing with negative impacts of income fluctuations. Here, too, 2022 figures show a general trend of decreasing proportion of voluntary core funds that are part of multi-year commitments to the lowest level in five years.12

In short, the latest Quadrennial Comprehensive Policy Review (QCPR) report by the UN Secretary-General shows that attracting high quality funding is increasingly a major challenge for the United Nations development system. A new and ambitious Funding Compact has just been developed that is less technical and more strategic as discussed in more detail below. It will be critical that this new Funding Compact resonates with senior decisionmakers and facilitates much greater political will, as well as buy-in at the country level. Addressing the worsening imbalance between core and non-core resources remains a particular priority.

Three major reasons for increased concern

Unfortunately, further analysis of ODA projections, continued pressure on many OECD/DAC countries regarding support to Ukraine, and the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), and a year rife with replenishments to major multilateral funds and institutions means that this challenging quality funding situation facing the UNDS will likely become substantially worse before it gets better.

First, reductions: Decline of the top donors to the UN

Upon closer inspection of 2023 ODA figures, it becomes clear that G-7 countries continue to dominate ODA with US$ 170.9 billion, or 76% of total ODA in 2023, coming from the G-7 with US$ 52.8 billion coming from all the rest.13

Looking forward, two things should be of considerable concern to the UNDS. First, that four of the top overall providers of ODA – USA; Germany; UK and France – all have announced significant reductions for 2024, and in some cases, 2025 as well. Second, that the top three government contributors alone – again USA; Germany; and the UK – accounted for a staggering 42% of total funding to the UNDS in 2022.

In the case of the USA, the largest contributor to ODA and UN development activities, it finally passed its long-delayed 2024 budget (fiscal year 2024 runs from October, 2023 through to September, 2024) which includes a nearly 6% cut in foreign affairs funding.14 Overall, it appears that major increases to humanitarian assistance and refugee support, while much needed, will come at the cost of development. While the US will meet its regular UN budget obligations at the assessed rate of 22% along with funding of UN Specialised Agencies, core funding to UN Funds and Programmes at US$ 437 million is being reduced by almost 17% from the previous year. While such a drop will have real implications on UN development work, the fractitious legislative backdrop potentially portends a significantly bleaker future in this election year as the starting point was a House of Representatives bill with zero funds for the UN regular budget, zero voluntary contributions towards core funding and a small amount for UN peacekeeping.15

Germany, traditionally the second largest donor to the UN, is also sharply reducing its ODA. In 2023, the development budget was cut by € 1.7 billion while the humanitarian budget was trimmed by € 430 million when compared to 2022. The revised budget for 2024 went further reducing the foreign development budget by nearly another € 1 billion (US$ 1.08 billion) while the humanitarian budget was cut another nearly € 500 million.16 Recent leaked German Finance Ministry forecasts show a further planned reduction of € 400 million to the development budget in 2025, sparking outrage both within the Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) and amongst development and humanitarian organisations while risking violating the coalition government’s agreement that Germany provides at least 0.7% ODA/gross national income (GNI).17

Despite previous indications to the contrary, the United Kingdom is diverting GB £ 3.2 billion (US$ 4.1 billion) from its aid budget to pay the hotel bills of asylum seekers – a 600 million GBP year-on-year increase from last year when 29% of the aid budget was spent on domestic in-donor refugee costs.18 The OECD called on the UK to cap its domestic spending of aid in a very critical report in early March, 2023.19 Meanwhile, France, the fourth largest provider of aid, has also recently slashed its ODA budget by 12.5% or € 742 million (approximately US$ 805.9 million).20

Regarding the rest of the G7, Japan, the third highest contributor to ODA in 2023 after increasing its ODA by almost 16% for both bilateral and multilateral contributions, will likely not see any increase in 2024.21 Canada should see a slight increase to just over CAN$ 7 billion for fiscal year 2024/2025 thanks to an increased CAN$ 350 million in humanitarian funding over the next two years.22 That said, last year Canada allocated CAN$ 6.9 billion, down 15% from 2022 ODA levels, so the increase is marginal. Italy’s budget documents indicate that the country would spend € 6.3 billion (US$ 6.6 billion) on ODA in 2024, a slight increase from 2023.23

Some other non-G-7 donors have also been cutting aid and radically changing long-held policies. The new Dutch Government recently released its coalition agreement which states that the current development budget will be reduced by two-thirds over 2025-2027 with € 350 million cut in 2025, increasing to € 350 million in 2026, and reaching € 2.5 billion annually from 2027. In 2022, The Netherlands was the sixth highest donor to the UNDS.

