HE Mr Suharso Monoarfa was appointed Minister of National Development Planning, and concurrently Head of the National Development Planning Agency of Indonesia in 2019. His political career started in 2004 after a successful 20 years of experience in business. Over the last two decades, HE Mr Suharso Monoarfa gained prominence serving as Special Staff to the Vice President, Member of the House of Representatives, Minister of Public Housing, and Member of the Presidential Advisory Council of Indonesia.

HE Mrs Judith Suminwa Tuluka, is the Minister of Planning, Democratic Republic of Congo. She is a senior expert in international development with experience in change management and different country contexts. HE Mrs Judith Suminwa Tuluka has over 20 years of national and international experience in the field of democratic governance and peacebuilding, including security governance. Her other experience includes public finance, monitoring budgetary reform, and linkages with civil service modernisation. Before taking up the post of Minister of State in charge of planning, she was Deputy Coordinator responsible for the administrative and operational issues of the Presidential Council for Strategic Watch.

Ms Marie Ottosson has served as the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida)’s Deputy Director-General since July 2017. Prior to this, she was Assistant Director-General at Sida/Director of the Department for International Organisations and Policy support. Ms Marie Ottosson has over 25 years of experience in various positions with the Swedish government. Other roles previously held include Deputy Head of Mission for the Embassy of Sweden in Vietnam, Senior Auditor with the Swedish National Audit Office and working in Luxembourg as an Auditor for the European Union for almost seven years, auditing the European Commission.

Mr Vitalice Meja is a founding member and a former Co-Chair of the Civil Society Organization Partnership for Development Effectiveness, an open platform that unites civil society organisations from around the world on effectiveness issues. He is also Executive Director of ‘Reality of Aid Africa’, a pan-African network focused on poverty eradication through effective development cooperation. A key purpose of the organisation is strengthening the involvement of African civil society organisations in informing policy issues related to the international aid architecture, as well as issues around development cooperation. Mr Vitalice Meja has many years of experience in development policy advocacy, as well as in research at the national, regional and international level on financing for development, debt and official development assistance with both governments and multilateral bodies.

Introduction

The United Nations marked its 75th anniversary in 2020 – signifying three generations committed to working toward peace, development and the spread of human rights. The same year, the most destabilising pandemic in over a century brought parts of the world to a standstill, providing a dramatic example of global goods, global ‘bads’ and the extent of international coordination needed to address some of the greatest threats to peace and prosperity. The experience of the COVID-19 pandemic brought a whole new focus to multilateralism and has resulted in a number of efforts to strengthen multilateral solutions more broadly. Already in 2020, the UN Secretary-General had developed the initial thinking for Our Common Agenda: an ‘agenda of action’ to strengthen multilateralism, leading to the ‘Summit of the Future’ due to be held in 2024.

In 2022, the International Peace Institute released the pilot report of its new Multilateralism Index1, and earlier this year the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Advisory Board (HLAB) on effective multilateralism released sweeping proposals for a new ‘blueprint’ on reinvigorating global governance.

The Global Partnership for Effective Development Co- operation (GPEDC) – the primary multi-stakeholder initiative advancing development effectiveness for the 2030 Agenda – made its own contribution to this work in 2022 (as the GPEDC marked its tenth anniversary) in the form of the ‘A Space for Change’ report.2 This is a study of partner perceptions of the UN and, to a lesser extent, the broader multilateral system, taking the four principles of effective development cooperation (country ownership; inclusive partnerships; transparency and mutual accountability; a focus on results) as an analytical lens.

The report’s authors collated the study findings, which suggest there is much that partners value in the UN development system, not least in terms of aligning development cooperation to the effectiveness principles for more sustainable development outcomes. But the findings also show that the system’s effectiveness is shaped by how partners support the system – an important reality that has been highlighted in reports over many years.

