Bernhard Reinsberg is Professor of International Political Economy and Development at the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. His research is on the policies and politics of international development organisations and development cooperation more generally.1

Cecilia Corsini is a postdoctoral research associate in the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow. Her rese-arch interest is in international organisations, specifically on competition between United Nations agencies in humanitarian assistance.

Giuseppe Zaccaria is a postdoctoral research associate at the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Glasgow. His research interest is on the challenges to international organisations, particularly in development, finance, and trade.

Introduction

The principle of ‘ownership’ in development assistance seeks to empower recipient countries by allowing them to set their own development priorities.2 Ownership is therefore seen as critical for achieving sustainable outcomes.3 However, how donors engage can affect their ability to promote recipient-country ownership. As part of a larger inquiry on multilateral aid effectiveness,4 we examined whether and how earmarked assistance affects recipient-country ownership.5 Our findings reveal that earmarked assistance — especially if strictly earmarked — undermines recipient-country ownership.

Earmarked development assistance matters

How countries provide development assistance has changed a lot. They used to mainly choose between giving money directly to another country, more commonly known as bilateral assistance, or to international organisations like the United Nations, that is seen as multilateral assistance.6 Nowadays, donors often opt for the latter modality, but with strict rules on how their money must be spent identified as earmarked assistance. This means donors choose exactly which countries, issues, or projects to support.

Although the increase in earmarked funding is well-studied from the perspective of development organisations, the impact on recipient countries is often overlooked.7 To address this, we analysed historical data on the three main channels of development assistance – bilateral, multilateral, and earmarked – for individual countries.8