This past March Sweden announced a major change in development policy terminating all agreements to deliver aid through 17 Swedish NGOs as strategic partners and also opening up competition for contracts to NGOs from outside Sweden.24 The Swedish government has taken other measures affecting development assistance since coming to power in late 2022 including ending the long-time commitment to spending 1% GNI on Swedish development assistance and reducing the portion of its assistance going to the UN and its agencies and rechannelling it instead as bilateral aid through Sida.25

Second, reallocations: A tale of two targets

While a fifth DAC member achieved the UN target to spend 0.7% of GNI on aid – with Denmark joining Norway, Luxembourg, Sweden, and currently Germany – preliminary 2023 figures for ODA showed the collective average spend was unchanged at just 0.37%, only half-way to the (very) longstanding internationally agreed target of 0.7%.

In a sign of the times, another (very) longstanding target – that all NATO members should be allocating 2 % of their national budgets to defence expenditures – is also receiving unprecedented attention. The upshot may be that cuts in ODA could be even greater, as Germany, like many other European countries, is concerned not only with Ukraine but their broader security vulnerability, especially with a possible future Trump administration in the US. According to research by Germany’s Ifo Institute for Economic Research, NATO’s European members need to reallocate an extra € 56 billion a year to meet the alliance’s defence spending target. The research also showed that many of the European countries with the biggest shortfalls in being able to hit the 2% of GDP target – Italy, Spain and Belgium

– also have among the highest debt and budget deficits in Europe.26 There is also a possibility of Germany going to as high as 3.5%; such a significant amount of budget increase will need to come from somewhere – and, in some cases, from already cannibalised aid budgets.27

Third, replenishments: Pileup on the runway?

As highlighted by the Centre for Global Development, with replenishment campaigns for close to a dozen major development funds including the World Bank’s International Development Association (IDA), thematic funds like Gavi and new multilateral funds like the Loss and Damage Fund all set for 2024-2025 to the tune of over US$ 100 billion from donors over the next two years, a fundraising pile-up looms large on the horizon.28 As most funds are on three- or five-year fundraising cycles this has happened before; the last time was in 2019-2020 when 6 funds raised close to US$ 60 billion. However, the climate is much different today and there are at least twice as many funds vying for what is still a limited share of the pie. This is particularly so for a couple of reasons.

First, as noted earlier, development assistance budgets of many major donors are under great pressure this year. What’s more, many of them are heading into major elections this year, many of which are uncertain. Second, a number of new funds have been established including the Loss and Damage Fund (with approximately US$ 700 million in contributions) and the Pandemic fund (approximately US$ 2 billion raised) while the World Health Organization is hosting an ‘investment round’ in late 2024 to raise US$ 7.1 billion for its core budget for 2025-2028.29 While there are some new contributors such as the United Arab Emirates (UAE) to the Loss and Damage Fund, and China has now risen to be the sixth largest donor to IDA, all these funds will largely depend on the same donors to deliver.

What should be done?

Going forward, a number of reinforcing political and policy actions can help to start rebuild more quality funding for the UNDS, help mitigate the risk of a ‘force majeure’ funding crisis in some key parts of the UN (eg unique normative functions) and also strengthen coordination, complementarity and collaboration across the multilateral system at a time when it has rarely been so sorely needed.

Ensure greater levels of quality UNDS Funding through the new Funding Compact, the next QCPR and the upcoming UN Financing for Development (FfD) Conference

First, for the UNDS itself, the new Funding Compact for the United Nations’ Support for the Sustainable Development Goals, released with the Secretary-General’s 2024 Report on the QCPR for the Operational Activities Session of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), becomes critical as the current funding architecture of the UNDS is not fit for purpose. As noted in previous articles in this publication, five years after the adoption of the current Funding Compact, advances towards its commitments and targets have been very uneven.30