Two further findings stand out:

- partners to the UN value the UN development system as a space for effectively navigating and managing their own, and others’, competing policy priorities – although treating the system as a service-provider delivering ever-higher volumes of earmarked contributions undermines this crucial role; and

- efforts such as the Common Agenda and Summit of the Future are ultimately dialogues about how we work together for a more inclusive and sustainable future. Also, GPEDC’s effectiveness monitoring exercise, re-launched in 2023 and designed to gauge partners’ progress on the effective-ness principles, is a critical contribution to those dialogues.

Using the effectiveness principles as an analytical ‘lens’

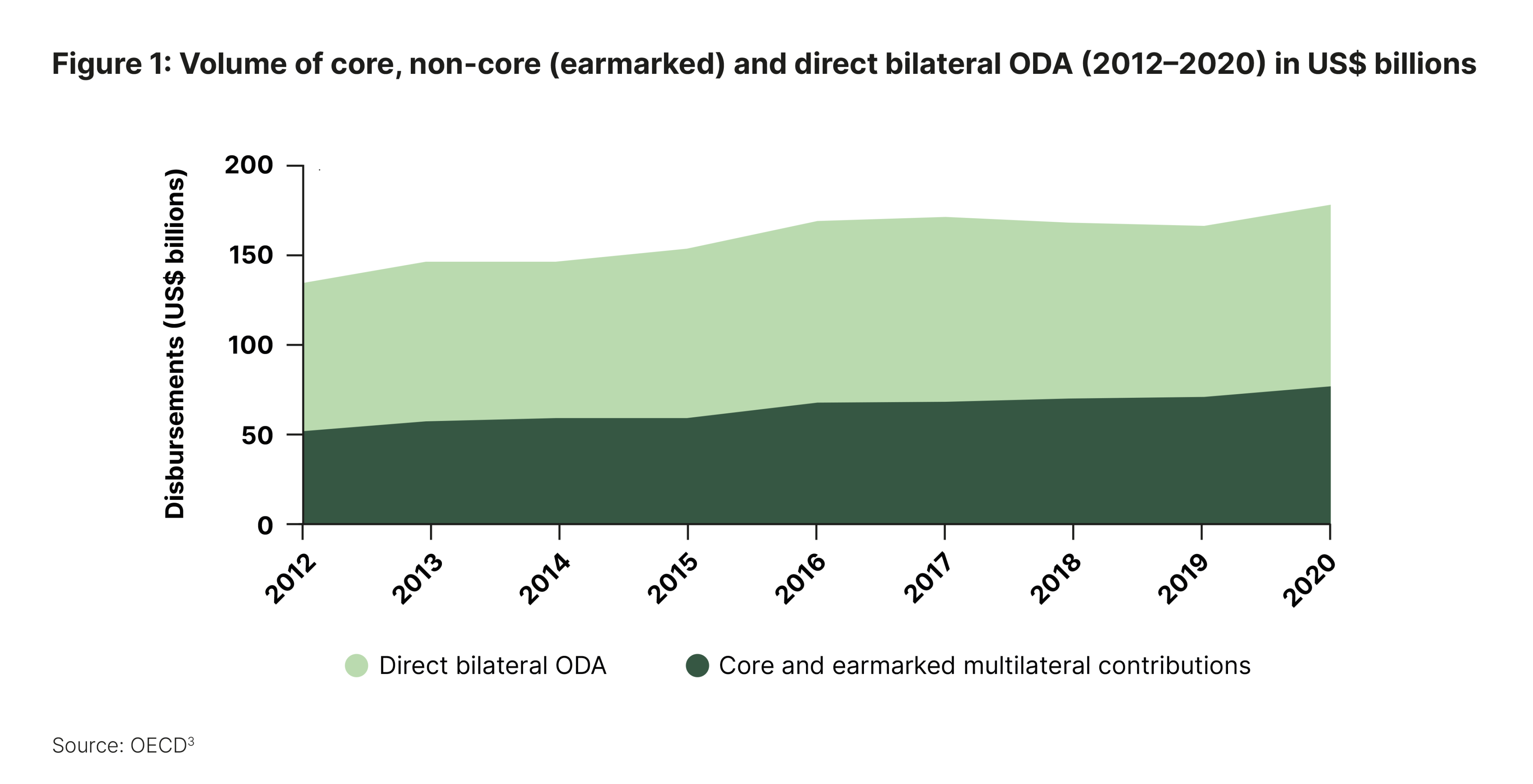

The ‘A Space for Change’ report did not have to look far to establish a basic sense of confidence in the UN development system: While the vast majority of funding and financing for development through the UN is voluntary (ie not binding/assessed based on the fact of membership), overall contributions to the multilateral system continue to grow (Figure 1), both in real terms and as a share of total official development assistance (ODA) – increasing from 39.1% of ODA in 2012 to 43.2% of ODA in 2020.

When development partners and donors were surveyed on the important factors for allocating funding to the UN, more than two-thirds (67% plus) cited its transparency, alignment to national priorities and ‘whole-of-system’ inclusive approaches (good proxies for the principles of ‘transparency’, ‘country ownership’ and ‘inclusive partnerships’) as ‘very important’ (Figure 2).

In addition, GPEDC’s own data from the 2018–2019 moni-toring round shows how the UN development system can often be more effective in its delivery than bilateral partners:

- close to 60% of UN partners use government data and monitoring systems, compared to 50% of development partners overall; and

- 80% of UN partners undertake final evaluations with governments, compared to 59% of development partners overall.

But, in keeping with a consistent theme with the Financing of the UN Development System report, much of this performance is inherently linked to how the multilateral system is itself supported by partners: one of the few areas where the UN development system did not perform better than other development partners was on ‘predictability of aid’ – a direct consequence of the UN development system’s annual funding horizons.

Partner perceptions and trade-offs