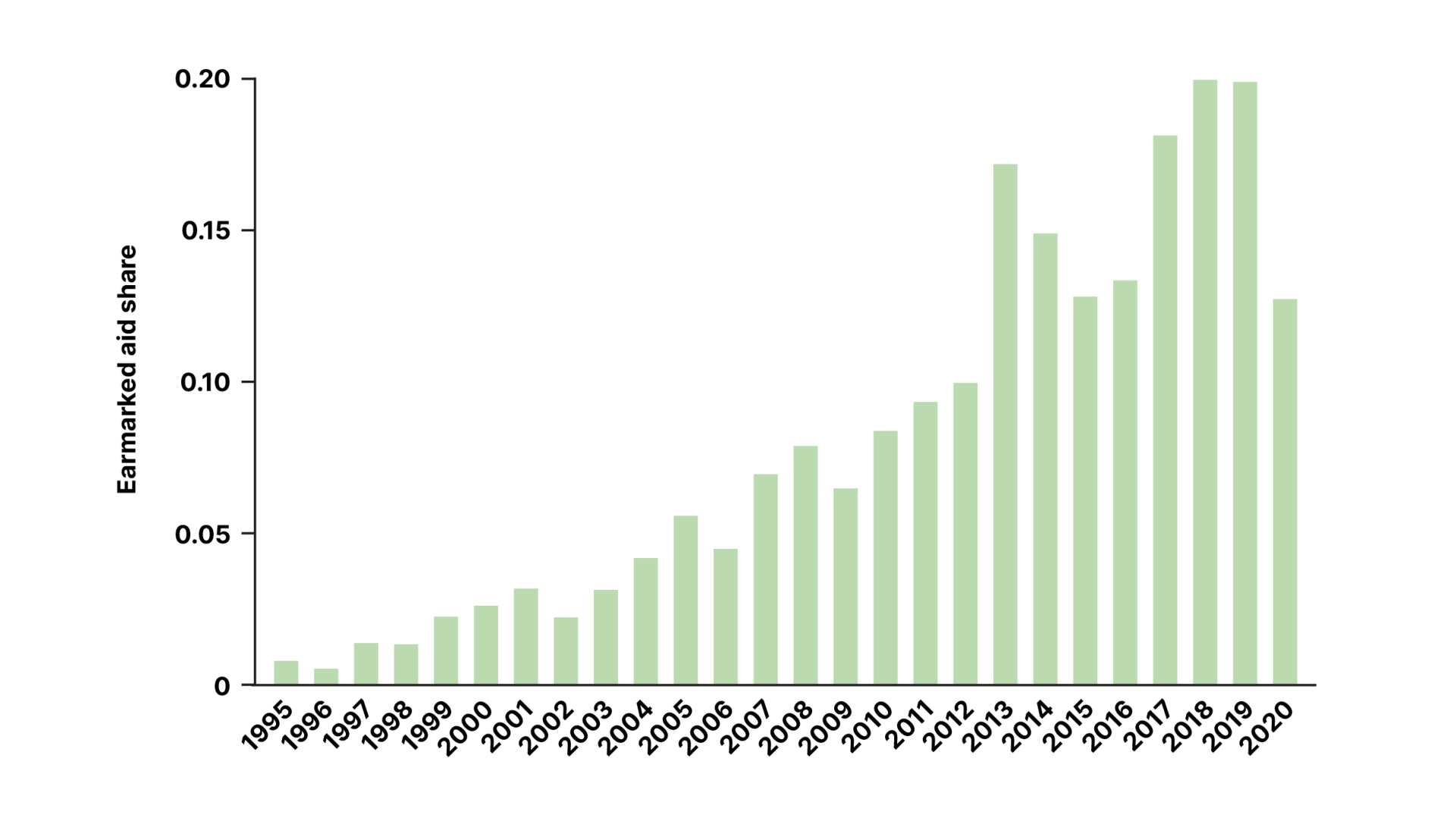

We calculated the proportion of development assistance that a country gets that was earmarked and then determined the average earmarked development assistance share across all countries.

Our analysis, depicted in Figure 1, reveals a significant rise in the share of earmarked development assistance. Before the year 2000, earmarked development assistance represented less than 5% of the total development assistance portfolio. However, in the period immediately preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, this figure had increased to approximately 20%.