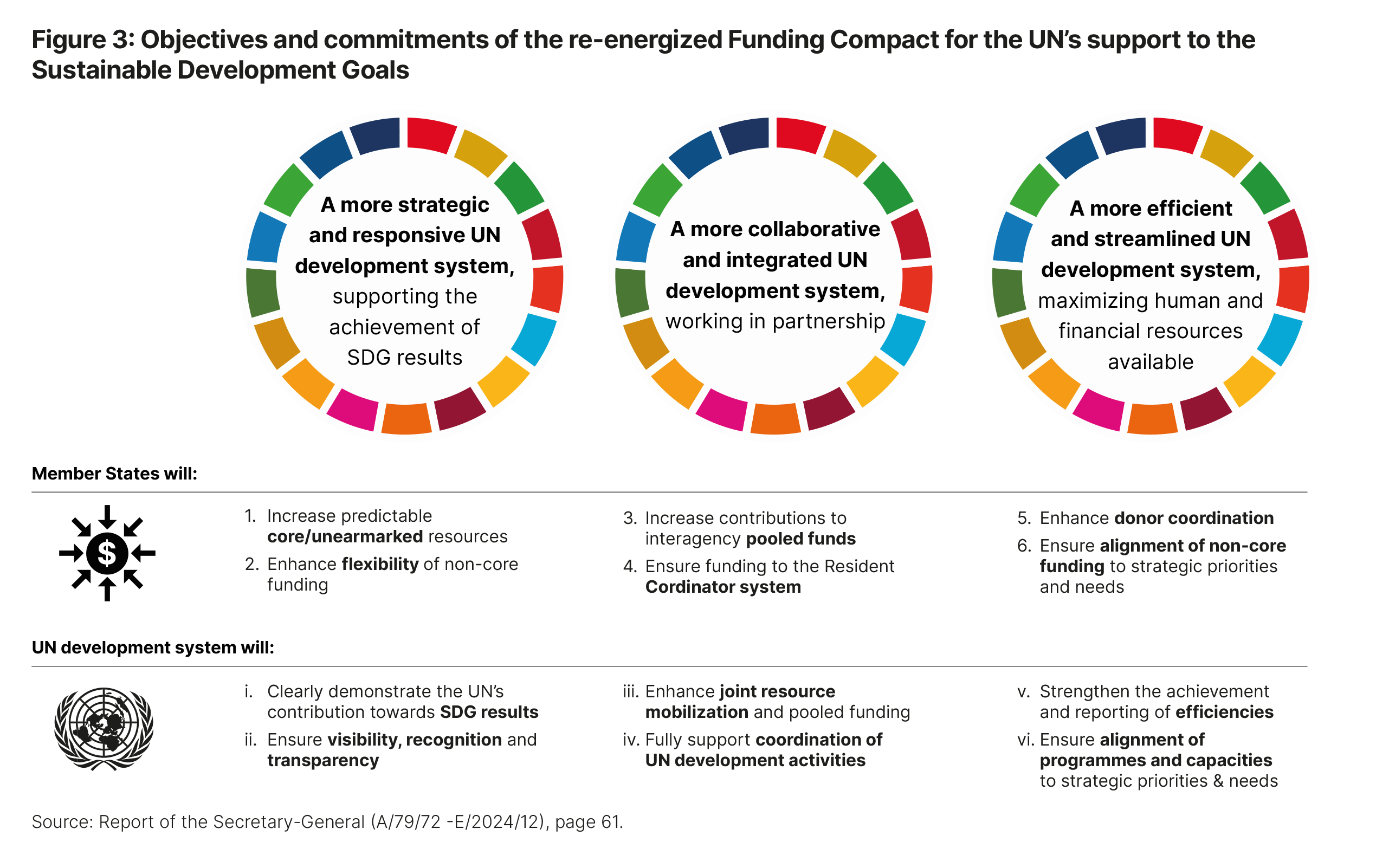

A shift towards more flexible, predictable funding requires real political will, as well as much greater awareness at senior levels in capitals where funding decisions are made, and among funding partners on the ground. A new round of dialogues with Member States and United Nations Sustainable Development Group (UNSDG) entities was held over five months with a focus on identifying commitments that are most critical to fortifying the business case for effective funding in delivering greater results. This has resulted in a new and ambitious Funding Compact – importantly shorter, simpler and more strategic – with the expectation that it will better resonate with senior decisionmakers and encourage greater buy-in at the country level.

