Nada Al-Nashif was appointed United Nations Deputy High Commissioner for Human Rights in 2019, and has over 30 years of experience within the UN as an economist and development practitioner. Al-Nashif served as Assistant Director-General for Social and Human Sciences at UNESCO (Paris), as Regional Director of the International Labour Organization’s Regional Office for Arab States (Beirut) and at the UN Development Programme in various headquarters and field assignments.

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations.

On 1 April 2022, the Human Rights Council (HRC) concluded the longest session it had held since being established in 2006.1 The session took place against an exceptional backdrop of events that placed the HRC at the heart of multilateral diplomacy, at a time when other intergovernmental bodies were in stalemate. In response to rapidly evolving developments following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the HRC – taking upon itself a mandate for accountability – called for immediate de-escalation and respect for international humanitarian law.

The urgent debate of 3–4 March 2022 at the 49th session of the HRC led to the formation of an independent international commission of inquiry mandated with investigating alleged human rights violations and abuses, violations of international humanitarian law, and related crimes in the context of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine (with 32 votes in favour of the resolution, 2 against and 13 abstentions).2 Streamed live on the HRC’s Twitter account, the debate pulled in 3.7 million viewers, with its ensuing resolution re-tweeted over 4,500 times. The resolution was unique in being the first ever to call for an investigation of a permanent member of the Security Council (ie Russia).

Centrality of protection and the Human Rights Council

Since 2014, the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) has presented close to 50 reports, along with oral updates, to the HRC, providing detailed analysis of alleged abuses and violations of international law in Ukraine. These reports have issued recommendations to all duty-bearers and the international community with a view to preventing human rights violations and mitigating emerging risks.

While Ukraine offers a clear case in point, it is far from the only context where potentially preventive measures anchored in rights have been insufficient to prevent deterioration. The 49th session of the HRC also saw the establishment of a group of experts on Nicaragua mandated with investigating human rights violations and abuses committed since 2018. Moreover, the HRC renewed commissions of inquiry in South Sudan, Syria and Belarus, in addition to extending the mandates of Special Rapporteurs and Independent Experts on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Myanmar, Iran, Occupied Palestinian territories and Mali – contexts that have been under scrutiny by the HRC and the General Assembly for years.3 Often used as a house of last resort, the HRC early-warning function remains under-utilised by Member States looking to prevent violations.