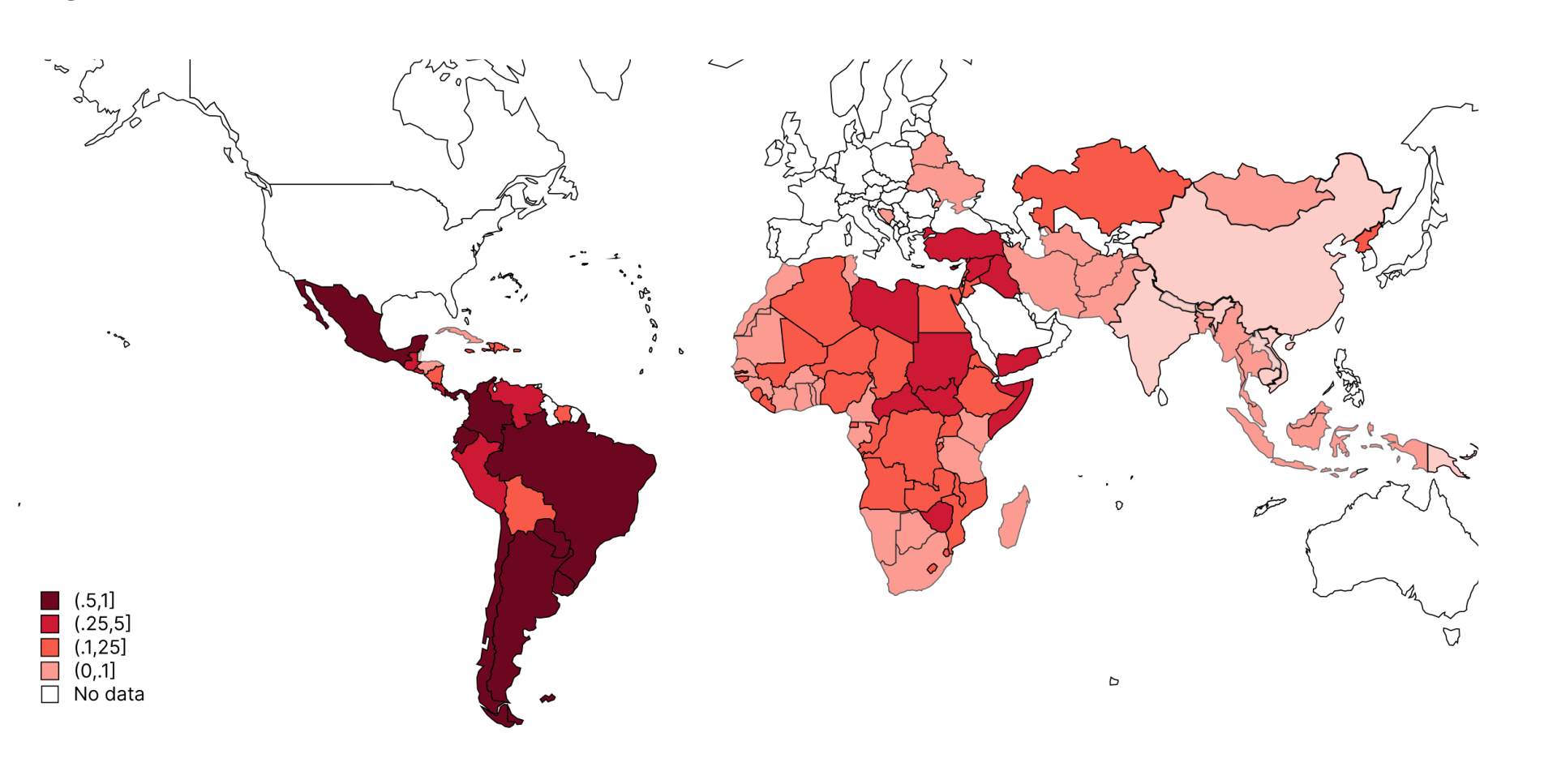

While the average earmarked development assistance share has grown, this support reliance varies by country (see figure 2). From 2016 to 2020, upper-middle-income nations, especially in Latin America, received over half of their development assistance as earmarked funds. Earmarked development assistance shares ranged from 25% to 50% in North African and Central Asian countries, and from 10% to 25% in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Earmarked funding makes up for a growing share of country-level assistance

Source: Earmarked Funding Dataset (Reinsberg, Heinzel and Siauwijaya 2024).

Earmarked aid shares across countries

Source: Own compilation based on Stata package ‘spmap’ (Pisati 2007) and data from Earmarked Funding Dataset (Reinsberg, Heinzel, and Siauwijaya, 2024).9

An unresolved theoretical debate

The impact of earmarked assistance on recipient countries’ degree of control over their development is a much-debated topic. There are two main viewpoints: The first, aligned with official donor statements, suggests it can improve coordination. The other, offering a more critical view, argues it undermines recipient control.

Many donors claim that earmarked funding, particularly through multi-donor trust funds (MDTFs), can improve donor coordination.10 These funds can attract more donor support and, by bringing donors together, facilitate political dialogue and reduce the burden on recipient countries’ development assistance management. However, for these benefits to materialise, donors must genuinely commit to MDTFs and reduce their individual, separate development assistance projects, which is often challenging.11

A critical perspective emphasises the downsides of ear-marked funding for recipient-country ownership. Although recipient governments may, in certain instances, welcome earmarked funding when it is specifically allocated to their nation, it more commonly imposes constraints on the utili-sation of funds.12

These constraints may limit expenditures to specific thematic areas or mandate support for narrowly defined interventions at the national level, which may not align with national development plans or address the most pressing development needs.13

Hence, as recipient countries finance their development programs with a progressively larger proportion of donor-restricted resources, their ownership will suffer.

Monitoring and measuring alignment

To adjudicate between these competing views, we collected data from two monitoring rounds of the Global Partnership on Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC).14 The moni-toring framework uses stakeholder surveys and other data sources to assess how well development partners perform against their commitments under the aid effectiveness agenda.15

We focused particularly on the four indicators measuring alignment. In our view, these indicators capture the extent to which donors promote country ownership well. They measure alignment at objectives level, results level, monitoring and statistics level, and joint evaluations.

Using the full dyadic GPEDC monitoring dataset,16 covering over 80 donors and 92 recipient countries, we employed factor analysis to confirm that the four indicators are positively correlated with each other and load onto a single latent ‘alignment score’.17