As set out below in Figure 3, the new Funding Compact consists of 12 mutually reinforcing commitments – six by Member States and six by United Nations Sustainable Development Group entities – and a balanced number of ambitious, measurable indicators to transparently track implementation; if fully implemented, the renewed Funding Compact can be a game changer.31 Addressing continuing declines in core funding, reducing such high dependence on a limited number of contributing governments, ensuring adequate and predictable funding for the UN Resident Coordinator system, and increased resources for pooled funds will make or break the UNDS’ ability to deliver more transformative impact at a time when this is more critical than ever.

What’s more, the fact that every new multilateral fund established is a replenishment model has surely not been lost on the UN Funds and Programmes (UNDP; UNICEF; United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA); UN Women; Word Food Programme (WFP) who have depended on voluntary core (and non-core) contributions since their inception decades ago when they were primarily viewed as mechanisms for redistributing funds between North and South (and for this reason never had access to assessed contributions, with the exception of UN Women).32 While donor governments continue to indicate that a key reason they are reluctant to increase the degree of flexibility of their funding is a lack of visibility on the use of core resources despite the many efforts being made, if the Funds and Programmes don’t soon see visibility of a turnaround in core funding they may determine that securing core funding on a multi-annual basis may be better served by exploring the possibility of a ‘replenishment-like’ model synchronising policy-setting and programming over a multi-annual cycle.33

While this may be what must happen, the unintended consequences in the very near-term would make the ‘pileup’ of replenishment mechanisms that much deeper and much more complicated to prioritise and finance. Hence, it is critical that contributing countries find the political will to make the new Funding Compact a success.

The forthcoming QCPR negotiations (2025-2028), along with the Fourth Financing for Development Conference (FfD) in 2025, both present an opportunity not only to evaluate progress in accelerating SDG financing, and implementation of the Addis Ababa Action Agenda in the case of FfD, but also to address the deleterious state of UN financing today. While the upcoming Summit of the Future did not initially take up funding of the UNDS despite the dire financial situation facing it, action 42 c of revision one of the ‘Pact for the Future’ calls for sustainably funding the UNDS, including the RC system, in order to better support countries to meet their sustainable development ambitions.34

First among replenishments – The World Bank’s IDA

While there was some emphasis during the 2024 Spring meetings of how the World Bank is trying to get ‘better’ through a new scorecard, shorter project approval times and an expanded Crisis Preparedness and Response Toolkit, most of the focus was on its efforts to get ‘bigger’ by leveraging its balance sheet, through new funding mechanisms and via the upcoming IDA replenishment. Although the question of capital increase still remains, donors did pledge US$ 11 billion to some of the Bank’s innovative funding instruments including its portfolio guarantee platform, its hybrid capital mechanism and the new Livable Planet Fund which would then be leveraged to some US$ 70 billion over ten years.35

Ambitious plans were announced to provide affordable electricity to 360 million people across Africa by 2030 and 1.5 billion people with health care by 2030, although with little detail except that significantly more resources would be required. This was countered by the lack of any progress on the extraordinary debt distress in many developing countries with the ONE Campaign announcing on the eve of the meetings the sobering news that countries in the Global South are likely to pay out US$ 50 billion more in 2024 than they receive in grants and loans.36

Second, and in line with this, the World Bank’s fund for the poorest countries, the International Development Association (IDA), is in need of the ‘largest replenishment ever’ of financial resources to provide cheap loans and grants to 75 developing countries.37 Unquestionably, IDA is a very important and much needed poverty reduction vehicle – many governments see it as one of the most effective financing mechanisms as it can leverage capital markets to triple its annual windfall and provide those funds to poor countries at concessional or marginal rates.38 World Bank president Ajay Banga has indicated he is targeting US$ 30 billion in donor contributions this round which the Bank could leverage to lend or grant about US$ 100 million to borrower countries.