These initial findings were supported by additional interviews, conducted by GPEDC’s ‘effective multilateralism’ working group in 2022, which brought together 18 organisations (including six Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development-Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) members, non-governmental groups and other international organisations).

They all stated that the UN development system, and multilateral organisations more broadly, are often effective actors. Set against the effectiveness principles, they found that the UN can be more effective than bilateral partners acting alone. More specifically, in terms of the each of the four principles – namely country ownership, inclusive partnerships, transparency and mutual accountability and a focus on results – partners saw the UN development system as helping them advance their goals.

In terms of national ownership, interview discussions backed quantitative data findings (see above; from sources like the UN’s own Quadrennial Comprehensive Policy Review reporting, and GPEDC monitoring data) that the UN and other multilaterals were often better aligned with local efforts than other partner-types – indeed, this was perceived by development partners as one of the top three reasons for working with multilaterals.

But we also saw that national ownership means different things to different actors, and that a ‘classical’ reading of ‘government-of-the-day’ buy-in is increasingly seen as too limited. Indeed, some development partners, even in the same context, pursued national ownership differently on different topics. One donor based in Kinshasa, for instance, was happy to fund the government on-budget for service provision, but not for other types of more sensitive programming, where they instead preferred UN-led country-programmes developed through extensive consultations.

On mutual accountability, there was clear recognition of UN standards on transparency and reporting across interviewees (see, for instance International Aid Trans-parency Initiative results). Definitional questions, however, remain – not least in terms of accountability to whom?

Development cooperation necessarily operates at a delicate junction – particularly in terms of central political and distributional questions, it is often conducted through the prism of foreign policy, where governments have historically acted without the close scrutiny of civil society or auditors, let alone the parliaments they are beholden to. Again, the UN, while not ‘resolving’ these questions as such, was seen by respondents as helping ground programmes and policies in the broader polity, for example through processes like the formulation of the Cooperation Framework.