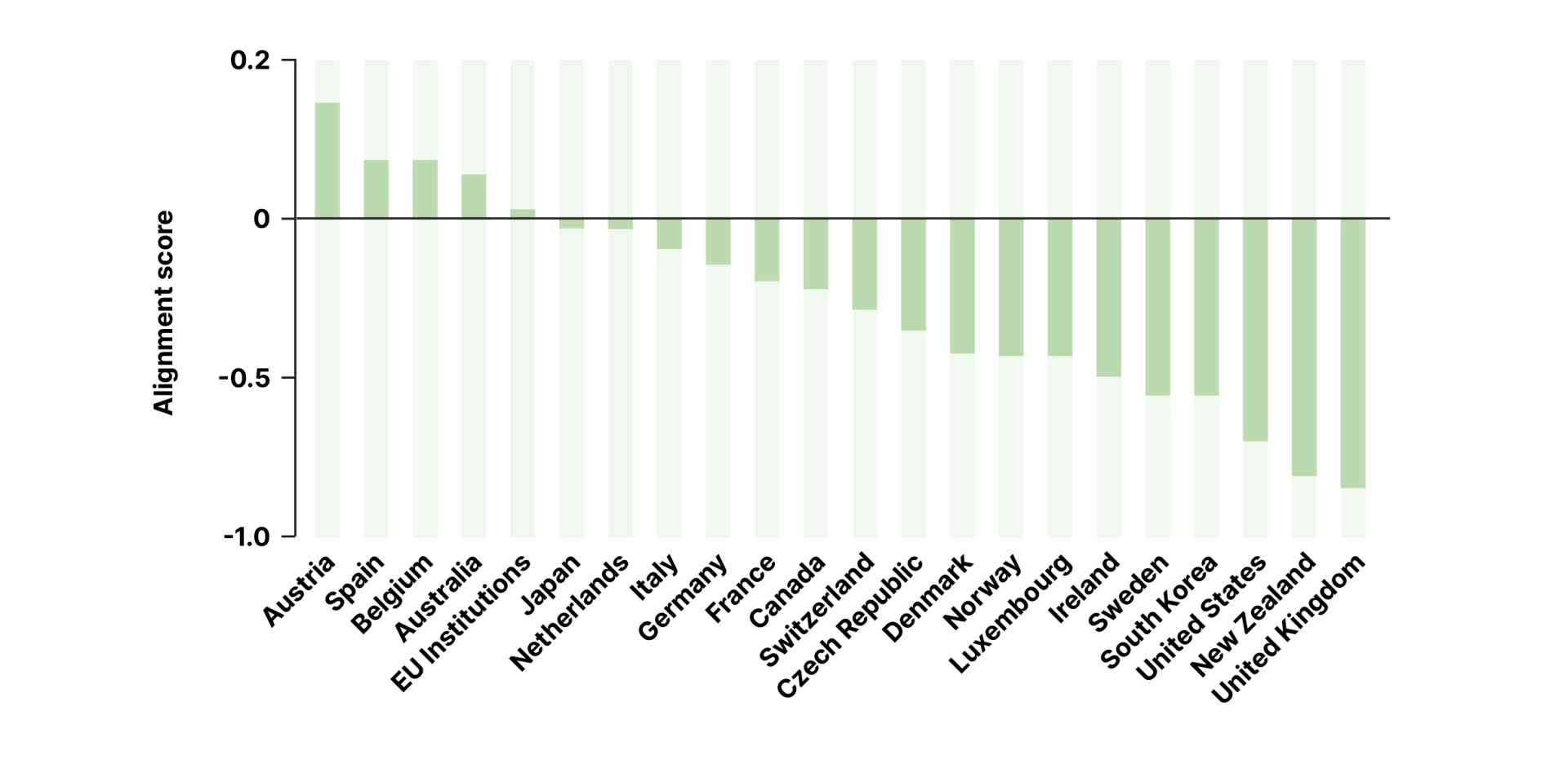

The alignment score has an average of zero and a standard deviation of one which means that the bulk of the observations falls within a band around the mean. Positive scores indicate better performance and negative scores weaker performance toward promoting ownership.

Exploring our novel alignment score descriptively, we first ranked all bilateral Development Assistance Committee (DAC) donors. Figure 3 shows that some of the smaller donors such as Austria, Spain, Belgium, and Australia appear to perform best, while some large donors like the United Kingdom and the United States appear to score worst.18

Alignment scores across DAC donors

Notes: Author calculations based on source data from GPEDC (2022).

Earmarked development assistance and ownership

We use our ‘alignment score’ to examine whether different levels of donor engagement with earmarked assistance affect donors’ ownership performance. To measure ear-marked assistance, we rely on the Earmarked Funding Dataset — the largest available dataset on the earmarked aid activities of 50 donors with 340 international organi-sations from 1990 to 2020.19

Besides its broad coverage, a key advantage of the data-set is to provide measures of earmarking stringency that are comparable across a wide range of international organisations.20 This allows us to distinguish between ‘softly’ and ‘strictly’ earmarked development assistance — in line with current efforts of standardisation in the UN system.21 We performed regression analyses on two different samples, each taking one of the other development assistance flows for comparison.