This would seem to take priority as IDA is an important and unique vehicle. Three prior assessments of the quality of official development assistance (QuODA), a tool developed by the Centre for Global Development for comparing performance across dimensions of aid quality across 49 of the largest bilateral and multilateral agencies, consistently found IDA to be among the best-rated organizations at delivering official development assistance (ODA).39 Using a revised methodology, QuODA 2021, ranks IDA as the third-best organisation.40 To the extent possible it will be important that China, India and South Korea, former IDA recipients who have recently become key donors, and Gulf States such as Saudi Arabia substantially increase their contributions this year if at all possible or, again, it will be ‘the usual (DAC donor) suspects’ who also overwhelmingly foot the bill for the UNDS.41

Towards a more systemic approach to funding across the multilateral system

Third, starting with the Summit of the Future through to the Fourth Financing for Development Conference in June 2025 and beyond, it is critical that government leaders start to take a more systemic look across the entire multilateral system. In doing so, it will be important that they determine what critical multilateral functions need to be sustainably financially supported – eg key normative functions like public health, human rights, gender equality and new ones including artificial intelligence; scaled up development and climate finance; humanitarian response (etc) – and where there might be opportunities for some kind of consolidation or rationalisation.

Just as the G-20 has served as an important place to discuss Multilateral Development Bank (MDB) reform with key proposals for change emanating from it, it would be important that the G-20 also does something similar on enhancing complementarity and impact across the broader multilateral system. While World Bank/MDB reform is squarely on the table now, it would be important if a couple of think tanks and/or foundations could incubate a group of very diverse and experienced thinkers and practitioners in multilateral effectiveness and reform to start to develop possible scenarios and options for greater effectiveness more systemically encompassing MDBs, the UNDS and major multilateral funds that could then be taken up in the G-20 and other key forums.

Addressing multilateral ‘Funditis’

Fourth, as outlined, a series of multilateral funds have proliferated in recent years, especially those with single-issue focus such as health or agriculture. As also noted, replenishments for such funds can generate competition for limited donor resources between organisations with replenishment models and with more normatively focused UN entities as replenishments are considered independent exercises where allocations are often made without looking across the multilateral system and without systematic information about what other donors are planning.42 This has rightfully led to calls for greater coordination of replenishments, for example by strengthening donor dialogue on resource needs and better understanding of the performance of multilateral organisations through such mechanisms as Multilateral Organization Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN) assessments as well as perhaps QuODA 2021 as outlined above. Better coordination and clearer communication among donors on how they intend to distribute multilateral funding across the system is much needed today.43

Coordination is important but so too is consolidation. As Bright Simons, Vice President of research at Ghanaian think tank Imani puts it ‘there is an issue of duplication, where too many funds seem to be chasing similar prospects – without coordinating their investments’. This results in an ‘overheads overhang’ where multiple bureaucracies are ‘all marketing a bewildered array of poorly differentiated financing solutions to overwhelmed developing countries’.44 While some of these funds can take in alternative private sources of investment such as philanthropic contributions which is key, many legally cannot.

One clear candidate for massive consolidation is multilateral climate funds. As outlined in the UN’s Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 6, there are currently 62 multilateral funds on climate disbursing only US$3 billion to US$4 billion in total in 2020.45 While the UN policy brief suggests consolidating the disperse climate mitigation funds and replenishing the Green Climate Fund (GCF) as the primary climate finance vehicle, the total portfolio of the GCF is only US$ 10.6 billion. Consequently, a recent policy review questioned both whether it is reasonable to expect the GCF to manage the trillions needed for climate mitigation or if an intergovernmental body – whether GCF or the World Bank – was the best suited for mobilising private capital for the energy transition and natural capital?46

Instead, the Brookings policy paper highlights an approach proposed by Hafez Ghanem to replace the 62 multilateral climate mitigation funds by a Green Bank which would be different from existing MDBs in five ways: (1) it would be a public-private partnership with private and government shareholders; (2) countries of the Global South and the Global North and private actors would have equal voice in its governance; (3) it would only finance mitigation projects; (4) it would only provide financing (equity, loans, and guarantees) to private projects without adding to governments’ debts or asking for government guarantees; and (5) it would specialise in mobilising innovative forms of financing such as the sale of carbon credits and green bonds.47 Simply put, it is proposed that a Green Bank that has private shareholders and uses innovative financing instruments to leverage public money would be more effective than 62 multilateral climate mitigation funds.