In terms of focusing on results, there was a clear under-standing of the goals the UN is working toward, not least in terms of supporting governments’ ambitions on the 2030 Agenda, and responding to sudden-onset crises, such as COVID-19. Here, attention focused on the UN development system’s normative role: respondents proposed that their gender programming will be stronger with UN Women or simply preferred to navigate more politically complex landscapes within a broader partnership.

While UN agencies were viewed as helping to convene partners around development policy, globally and at country level, inclusive partnerships remain less developed. Some argued development has never been more inclusive in terms of general awareness of and technical application to more marginalised groups. And yet, as we consider our understanding of national ownership and accountability, key institutions of the state – from parliaments to auditors – as well as civil society, are often missing from development partnerships and priority-setting exercises.

Over the course of discussions, however, distinct themes began to emerge among respondents in terms of expec-tations of the system: unanimously among development partners and near-unanimously among other partner-types. These were:

- country ownership and access;

- partners’ own objectives and policy agenda; and

- internationally agreed norms and values.

Why would partners seek to pursue these objectives, specifically through the UN? And to what extent are they coherent with one another?

Thomas G. Weiss and others have done extensive work interpreting the UN – and the broader multilateral system – as a ‘policy space’ for achieving outcomes and objectives that would not otherwise be possible working individually. This policy space is created via collective action: de-risking action by individual actors as the potential risk-burden is shared.7

This UN policy space is often understood as having three distinct aspects: 1) as a convening space, bringing together Member States in an ongoing dialogue; 2) as a corps of expertise for implementing decisions reached within that space; and 3) as a repository of norms, embodying the values that have been agreed upon, from the importance of national sovereignty to human rights.

As the examples of national sovereignty and human rights suggest, some of these values may come into conflict, underscoring the role of the system, in terms of partners’ perceptions, as both a space for policy formulation and a space for navigating – as much as resolving – the tensions between fundamental values and objectives.

In order to explore this role, GPEDC’s analysis borrowed a concept more often used in economic research: a ‘trilemma’, where the pursuit of two objectives precludes a third. Placing our three emerging themes – country ownership and access; partners’ own objectives; and international norms – into a ‘trilemma’, it soon becomes apparent how these objectives can sometimes conflict with one another. It also highlights how the system often works as a policy space for navigating, managing and even minimising the trade-offs between sometimes conflicting objectives. A recent example of this kind of policy navigation, by way of the UN, can be seen in richer countries seeking to protect patents on COVID-19 vaccines while at the same time investing in a global administrative architecture such as the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) (etc) through the World Health Organization and UN Children’s Fund to otherwise expand access to them.

Lessons: Compacts, humanitarian funds, financial institutions and country-level data

What is expected of the UN development system, then, is not just a set of organisations that perform relatively robustly, or even a dedicated policy space for development cooperation on issues of the day. Rather, and in addition to these, it is a space for managing the trade-offs between central, and sometimes competing, values and objectives. This is a lot to expect when roughly three in every four dollars invested is earmarked to a specific project.

All development-partner respondents to GPEDC’s work were aware of the Funding Compact, adopted in 2019 to put development financing on a surer, more robust, footing. Core funding, pooled funding and multi-year commitments all featured prominently in discussions, also recognising the three indicators furthest from being achieved. The Compact, however, can still be an agreed basis for working toward more effective development cooperation: leveraging the system for inclusiveness and ownership at a country level, with a focus on sharing (not project-level) results and accountability through system-/organisation-level reporting.

The GPEDC’s work also explored learnings from other development cooperation channels, including humanitarian spending and the operations of financial institutions. The Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs’ pooling and standing-capacity instruments, nascent forecasting efforts, and development partners’ own innovations around separate credit frameworks for development and humanitarian spending (so one is not at the direct expense of the other), with separate frameworks/instruments for ‘nexus’ activities, are all examples of how financing can be done differently – and almost certainly more effectively – than is currently the case.

