Pedro Conceição is Director of the Human Development Report Office at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and lead author of the ‘Human Development Report’ since 2019. Previous positions held include Director, Strategic Policy, at the Bureau for Policy and Programme Support; Chief Economist and Head of the Strategic Advisory Unit at the Regional Bureau for Africa; and Deputy Director and Director of the Office of Development Studies. He has written extensively on financing for development, global public goods, inequality, and the economics of innovation and technological change as well as development. Prior to joining UNDP, Pedro Conceição was an Assistant Professor at the Instituto Superior Técnico, Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal, teaching and researching science, technology and innovation policy. He has degrees in Physics from Instituto Superior Técnico and in Economics from the Technical University of Lisbon and holds a doctoral degree Public Policy from the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin in the United States.

Introduction

The world since 1990 has certainly been turbulent. In many contexts societies faced significant events with implications for the lives of millions of people. On another level there is also the proliferation of internal violent conflicts and the global financial crisis in the mid-to-late 2000s caused much upheaval.

A turning point in the evolution of human progress

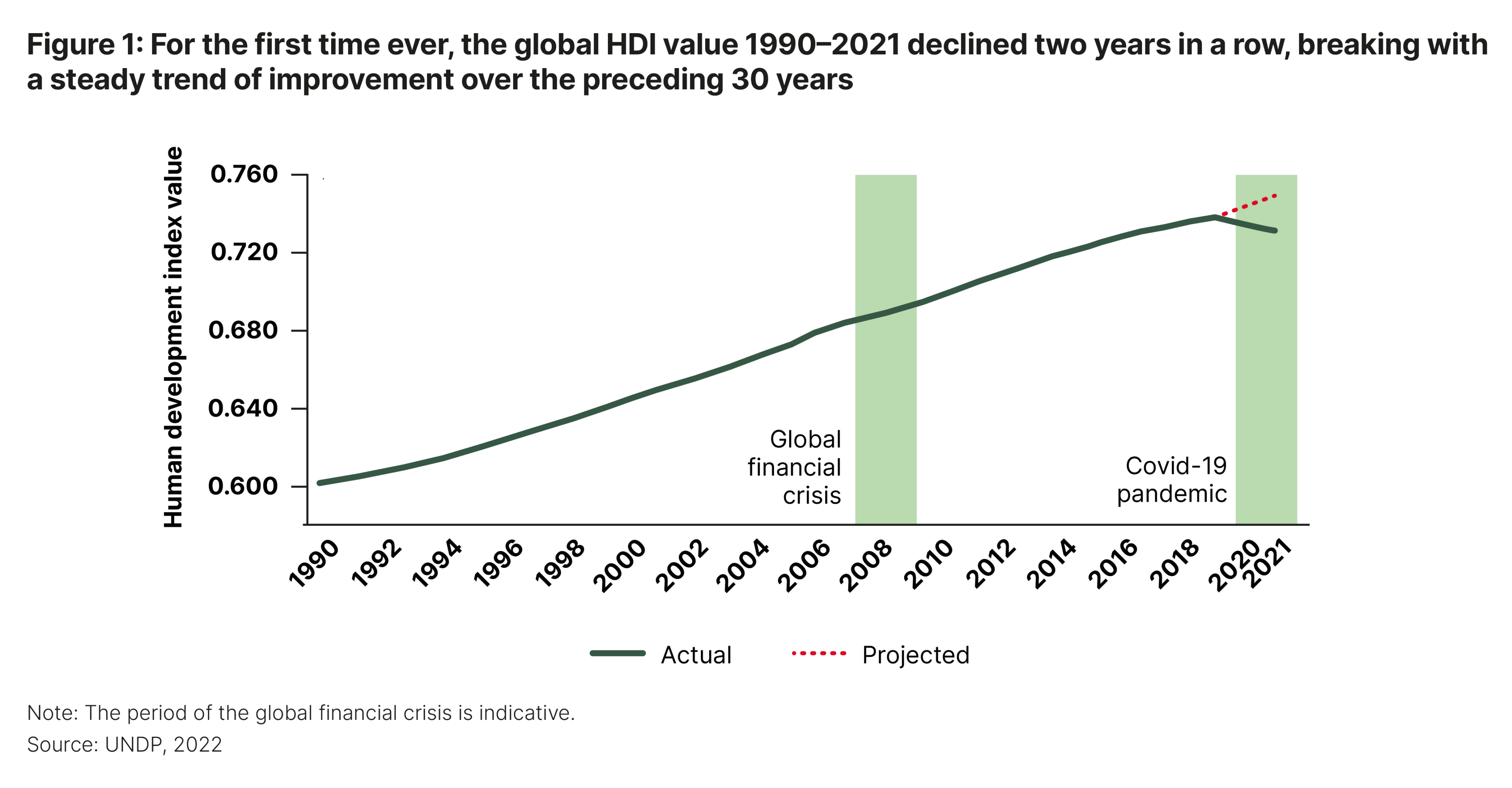

Yet, looking at the evolution of the global human develop- ment index (HDI)1 since the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) first started computing it in 1990, one does not see much volatility, but rather a steady march of improvement until 2019. The data shows that the HDI suffered an abrupt decline for the first time ever, two years in a row, during 2020 and 2021, as expressed in Figure 1.

A decline in the HDI for a few countries and over some years should be no surprise, given the upheaval that many parts of the world confronted since 1990. What lies behind the decline in global HDI and was it concentrated in a number of countries or regions?

Up until 2019, about 10% of countries in the world witnessed a decline in their HDI in any given year, a percentage that rose to about 20% during particularly turbulent times (during the global financial crisis). In 2020–2021 over 90% of countries in the world suffered a decline in their HDI, as shown in Figure 2.

Even though the decline in the HDI was fairly universal across countries, it was more persistent for countries with low, medium and high levels of the HDI. A majority of countries in these categories saw a decline into 2021, while only one third of very high HDI countries did as Figure 3 indicates.

Much of what preoccupies national policymakers and the international community at the moment can be traced to the impact of and response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Concerns associated with the aftermath of the pandemic range from inflation to the debt burdens of many low- and middle-income countries; from the prospects of a slowdown in economic activity to deteriorating trends on extreme poverty, food insecurity and forced displacement. A set of challenges compounded by heightened geopolitical tensions and the intensification and spreading of violent conflict, including the war in Ukraine.