In moving to greater complementarity, if not some kind of rationalisation, it will be important to build on other experiences such as global health where there is a plethora of big multilateral funds. Here the Future of Global Health Initiatives (FGHI), a time-bound, multistakeholder process involving representatives from across funders, governments, global health organisations, civil society and the research and learning community, came together to identify and support opportunities for various global health initiatives (GHI) to maximise health impacts as part of country-led trajectories toward Universal Health Coverage.48

The Lusaka Agenda, the conclusions of the FGHI, was agreed in December 2023, and highlighted the importance of partners developing a common vision where the future role of development assistance for health is coherent, catalytic, country-driven and complementary to domestic investments. Discussions are to be linked with broader processes on development assistance, financial architecture and debt relief as well as responding to critical challenges posed by climate change and other global challenges affecting health. The creation of new GHIs is to be avoided, with an emphasis instead on strengthening and enabling flexibilities within existing structures and systems to address priority needs.49

How to best move towards greater coordination, consoli-dation and rationalisation of the plethora of multilateral funds should be high on the list of priorities for the aforementioned analytical work on a more systemic approach across the multilateral system.

Towards greater complementarity and collaboration amongst the World Bank and MDBs as well as the World Bank/MDBs and the United Nations

Fifth, with the entire multilateral system under great strain, enhanced complementarity and collaboration not only between the World Bank and the UN but also starting with MDBs themselves becomes imperative. On the margins of the Spring Meetings the heads of nine MDBs and the World Bank announced joint steps to enhance their work as a system in five areas: (1) scaling-up MDB financing capacity; (2) boosting joint action on climate; (3) strengthening country-level collaboration and co-financing; (4) catalysing private sector mobilisation; and (5) enhancing development effectiveness and impact.50

For many observers, though, there is much more that can be done. As Rachel Kyte, Professor of Practice in climate policy at the University of Oxford, said in a Devex podcast post-Spring Meetings in response to a question whether development finance institutions, including MDBs, can work together on a given country’s priorities: ‘sounds obvious; doesn’t exist at the moment’ Kyte said. ‘We’ve seen extraordinary fragmentation in development aid over the last 20 years. Private sector finance gets leveraged deal by deal, rather than being pooled. And so, it is a good idea. But where is the radical collaboration?’51

Closer collaboration, and greater complementarity, between the UNDS and the International Financial Institutions (IFIs) is also essential to see greater progress against the SDGs. The UN and the World Bank are now collaborating in over 50 countries, including on prevention, food security and forced displacement, among other areas. Contributions from IFIs for UN development activities doubled between 2021 and 2022 and now account for 5 per cent of total funding.52 In 2023, the United Nations Peacebuilding Support Office’s Partnership Facility supported collaboration between the UN and IFIs in more than a dozen country and regional settings, to enable joint data and analysis and facilitate advisory support to Resident Coordinators/Humanitarian Coordinators and UN Country Teams.53

That said, when asked via recent DESA surveys about collaboration between IFIs and UN Country Teams since the repositioning of the UNDS in 2019, 62% of programme country governments responded that collaboration has improved to a medium to large extent.54 While it is an improvement on 2022, there is much more to be done. According to a recent report by MOPAN on MDBs and Climate Change, joint monitoring and joint analytics by MDBs should be prioritised and means of providing concessional finance should be harmonised among partners at country-level to ensure that critical upstream support is consistently given priority. Beyond facilitating deeper MDB co-ordination, these approaches should consider how to harmonise processes to strengthen partnerships with other development actors, including the United Nations, to promote a more coherent ‘whole-of-society’ approach and reduce fragmentation.55

On the UN side, findings from external evaluations confirm that the UNDS needs to reorient some of its capacity to enhance its offer around Integrated National Financing Frameworks (INFFs) so as to better meet increasing and more complex demands and enhance collaboration with MDBs, IFIs and other public and private financing partners.56 And there is also untapped potential for the UN to act as a technical partner to MDB financing such as loans, grants, and policy-based lending rather than outsourcing technical assistance work to largely private firms/consultancies or in some cases non-governmental organisations.

Conclusion

While preliminary ODA figures for 2023 are again higher than the previous year, when you look beyond the aggregate there are a number of concerns – none more serious than that four of the top five ODA providers, who also fund almost half of the UNDS, will be reducing significantly in 2024. For the UNDS, this portends to an even further deterioration in the quality of the funding it receives thereby undermining its core mission and compromising the multilateral nature of UN support. The new Funding Compact, and its ability to engage senior decision-makers, will be critical.