The bilateral sample includes data for 23 bilateral DAC donors in 75 recipient countries over two monitoring rounds. In all our regressions, we removed variation due to differences across recipients over time. This allowed us to control for events in the recipient countries, such as a change in the incumbent government, which might affect a donor’s ability to promote ownership.

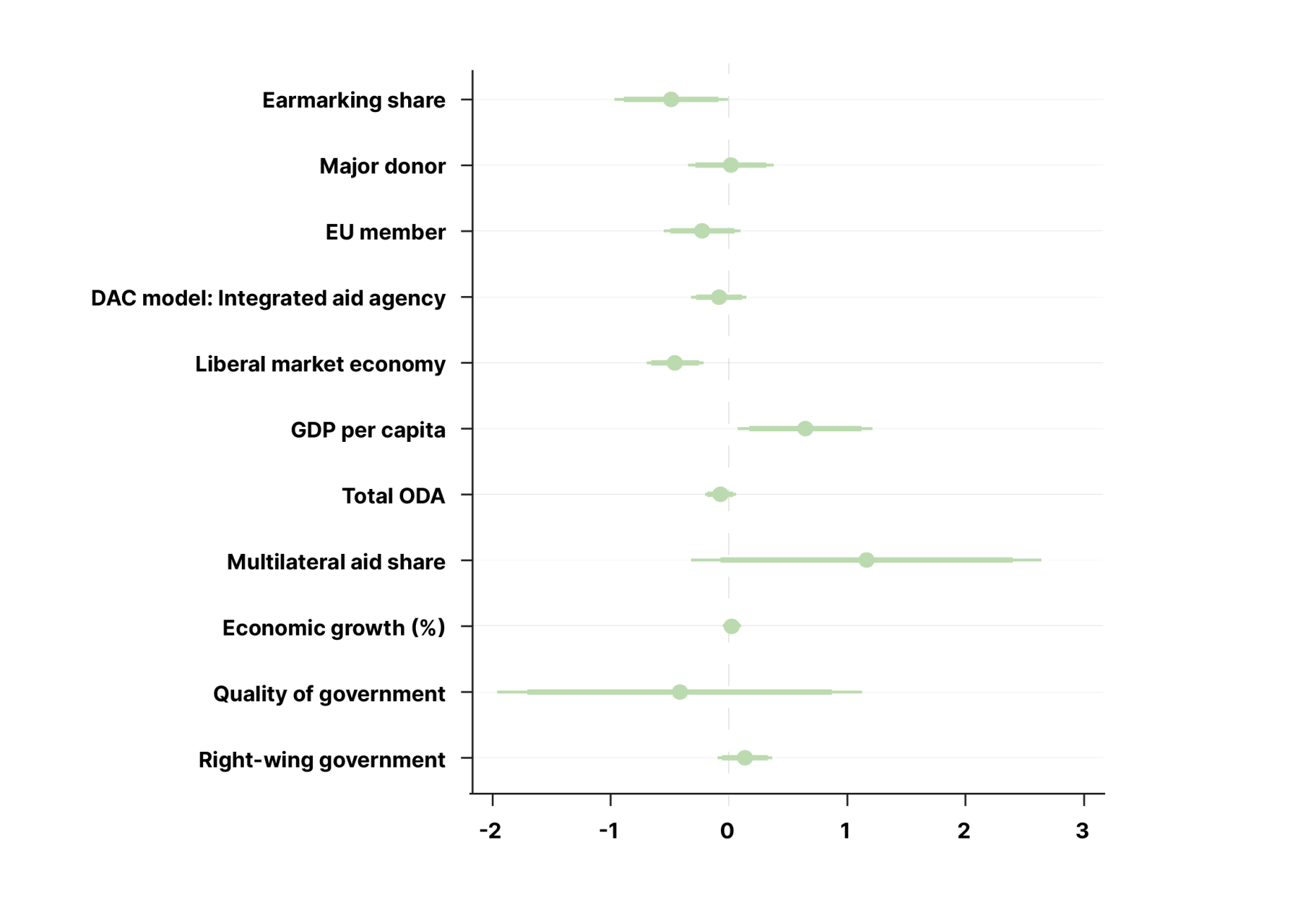

We measured additional features of donors which helped us compare how important earmarking is compared to other political-administrative features for alignment. Figure 4 showed that a greater share of earmarked assistance is related to a lower alignment score. For a given recipient country, a full swing from no earmarking to full earmarking would reduce alignment by half a standard deviation. This is a sizeable effect given that no other donor characteristic appeared to matter more. In fact, most donor characteristics do not significantly affect alignment. Alignment is significantly lower when a donor is a liberal market economy and when its per-capita income is lower, but tends to be higher when a donor channels more assistance multilaterally.