Moreover, the current context is engendering a situation in which weather, economic, and social and geopolitical volatility exacerbate not only some inequality, but also insecurity. The ‘Human Development Report 2021/22’ found that six out of every seven people feel insecure, and that these perceptions of insecurity have been on the rise in many countries.

In addition, it found that higher insecurity is associated with, on the one hand, lower generalised trust and, on the other, people being attracted to the extremes of the political spectrum. Thus, trust is now the lowest on record and political polarisation is on the rise in many countries. Two of the key ingredients that can encourage people to come together to address shared challenges.

Interdependence brought about by globalisation is likely to deepen as we move deeper into the Anthropocene

There are two important aspects to bear in mind in the context we confront. First, that people around the world are highly interdependent. This manifests in multiple ways, including for example, the war in Ukraine causing volatility in international prices of food and energy, as well as a threatening food insecurity crisis for vulnerable populations around the world. Another illustration pertains to the global value chain disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the concerns over contagion of financial instability or debt distress. And it extends to our digitally connected world that allows for instantaneous sharing of information across practically all of the 8 billion people living on Earth today. Interdependence is the result both of policy choices – in terms of how much countries allow for the flow of people, goods and services, finance and information – and technology, which determines the cost, speed and ease of international flows, as well as the ways in which these two factors interact. Even though policy can constrain cross-border flows, technology may make that hard, particularly given that many people can easily catch a jet flight or how anyone can share information virtually via digital networks.

Second, the fact that we, and future generations, share a planet undergoing dangerous changes for people and other forms of life. These threatening planetary changes, which are the result of human action as populations, consumption and production expands, are having unprecedented impacts on planetary processes. Climate change and the destruction of the integrity of many ecosystems are manifestations of this.

So dramatic and unprecedented, both in human history and the geological timeline, are these anthropogenic changes to planetary processes that Earth-system scientists, geologists and many others are referring to a new geological epoch: the Anthropocene.2

Policy choices or technology can make little difference in insulating a country from confronting climate change or the consequences of the extinction of a species. As human pressures on nature increase, so too does the frequency of new and re-emerging zoonotic diseases, of which COVID-19 was likely yet another case. Thus, what we went through during the pandemic may be less of a case of a once in a hundred-year event, but more a reflection of what the world will be confronted by as we go deeper into the Anthropocene.

