Silke Weinlich is a Senior Researcher at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS) where she leads a research and policy advice project on the United Nations development system and its reform needs. Over the last 15 years, she has followed UN reform processes in fields ranging from peacekeeping to sustainable development.

Nilima Gulrajani is a Senior Research Fellow at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) and Visiting Fellow at King’s College Department of International Development. She has spent 15 years of researching bilateral aid governance and reform and implications for the global development architecture.

Sebastian Haug is a Post-Doctoral Researcher at the German Institute of Development and Sustainability (IDOS) and Ernst Mach Fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences (IWM). After working for the United Nations in Beijing and Mexico City, he has spent the last seven years researching multilateral politics, South-South cooperation and global power shifts.

In May 2022, the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Member States took the historic decision to increase the share of assessed contributions in the organisation’s regular budget from 16% to 50% by 2028. While future budget negotiations will show whether Member States honour their commitments, the political signal is clear. Member States want to provide a more sustainable financial footing for WHO which is currently overly dependent

on voluntary earmarked funding, including from private actors. The pitfalls of (certain forms) of earmarked funding have been widely discussed, not least in previous editions of this report. Assessed contributions represent an important alternative route to sustainable financing for multilateralism as they cannot be arbitrarily withdrawn – they are membership fees that all states are obliged to contribute. Assessed contributions can also be re-purposed in line with an international organisation’s mandate and core organisational needs, thereby enabling the organisation to act more effectively, independently and with greater authority.1

The WHO decision, addressing a well-analysed problem and following 18 months of difficult consultations, is path-breaking for the wider United Nations system. WHO is just one organisation among many where a zero-nominal growth paradigm has been stifling core budgets (since the 1980s), while voluntary (earmarked) resources have grown drastically. Proponents of zero- nominal growth in core resources – mainly the largest contributors – have also opposed assessed contributions being used for new tasks such as securing the funding of the Resident Coordinator system.2

There are good reasons to assume the increase in the assessed contributions share at the WHO during the COVID-19 pandemic is a singular measure, unlikely

to be repeated for other UN entities in the near future. Opposition may stem from austerity considerations and/ or dissatisfaction with an organisation’s effectiveness and efficiency. Also implicitly at play, however, may be discomfort with a more autonomous international bureaucracy, leading to a desire to limit funds whose use is jointly decided by UN members (as opposed to earmarked funds which give individual providers more leeway).

On the road to the UN Summit of the Future in September 2023, however, assessed contributions – which remain an underexploited instrument for collectively funding global tasks – should not be discarded prematurely. Given current global instability and crises, expanding and reforming their usage could help make UN organisations and multilateral action more effective. Equally important in times of geopolitical upheaval, assessed contributions symbolise a commitment to collectively shared responsibility and a belief in multilateral priority setting, as cumbersome as this may be.

Assessed contributions in the UN system

Previous editions of this report have dedicated considerable attention to voluntary and innovative forms of funding, frequently from non-state actors. By contrast, assessed contributions have rarely been mentioned, perhaps due to the relatively small and stagnating share of total UN resources they constitute.