Earmarked development assistance and ownership

Notes: The dots are point estimates, corresponding to the effect of a given covariate on the alignment scores holding all other covariates fixed. Thick lines (90%-CI) and thin lines (95%-CI) are uncertainty estimates for these point estimates.

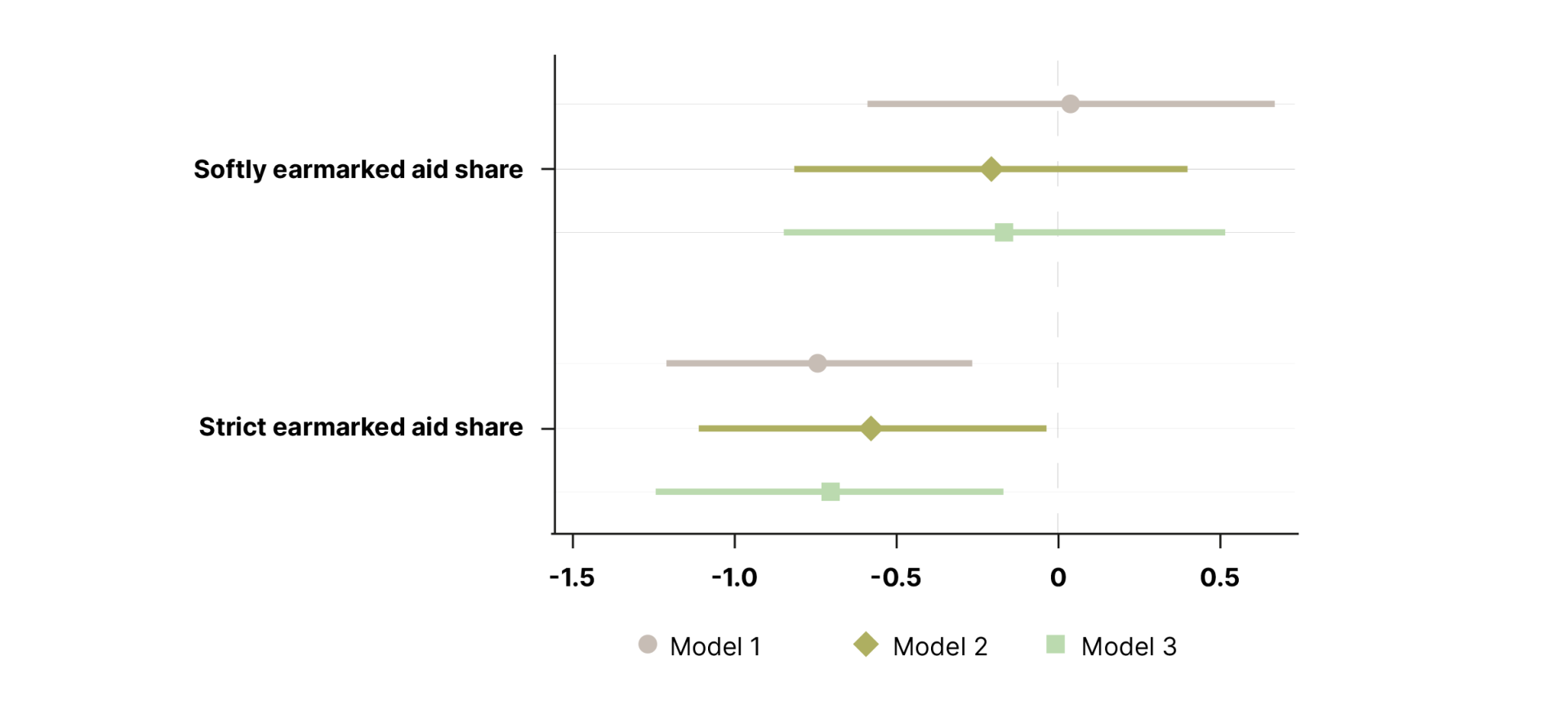

Types of earmarked development assistance and ownership

Notes: The dots are point estimates, corresponding to the effect of a given covariate on the alignment scores holding all other covariates fixed. Thick lines (90%-CI) and thin lines (95%-CI) are uncertainty estimates for these point estimates.