The salience of global public goods will likely be heightened in our Anthropocene future

Interdependence is not new, even if it has intensified, deepened and widened since the 1980s, as when what is sometimes referred to as a new era of globalisation unfolded.3 This has led to recognition of the importance of cross-border spill overs. Mitigating the negative conse-quences of some of these spill overs (the spread of a new virus or a financial panic across countries) or harnessing the potential benefits of others (the diffusion of scientific and techno logical breakthroughs or the peaceful means of resolving disputes) can be described as global public goods (GPGs).4

Global public goods are not merely things that are desirable. There are many globally desirable things which are not GPGs because they lack two distinctive characteristics. Described as partial or full non-excludability and non-rivalry benefits that extend to people living in many countries and potentially to everyone at the global scale.5 As we go deeper into the Anthropocene, and as science and technology continue to race ahead, GPGs are likely to acquire heightened salience in shaping people’s wellbeing and opportunities.6

Examples of GPGs include the early identification and containment of new and re-emerging zoonotic diseases; mitigating climate change; containing the spread of financial crises; allocating geo-stationary orbits to satellites; maintaining peace; and fostering cybersecurity, amongst many others. Some of which GPGs cannot even be envisioned, as we do not yet have the knowledge to identify them.

For example, it is only recently that science and detection technologies made it possible to document the depletion of the ozone layer or establish the anthropogenic cause of climate change, or we are yet to make the choices that would create new GPGs.

Dispelling three myths about global public goods

It might be argued that a GPGs frame is redundant because the world can address concrete challenges as they emerge. But this logic of tackling each global challenge on its own specificity would be a missed opportunity.

Climate stability, fair and efficient international trade and financial systems, communicable disease control and peace may seem like disparate aspirations. But if, at their core, they have the characteristics of global public goods – as is argued here – then using a GPGs lens would allow for cumulative and lateral learning about features and patterns that may be shared across a wide range of issues, without the need to try to create solutions from scratch separately for each challenge. Moreover, a GPGs lens would enable the realisation that many can be created or, at a minimum, to recognise their existence or emergence.

Sometimes a GPGs frame is portrayed as being harmful. There are three reasons that are occasionally invoked. It is important to examine these concerns, but also see how they can be addressed by drawing on much of the analytical and empirical work that has been done on GPGs over the last 20-plus years. The first is the facile but wrong reasoning that GPGs work just like any national public good, which are typically provided domestically by governments. Indeed, there is much that one can learn analytically from the theory of public goods, but the key lesson when it comes to GPGs is that there is a plethora of institutional arrangements that exist and many others that could be designed and implemented – that would enhance the provision of GPGs without any need for any supranational entity.

Availability or access to GPGs depends on multiple layers of agents, from individuals to organisations such as firms, civil society, philanthropic organisations or universities. The most important agent is sometimes either a country or collectives of countries, which occasionally gain expression in the form of multilateral institutions. But all layers interact across and within each other. When governments are the key agents for a specific GPG, then the analogy with domestic public goods is particularly unhelpful, because domestic public goods imply coordination or cooperation by millions of agents, whereas for GPGs it may be a few or, at most, a couple of hundred of countries.

Moreover, given that GPGs involve a much wider geographical range than national GPGs, when countries are the key agents involved in provision that implies that there is a need to consider different capabilities to contribute, and concerns of fairness are paramount because no country can be coerced to contribute. This poses significant challenges, at least for some types of GPGs, but the solutions to reason through the analogy of national public goods, given that some institutional options are simply not feasible, but rather to understand why the prognosis for the provision of different GPGs varies and devise specific institutions and mechanisms to improve the provision of GPGs. This is yet another reason why having a clear GPGs analytical frame is helpful.

A second, somewhat related, concern is that a GPGs lens implies limiting the autonomy of countries. Nothing could be further from the truth, for it is precisely the opposite. When negative cross-border spill overs are better contained and positive spill overs amplified, autonomy and policy space are enhanced. While this should be almost self-evident from the non-rival and non-excludable nature of GPGs, the recent COVID-19 pandemic and its repercussions provide a striking illustration. Failures in GPGs provision harm the autonomy of countries, with the burden falling more heavily on countries and population groups that are already more vulnerable and have less resources. Just witness how many low- and middle-income countries are now saddled with debt burdens that limit their development prospects.