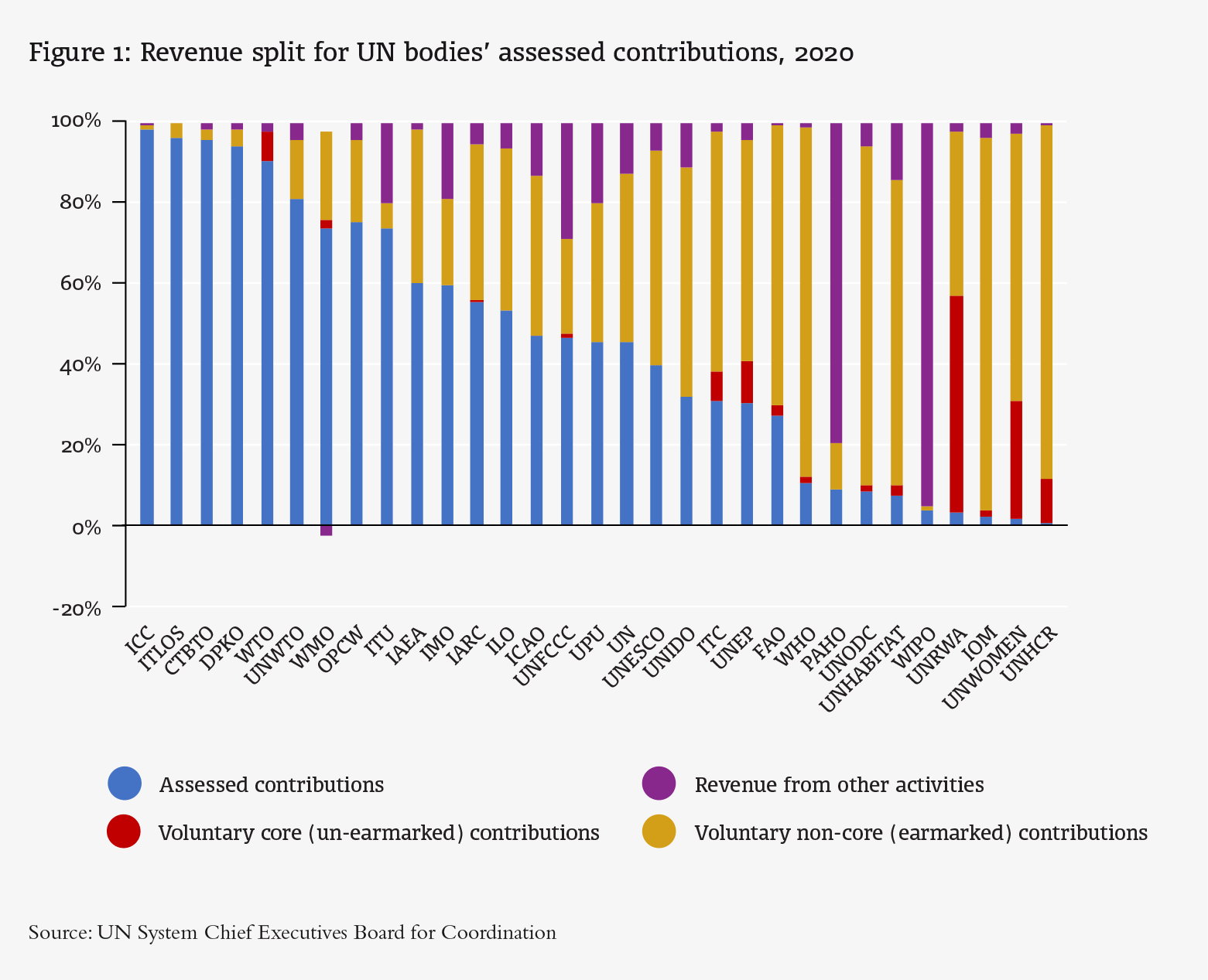

The overall share of assessed contributions in the UN’s total revenue stood at 21.9% in 2020. Of the 31 UN organisations receiving assessed contributions in 2020, 18 received more than half their total revenues from other sources (see Figure 1). As a general pattern, forum organisations that predominantly set global rules and support decision- making – such as the World Trade Organisation – are funded mainly by assessed contributions. By contrast, organisations like WHO, which also engage in operational activities on the ground, rely to a large degree on voluntary sources of funding (the one notable exception being peacekeeping).

Assessed contributions provide flexible and reliable funds, and can ensure a UN entity’s institutional independence and integrity. Even so, they by no means represent a cast- iron guarantee for a solidly financed multilateral organisation, nor are they a panacea for funding global goods.

Upsides and downsides of assessed contributions

The UN and individual UN organisations have been on the brink of insolvency several times due to Member States withholding their mandatory payments, paying late or failing to pay the full amount due. In April 2022, for example, unpaid assessments to the UN regular budget amounted to more than half the total assessment for that year.3 While non-payment may be the result of austerity or financial crises, payment morale is often linked to political considerations. The scale of assessments distributes the costs of UN membership among all Member States. Given that economic power is the most important variable in determining assessment rates, however, the brunt of the costs is borne by only a small number of countries. In the 2019-2021 assessment period, the five largest contributors alone – the United States (22%), China (12%), Japan (8.6%), Germany (6.1%), and the United Kingdom (4.6%) – contributed more than half of the regular UN budget, paying more than the other 188 Member States combined.

While imperfect, the scale arguably operationalises collective responsibility in a more nuanced way than, for example, the principle of common but differentiated responsibility in the climate regime, which is based on a binary distinction between developing and developed countries. It is noteworthy that the scale of assessments has accommodated the economic rise of large middle- income countries without major disruption, despite the – in both absolute and relative terms – substantive increases in their contributions, particularly in the case of China. Given that all Member States are required to make a contribution, however, there are also ownership advantages of financing via assessed contributions over a wholly voluntarily financed scheme.

Though assessed contributions impose more substantive limits to unilateral influence than voluntary funding, they do not prevent power politics from influencing programmatic and budgetary decision-making.4

Even if assessed contributions arguably protect global institutions from individual Member State priorities to a greater degree, political controversies – about the value of human rights or the role of civil society, for instance – are carried into budgetary decisions.

Increasing geopolitical tensions further complicate the picture. While China’s future economic growth is difficult to predict, the country could have a regular budget share at the UN matching that of the United States as soon as 2028.5 On the one hand, China’s growing share of the UN’s regular budget potentially lowers the budget burdens of others. On the other hand, China is expected to make use of its increased financial clout to advance its interests through the UN system.

The way forward

Expanding and reforming the use of assessed contributions

The inherent challenges of the scale of assessments and related budgetary and programmatic decisions notwithstanding, assessed contributions have thus far been an underexploited tool in the UN system and could be allocated a larger space in the overall funding mix. Historically, it seems Member States only agreed to an obligatory funding model because they expected costs to be modest, supporting the work of the UN as a conference organisation.6 Yet, as outlined by Secretary-General Guterres in his 2021 flagship report Our Common Agenda, the UN needs to become a more meaningful actor in the protection and provision of global commons and global public goods.7 Several of the UN entities that receive assessed contributions could play a more important role in this regard. An increase in assessed contributions would be one step towards ensuring that they are better equipped for this task.