Going forward, with the multilateral system under great strain – and with so many institutions and funds competing for grants and/or replenishments – there is a pressing need for leaders to look across the whole system in terms of relative comparative advantage, how to incentivise greater complementarity and, importantly, how to ensure that the unique assets of the multilateral system, such as the normative role, are adequately funded. As this new era of polycrisis has tragically shown, less money for sustainable development today often translates into greater spending on humanitarian crises tomorrow.

The author would like to gratefully acknowledge the very helpful comments by Ingrid FitzGerald, Nilima Gulrajani and Silke Weinlich on an earlier draft.

Endnotes

There are many studies outlining the negative impact of tightly earmarked donor financing of UN development work including a recent piece by Max-Otto Baumann and Sebastian Haug, ‘Financing the United Nations: Status quo, challenges and reform options’, (Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung: Bonn, April 2024), https://ny.fes.de/article/financing-the-united-nations-status-quo-chall….

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, ‘International aid rises in 2023 with increased support to Ukraine and humani- tarian needs’, online. https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/international-aid-rises-in-2023- with-increased-support-to-ukraine-and-hum- anitarian-needs.htm#:~:text=On%20a%20global %20level%2C%20humanitarian,compared%20 with%2014.7%25%20in%202022.

The Editorial Board of the Financial Times, ‘Crises are eating into development funding’, (London: Financial Times, April 16, 2024), https://www.ft.com/content/3bb91a00-9a92- 4f71-9719-c98e092e89fc.

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, ‘Global Humanitarian Overview 2024’, (New York, OCHA, December 2023), https://humanitarianaction.info/.

United Nations Secretary-General, ‘Implementation of General Assembly Resolution 75/233 on the quadrennial comp- rehensive policy review of operational activities for development of the United Nations System: Funding of the United Nations Development System’ (A/79/72/Add.1-E/2024/12/Add.1),

(New York: United Nations, 2024), p. 8.

Alecsondra Kieren Si, ‘6 things we learned from the 2023 ODA figures’, Devex Pro,

22 March, 2024, https://www.devex.com/news/6-things-we-learned-from-the-2023-oda-figure… majority%20of%20donors%20gave,gene rous%20compared%20to%20other%20donors.

Adva Saldinger, ‘2024 US foreign affairs funding bill a ‘slow-motion gut punch’, Devex, 22 March, 2024, https://www.devex.com/news/2024-us-foreign-affairs-funding-bill-a-slow-….

Burton Bollag, ‘How Germany is cutting billions from foreign aid’, Devex, February 19, 2024, https://www.devex.com/news/how-germany-is-cutting-billions-from-foreign… Parliament%20in%20January,from%20the%20 humanitarian%20aid%20budget.

SEEK Development, Donor Tracker, German Finance Ministry plans signal further reductions to BMZ April 2, 2024 | Germany, See https://donortracker.org/policy_updates?policy =german-finance-ministry-plans-signal-further-reductions-to-bmz-2024.

Rob Merrick, ‘UK aid spending on refugee hotel bills soars to 3.2 billion GBP’, Devex, March 14, 2024, https://www.devex.com/news/uk-aid-spending-on-refugee-hotel-bills-soars….

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development – Development Assistance Committee Peer Review – Mid-term Review of the United Kingdom, (Paris: OECD, March 4, 2024), https://one.oecd.org/document/DCD/DAC/AR(2024)3/17/en/pdf.

Burton Bollag, ‘French Government criticized over $806M cut to aid’, Devex Pro, March 6, 2024, https://www.devex.com/news/french-government-criticized-over-806m-cut-t….

Dylan Robertson, ‘Liberals buck global trend by ‘doubling down’ on foreign aid, as sector urges G7 push’, The Canadian Press, April 18, 2024, https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/liberals-buck-global-trend-in-doubling-…- push-1.6852097.

See SEEK Development, Donor Tracker, https://donortracker.org.

Devex estimates that if inflation and economic growth remain at 2023 levels for the next two years Swedish aid spending will be 11% lower in 2025 than it would have been if still directly linked to GNI. Burton Bollag, ‘Why Sweden tore up its funding agreements with its NGO partners’, Devex, April 5, 2024, https://www.devex.com/news/why-sweden-tore-up-its-funding-agreements-wi….