Development banks, meanwhile, offer their own opportunities for learning. A 2022 Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN) report on multilateral COVID-19 pandemic response dedicated a section to integrated responses involving financial institutions, including how the UN development system could connect better with development banks and the International Monetary Fund.9 As banks, they are typically dealing with OECD-DAC country treasuries, rather than development agencies, arguably giving them greater voice and purchase over policy. Moreover, while the shareholder model entrenches donor interests in some ways, it also creates a clearer fiduciary responsibility, with scope for multi-year/rolling investments. This is the case even for those partners who are otherwise unable, for ostensibly legislative reasons, to make multi-year contributions to the UN development system.

Finally, and no less important than the learning opportunities identified above, there is the work of GPEDC itself, which includes taking responsibility for assessing the alignment of country-programmable aid with the effectiveness principles at a country level, thereby driving political commitment and working towards behaviour change for more effective cooperation and more sustainable development outcomes.

The year 2023 marked the re-launch of GPEDC’s monitoring exercise, following progress reports in 2014, 2016 and 2019. The updated exercise supports more sustainable development outcomes through a virtuous cycle of inclusive dialogue, collective accountability, tracking results and agreeing on actions.

Since the last monitoring round in 2018–2019, at least 45 countries have used the results in their development planning processes, all ten OECD-DAC ‘peer reviews’ under - taken have reflected the results, and at least 55 reports have cited country-level evidence from the exercise in order to gain a clearer view of what works and what doesn’t.

The system of the future

It is worth taking a moment to reflect on what, based on the above, is most effective about the multilateral space. It is a protected sphere for shared action that creates options, alternatives and even ways of saving face that can be used to navigate some of the toughest policy challenges today, from climate crisis to war. More than this, it is the very fabric of our solidarity across nations, and a mutual support and protection network.

These and other ideas, along with recommendations, are explored further in ‘A Space for Change’. Moreover, with the re-launch of the monitoring exercise, GPEDC is continuing to invest, alongside its partners, in country-level insights into real accountability around development cooperation flows, as well as the roles different development actors – including multilaterals – can play in making cooperation more effective. Though the exercise is led by partner country governments, it will continue to generate a wealth of data on development partners, including the UN development system. In the 2018–2019 round, 28 UN entities reported across 73 UN country teams, representing over US$ 6 billion in country-programmable development cooperation. The UN development system, in convening partners around development goals as it does, is ideally placed to help drive such monitoring efforts.

Shortcomings are as valuable as successes in a system committed to learning and improving. The Summit of the Future is about thinking and acting on behalf of future generations: a commitment to learn from today, to leave a better tomorrow.10 Encouraging partners to engage in GPEDC’s monitoring exercise – to better understand how we are working together and what we can improve – is a contribution to this same legacy and an investment in the next 75 years.

Endnotes

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Multilateral Development Finance 2022 (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1787/9fea4cf2-en.

UN General Assembly, ‘Quadrennial comprehensive policy review of operational activities for development of the United Nations system’, A/RES/75/233, 30 December 2020, https://undocs.org/a/res/75/233.

The full list of partners who participated in the work consists of: Albania, Center for Global Development, Colombia, CSO Partnership for Development Effectiveness, Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, Germany, Inter-American Development bank, Inter-Parliamentary Union, INTOSAI Development Initiative, OECD, Peru, Republic of Korea, Sweden, Switzerland, UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office, UNDP, UK, World Bank Group. Survey and interview work was undertaken May–July 2022.

Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund Office (UN MPTFO), Financing the UN Development System: Time to Meet the Moment (Uppsala/New York: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation/UN MPTFO, 2021), www.daghammarskjold.se/publication/unds-2021/.

Multilateral Organisation Performance Assessment Network (MOPAN), ‘More Than The Sum of its parts?: Multilateral Response to COVID-19’, MOPAN, 2022, www.mopanonline.org/analysis/items/lessonsinmultilateraleffectivenessco….