We also examined whether the type of earmarking matters. To that end, we split earmarked aid into ‘softly earmarked aid’ and ‘strictly earmarked aid’. The former indicates support for broad themes or multi-donor funds whereas the latter indicates project-specific earmarking. Figure 5 shows that across different model specifications, strictly earmarked aid has a negative relationship with ownership. In contrast, softly earmarked aid does not appear to affect ownership.22

We also performed the analysis with multilateral donors, comparing how multilateral assistance affects ownership depending on the type of funding that multilaterals provide to recipient countries. The available data cover 18 international organisations in 88 countries across both monitoring rounds. In contrast to core funding, we found that earmarked funding is negatively associated with ownership performance. In further analysis, we confirmed that this result is driven by strictly earmarked funding.

What it means for development practice

Our results have important implications for development practice. It suggests that earmarked assistance is the worst option for ownership, compared to both bilateral assistance and core-funded multilateral assistance.

Donors should therefore support multilateral organisations through core funding. Even if untestable, we believe core funding better enables multilateral organisations to resist donor influence over spending decisions, thereby increasing responsiveness to recipient-led development strategies. Where earmarking is unavoidable to donors, they should channel support through softly earmarked funding. Bilateral development assistance can be an appropriate tool for accomplishing foreign policy goals while upholding ownership if donors work with recipient governments to support their development planning capacity and public financial management systems.

Finally, our analysis reveals that data on ownership is still patchy. To enable robust analysis in the future, development partners should continue to measure their performance against aid effectiveness and extend evaluation frameworks to include monitoring mechanisms for earmarked development assistance.

Endnotes

Malin Hasselskog, ‘What happened to the focus on the aid relationship in the ownership discussion?’, World Development 155 (2022): 105896, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.105896.

University of Glasgow, ‘Resourcing international organizations: How earmarked funding affects aid effectiveness’ project page, https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/socialpolitical/research/research-project… accessed on 25 April 2025.

A notable exception is a study showing how earmarked funding increases the gap between recipient-country preferences and World Bank spending – Mirko Heinzel, , Bernhard Reinsberg, and Giuseppe Zaccaria, ‘Issue congruence in international organizations: A study of World Bank spending’, Global Policy 15.5 (2024): 855- 868, DOI: 10.1111/1758-5899.13413.

We used table DAC3a for ODA allocations by DAC countries (including the EU institutions) and multilateral donors

(https://stats.oecd.org/) and the Earmarked Funding Dataset (Reinsberg, Heinzel, and Siauwijaya 2024) for earmarked aid.

Silke Weinlich, Max-Otto Baumann, Erik Lundsgaarde and Peter Wolff, ‘Earmarking in the multilateral development system: Many shades of grey’, IDOS Studies No. 101, 2020, (Bonn: The German Development Institute, 2020), https://ideas.repec.org/b/zbw/diestu/101.html.

Bernhard Reinsberg, ‘Earmarked Funding and the Performance of International Organizations: Evidence from Food and Agricultural Development Agencies’, Global Studies Quarterly, Volume 3, Issue 4, October 2023, ksad056, pp1–14, (Oxford: Oxford University Press on behalf of the International Studies Association, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1093/isagsq/ksad056.

Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation, ‘GPEDC Excel Monitoring Database, 2020’, online, https://www.effectivecooperation.org/content/gpedc-monitoring-excel-dat… (accessed on 13 July 2022).

These principles of good partnership behaviour include ownership and alignment, focus on results, inclusive partnerships, and transparency and accountability, Global Partnership for Effective Development Co-operation,

‘GPEDC Excel Monitoring Database, 2020’, online, https://www.effectivecooperation.org/content/gpedc-monitoring-excel-dat… (accessed 13 July 2022).

United Nations System Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB), Financial Statistics, 2024, https://unsceb.org/financial-statistics. See also ‘Financing the UN Development System: Time for Hard Choices’, (Uppsala: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, 2019), page 27, https://www.daghammarskjold.se/wp-content/uploads/2019/ 09/financial-instr-report-2019-interactive.pdf.

Control variables were included in the regression but omitted in the graph. Model 1 controls for major donor, EU member, DAC model, and liberal market economy. Model 2 controls for total ODA, ODA/GNI, and the multilateral share. Model 3 includes GDP per capita, economic growth, quality of governance, and right-wing government.