Linking funding reform discussions and the UN’s desired global functions

While the functional expectations of multilateral organisations will always face political imperatives, the WHO example offers an opportunity to articulate the desired global governance functions of UN entities and the different forms of funding needed to implement them. There is no need to start from scratch – recent conversations around the reform of the UN development system and the funding compact (see John Hendra’s contribution in this report), as well as the process around Our Common Agenda, provide a good starting point. The discussion about UN global governance functions should have a dedicated financial dimension and include a focus on the right match between functions and funding: Do assessed contributions provide the best revenue stream in each case? Where are other forms of funding more appropriate, such as replenishments, fees, negotiated pledges, or soft and hard earmarking?8

Making the formula for assessed contributions fit for a world of transnational challenges

While various components of the UN scale of assessments have evolved since the 1940s, for the past 20 years the formula has remained remarkably stable. It weights contributions according to a country’s economic strength and population size, with adjustments made on the basis of income per capita and debt burden, the intention being to ensure fair financing obligations across countries of dissimilar means. The formula’s minimum contribution currently stands at 0.001% of the regular UN budget, while its maximum contribution is 22%.

In order to ensure this basic formula remains fit for purpose in the context of profound global power shifts and existential transnational challenges, Member States should explore the possibility of adding indicators to the scale of assessments for specific UN bodies. Here, the premium on peacekeeping costs paid by the Security Council’s five permanent members serves as a case in point. While a fine balance needs to be struck between mobilising resources and operationalising differences in capabilities and responsibilities, issue-specific dimensions could help in updating the regular budget formulas of individual entities. For example, should a Member State’s climate change vulnerability be factored in? Or its carbon footprint? Or its readiness to host large refugee populations?

Such dimensions could also add a merit-based element to the question of who absorbs the costs of global governance. Any change to the formula is likely to be controversial, as it will shift the distribution of costs among Member States at a time of extreme geopolitical sensitivity and fiscal constraint. The review of the formula would also not be complete without asking whether the cap of 22% (the ceiling currently limiting the share of assessed contributions assigned to any given Member State) should not be significantly lowered to reduce dependencies.

Strengthening mechanisms that penalise arrears

One of the main challenges of the UN’s current assessed contribution system is that a small but significant number of Member States pay late, partly, or not at all. In April 2022, by far the largest debtor to the UN's regular and peacekeeping budgets was the United States, followed by China and Brazil. To counter such ‘low payment morale’, a more comprehensive set of mechanisms should be considered to increase timely and full compliance with assessed contribution obligations. As a first step, more transparency across the system could be introduced. System-wide data on arrears – i.e. late payments – should be as easily accessible on the Chief Executives Board’s website as that on funding flows.

The assessed contribution formula itself could be adapted by using a variable that factors in past payment performance when calculating budget allocations. Tightening sanctions for non-payment by lowering the threshold beyond which Member States lose their voting rights at UN assemblies if they do not pay their dues, or do not pay on time, could also be considered. Throughout, a more explicit distinction should be made between an inability to pay – in the case of emergency situations in least developed countries, for instance – and an unwillingness to pay for geopolitical or other strategic reasons.

Conclusion

The decision to gradually increase the share of assessed contributions at WHO is good news for multilateralism, which has otherwise suffered many setbacks this year. Despite various controversies, there is agreement that UN organisations provide unique global governance functions, and that all Member States are willing to invest in and strengthen them. The Summit of the Future will provide an opportunity to apply this insight more universally across all UN bodies in receipt of assessed contributions. An honest reflection will require a reassessment of the essential global functions the UN system can play in an increasingly polarised and unstable world.

Footnotes

For a more comprehensive explanation of why assessed contributions need to be increased and how the new measures will work, see World Health Organization, ‘Rationale for an Increase in Assessed Contributions’, 21 April 2021, https://apps.who.int/gb/ wgsf/pdf_files/wgsf7/WGSF_7_INF1-en.pdf.

SilkeWeinlich,‘The Review of the Resident Coordinator System: Give UNDS reform a chance!’, German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) blog, 21 July 2021, https:// blogs.die-gdi.de/2021/07/21/the-review-of-the-resident- coordinator-system-give-unds-reform-a-chance/.

See Catherine Pollard,‘The United Nations Financial Situation’, 5 May 2022, www.un.org/en/ga/contributions/ Presentation%20May%202022.pdf.

Wasim Mir,‘Financing UN Peacekeeping:Avoiding Another Crisis’, International Peace Institute (IPI), 2019, p. 10, www.ipinst.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/1904_ Financing-UN-Peacekeeping.pdf.

Erin R. Graham,‘The institutional design of funding rules at international organizations: Explaining the transformation in financing the United Nations’, European Journal of International Relations, 23/2 (2017), pp. 365–90, https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066116648755.

United Nations, Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary- General (New York: UN Publications, 2021), www.un.org/ en/content/common-agenda-report/.