A third concern is that consideration of GPGs implies the diverting resources from official development assistance (ODA). Setting aside the fact that this is no reason to ignore the reality of the need to manage GPGs in our interdependent world, enhancing the provision of GPGs often gives even more reason for resources to flow to low- and middle-income countries. This is particularly the case for GPGs that are similar to communicable disease control, where the overall level of provision is determined by the country with the least capability. Thus, investment in disease surveillance in low-income countries is the only way to enhance the provision of this particular GPG.

Individuals and countries may choose to channel resources to countries in need for a variety of reasons, from being altruistic to having a moral sense of duty and responsibility. But these motivations are not crowded out by the recognition of GPGs, particularly when GPGs are associated with joint products that benefit low- and middle-income countries as well as enhancing the provision of GPGs. One such example is investing in renewable energy in low-income countries to mitigate climate change, which also enhances local access to electricity. At the same time, it is important to recognise that GPGs often require new and additional resources, and it is crucial that these are not siphoned off from flows that have been provided with a different motivation, such as official development assistance.

Not all global public goods are created equal

‘Created’ may seem like an odd word to use. Aren’t GPGs things that just exist out there, with some inherent characteristics? To some extent, but this alone does not fully determine what is or is not a GPG.

Just consider a military alliance in which all members commit to defend any member that suffers a military threat from outside the alliance. Suddenly, a transnational public good is created out of thin air which is the deterrence against military aggression that is shared by all alliance members. In other words, institutions matter and can influence what is or is not a GPG, and may even create some from scratch. And these goods matter in a very specific way, with institutions determining the incentives in production or consumption that shape the degree of excludability.

Technology also matters. For instance, currently media content is largely non-rival because someone watching a television show does not detract from anyone else also enjoying or at least watching it. With television and radio broadcasts, content can be picked up by anyone with a device equipped to tune to the right frequency, so it was largely non-excludable as long as there is access to a media playing device. But cable television made access to content fully excludable, while streaming television has provided yet another evolution in how technology shapes access to media content. This has implications for which financing model is used to produce content: one that can be predominantly based on an advertising revenue model for broadcast television, or one that is based on subscriptions for cable television and streaming platforms.

In evaluating what can be considered a GPG, intrinsic char ac - teristics are often determinant. It is hard to see how either institutions or technologies would change the reality that greenhouse gases from every country mix in the atmos-phere, in the aggregate and over time, leading to climate change.

As a general rule, however, GPGs can be considered to emerge as a result of the interplay between institutions and technology – both of which are the result of social choices – and the intrinsic characteristics of the good in question. This implies that there are a myriad of ways in which GPGs can be shaped by social choices, but there are two aspects that require particular attention because they can point to patterns that are shared across a wide range of GPGs that can inform strategies enhancing their provision.

In other words, one might not need to start from scratch when thinking about how to provide every GPG if it would be possible to classify them according to some shared characteristics, along with the institutional arrangements that would enhance the provision of all GPGs sharing those characteristics.

For a long time, all GPGs were seen as being like climate change, with the level of provision of the GPG determined by the sum of individual contributions from of every country on the planet.

The aggregation technology for this type of GPG that is the way in which individual contributions are combined to determine the overall level of provision, is simply a summation of all the individual contributions, which are indistinguishable from one another. This type of summation GPG tends to be associated with dilemmas between the motivations of each member of a collective to contribute, and the expectations about the will of others. Even if one member contributes all it could, the overall level of provision of the GPG will be determined also by how much all the others pitch in.

When everyone is trying to figure out in isolation how much others would contribute it can be expected to result in an outcome where the sum of the individual contributions is lower than what can be collectively desirable and or feasible. Perhaps because one is concerned that someone else might take a free ride, that lowers the incentive for individual contributions to the collective good.

In the case of summation public goods, institutions need to be designed to break or mitigate this social dilemma. This has been challenging for climate change, but successful in addr essing the causes of the thinning of the ozone layer, thanks to a range of economic, social, political, and technological factors that made that outcome feasible.7 These included having a readily available technological alternative to chlorofluoro carbons (CFCs) that multinational firms had an interest in promoting, as well as the strong incentive of countries in higher latitudes, many high-income countries, to stave off the risk of skin cancer in their populations, leading to an agreement to channel resources to low- and middle-income countries.