Martin Arnold, Paola Tamma and Henry Foy, ‘Europe faces EUR 56 billion NATO defence spending hole’, (London: Financial Times, March 16, 2024), https://www.ft.com/content/ 99facdd9-bb1d-4ed3-93ef-d059acf4b0ce.

Janeen Madan Keller, Clemence Landers and Nico Martinez, ‘The 2024-2025 Replenishment Traffic Jam: Are We Headed for a Pileup?’ Blog Post, Center for Global Development, February 8, 2024, https://www. cgdev.org/blog/2024-2025-replenishment-traffic-jam-are-we-headed-pileup.

See John Hendra, ‘The Funding Compact going forward: More quality financing for critical outcomes’ in Financing the UN Development System – Choices in Uncertain Times (Uppsala: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, 2023), pp. 172-177; and John Hendra,

‘Two steps forward, one step back? The UN Funding Compact at three years old’ in Financing the UN Development System – Joint Responsibilities in a World of Disarray’, (Uppsala: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, 2022), pp. 119-122.

UN Secretary-General, ‘Implementation of General Assembly Resolution 75/233 on the quadrennial comprehensive policy review of operational activities for development of the United Nations System: Funding Compact for the United Nations’ Support to the Sustainable Development Goals (A/79/72/Add.2-E/2024/ 12 /Add.2), (New York: United Nations, 2024).

Note: ‘Pact for the Future’ (14 May, 2024) was prepared by the Permanent Representatives of Germany and Namibia to the United Nations in their role as Co-facilitators of the intergovernmental preparatory process of the Summit of the Future (SoF). The SoF will be held at UN Headquarters in New York 22-23 September, 2024. See https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/sotf-pact-for-the-future-rev….

Adva Saldinger, ‘Highlights and lowlights from the World Bank/IMF Spring Meeting’, Devex Invested, April 23, 2024, https://www. devex.com/news/devex-invested-highlights-and-lowlights-from-the-world-bank-spring-meetings-107507.

David Ainsworth, ‘Global South now repays more in debt than it gets in grants and loans’, Devex, April 18, 2024, https://www.devex.com/ news/global-south-now-repays-more-in-debt- than-it-gets-in-grants-and-loans-107490.

Joseph Cotterill and Aiden Reiter, ‘World Bank lender to poorest nations seeks record funding haul’, Financial Times, March 17,2024, https://www.ft.com/content/e4cb61c5-14b9- 4e14-8e31-7670039c6865.

Homi Kharas and Charlotte Rivard, ‘Investing in Development Works’, Commentary, Brookings Institution, April 2, 2024, https://www.brookings. edu/articles/investing-in-development-works/.

Centre for Global Development, https://www. cgdev.org/quoda-2021.

Aiden Reiter and Joesph Cotterill, ‘Development funds dash for donor cash at World Bank and IMF meetings’ Financial Times, April 15, 2024, https://www.ft.com/content/385645bd-8a9c-4bbc-8274-2eaecf2cc847.

United Nations, ‘Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 6 – Reforms to the International Financial Architecture’, May, 2023. https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/our-common-agenda-policy-brie….

See Hafez Ghanem, “The World Needs a Green Bank”. Policy brief 06/23, Policy Center for the New South https://www.policycenter. ma/sites/default/files/2023-02/PB_06-23_ Ghanem.pdf and Hafez Ghanem, “8 reasons to Support a New International Green Bank.” Policy note 8, Finance for Development Lab. https://findevlab.org/a-new-international-green-bank-8-reasons-to-suppo…

See ‘The Lusaka Agenda: Conclusions of the Future of Global Health Initiatives process’, https://d2nhv1us8wflpq.cloudfront.net/prod/

Asian Development Bank, ‘Heads of MDBs Viewpoint Note: MDBs Working as a System for Impact and Scale’. Washington, D.C. April 20, 2024, . https://www.adb.org/news/viewpoint-note-mdbs-working-system-impact-and-…, file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/Heads%20of%20MDBs%20 Viewpoint%20Note%20-%2020%20April%20 2024%20(1).pdf

Multilateral Organization Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN), ‘Brief on Lessons in Multilateral Effectiveness: MDBs and Climate Change’, 2024, p. 17, https://www.mopanonline.org/analysis/items/lessonsinmultilateraleffecti….