Rather than exploring in detail the mechanism design, the purpose here is to note that in addition to summation public goods, there are other aggregation technologies. There are, in fact, a myriad possible aggregations, but in addition to summation, there are two that are particularly important.

The first of these as previously mentioned, is disease surveillance, which belongs to a category of GPGs for which the aggregation technology is the weakest-link with the overall level of provision determined by the country with the least capabilities. The incentive in such cases is to reduce inequalities and channel resources to the country or countries with the least capabilities. This was how smallpox was eventually eradicated, even at the height of the Cold War.

The second is when the overall level of provision is deter-mined by only a single country or agent, usually the one with the most capability and motivation. This type of GPG, called ‘the best shot’, includes scientific breakthroughs and, potentially, the motivation of a single country to stave off an asteroid bound for Earth. Here, again, it may be in the interest of a single or a few countries to provide the GPG on their own, with some high-income countries already conducting experiments to divert the orbit of asteroids.

Harnessing global public goods in the Anthropocene: Inescapable and potentially motivating of greater solidarity

This article has argued that globalisation, technological change, and the new reality of the Anthropocene are likely to make GPGs more relevant than ever looking at the future. Most of the emphasis of current development and financial institutions is premised on the idea of supporting and enhancing domestic policies. Clearly, this is a crucial priority, but as the experience of the COVID-19 pandemic dramatically demonstrates, even the countries with the most resources and arguably the highest policy capabilities struggled with the responses. What’s more, those with the least capabilities are now saddled with debt and other constraints in their policy and fiscal space.

Clearly, it is time to supplement the focus of development cooperation on domestic action with commensurate attention to shared challenges, both to mitigate negative cross-border spill overs and harness the potential of positive spill overs. This matters crucially also for the expansion of human development, which has been pursued primarily by looking at domestic policies, as will be explored in the 2023 Human Development Report, that will draw from and expand some of the arguments in this article. Important though domestic policies are, the expansion of human development in the Anthropocene is going to depend also, and perhaps more and more as the experience with the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted earlier, on our ability to address shared global challenges.

A GPG lens can provide a useful analytical frame to guide and inspire policy, institutional design and financing. The world is trying to address challenges one by one as they are thrown out at us, from national governments to international organisations like the UN and the international financial institutions. As we go deeper into the Anthropocene, it would be a missed opportunity not to use this lens to address the challenges associated with our deep interdependence with one another and our planet, and perhaps even leverage the provision of GPGs to mobilise action towards greater solidarity.

Endnotes

The HDI combines indicators for standards of living and achievements in health and education, providing for a broader measure of wellbeing than gross domestic product. For more details, see Pedro Conceição, Milorad Kovacevic and Tanni Mukhopadhyay, ‘Human development: A perspective on metrics’, in Barbara Fraumeni (ed.), Measuring Human Capital (New York: Academic Press, 2021); and United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), ‘Human Development Index (HDI)’, https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/human- development-index#/indicies/HDI. See also Pedro Conceição et al., Human Development Report 2021/22: Uncertain Times, Unsettled Lives: Shaping Our Future in a Transforming World (New York: UNDP, 2022), https://hdr. undp.org/content/human-development- report-2021-22.

For a review of the evidence and debates around the notion of the Anthropocene, and what that means for development, see UNDP, Human Development Report 2020: The Next Frontier: Human Development and the Anthropocene (New York: UNDP, 2020), https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/hdr2020pdf.pdf.

Pedro Conceição and Ronald U. Mendoza, ‘Identifying High-return investments’, in Inge Kaul and Pedro Conceição (eds), The New Public Finance: Responding to Global Challenges (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006). See also, for instance, Inge Kaul et al., ‘Why do global public goods matter today’, in Inge Kaul et al. (eds), Providing Global Public Goods: Managing globalization (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003).

Full non-rivalry means that someone benefiting from a GPG does not take away from what is available for everyone else to enjoy. Full excludability means that the benefits are available to everyone without the possibility of excluding anyone. For a recent elaboration of these concepts and review of GPGs, see Wolfgang Buchholz and Todd Sandler, ‘Global public goods: A survey’, Journal of Economic Literature 59/2 (June 2021), pp. 488–545.