Polarisation of the human rights agenda and its impacts on the UN regular budget

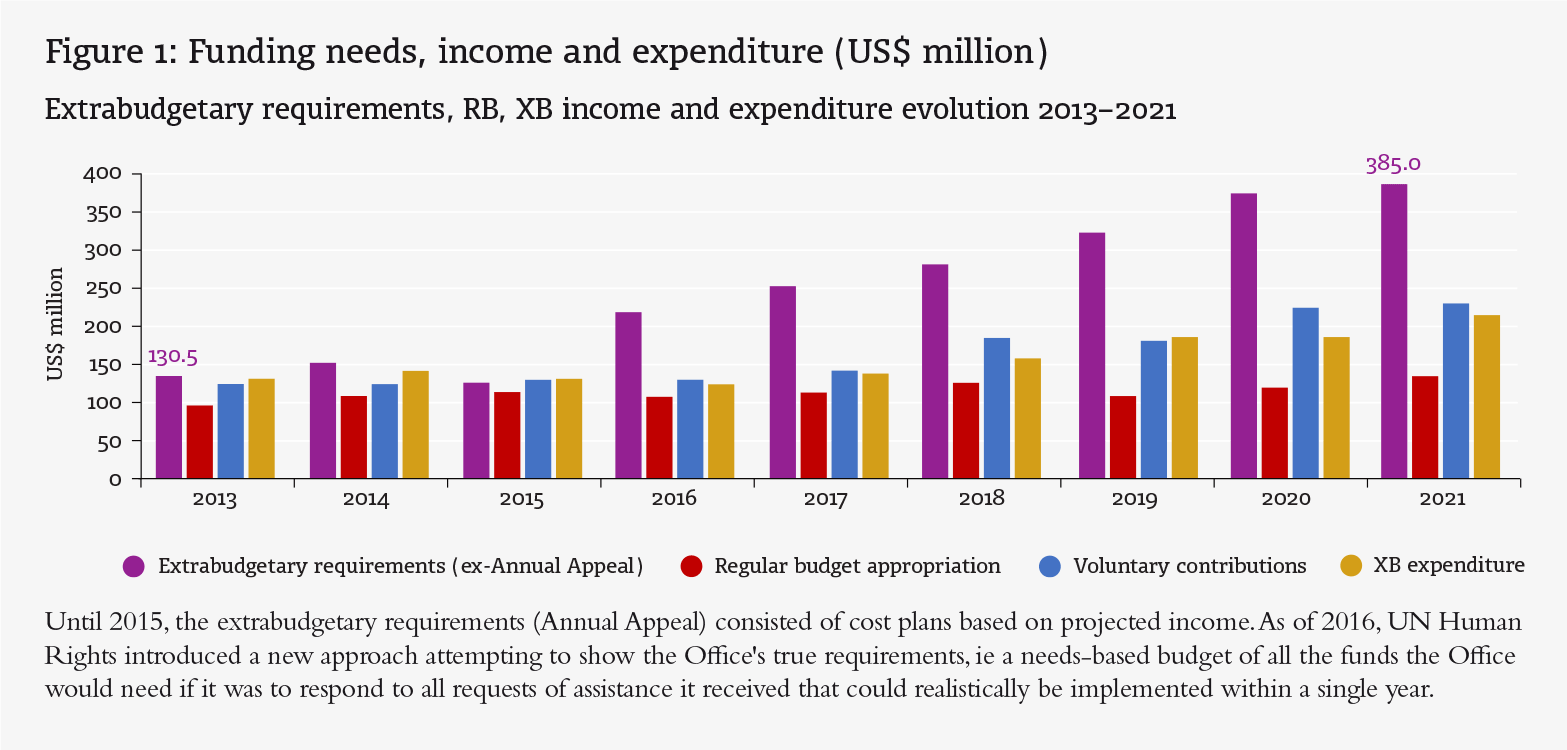

At this time of global crisis, when the UN human rights system is needed most, entrenched polarisation coupled with resource constraints have profoundly impacted implementation of the UN’s normative agenda. The third pillar of the UN remains severely underfunded, with only US$ 136.7 million – or slightly over 4% of the overall UN regular budget (excluding humanitarian affairs) – allocated to human rights in 2022. Cross-regional initiatives to strengthen this pillar since 2012 have not yet translated into a global commitment. Aside from some additional resources allocated in recent years to strengthening treaty bodies and to new mandates established by the HRC, funding for the pillar has seen zero growth.

Despite the level of activity in the HRC testifying to the robustness of the international human rights system, securing regular budget funding for mandated activities has become an uphill battle. The HRC’s 49 session attracted the participation of over 180 dignitaries, with the 35 resolutions adopted requiring an estimated additional funding of over US$ 25 million. Stark divisions, however, have continued to fuel heated discussions at the General Assembly’s Fifth Committee.4 Even so, the HRC continues to issue mandates with a focus on criminal accountability in order to support prosecutorial and judicial processes that require specialised skills and expertise.

The proliferation of mandates has led to the budget allocation process becoming more complex and uncertain, with increasing demands that OHCHR absorb new capacity requirements. In an unprecedented move, Ethiopia tabled a resolution proposing that no funds at all be given to the International Commission of Human Rights Experts on Ethiopia, in contradiction of the intergovernmental HRC resolution establishing it. The move was rejected.

Moreover, arguments that attempt to politicise the human rights agenda (undermining their universality) continue to polarise states’ positions, despite a lack of any defined fault-line that cuts across issues, whether thematic or geographic. Ad hoc alliances formed around resolutions shift even in situations that present similarities. This uncertainty is reflected in voting patterns, in particular for mandates where the voting margin is very narrow.

Implications of an over-reliance on voluntary contributions

In response to this uncertainty and polarisation, and the budget shortfalls that have arisen as a consequence, OHCHR has come to rely increasingly on voluntary contributions, which now fund more than 63% of its activities. The organisation has benefited from an increase in donor funding in recent years, which reached a record high of US$ 227.7 million in 2021.

Increasing reliance on voluntary contributions from a limited number of Member States to fund the UN normative agenda is problematic. Voluntary funding can be unpredictable, creating financial insecurity and reducing both flexibility and sustainability. In 2021, only 24 of the 89 donors provided voluntary contributions of US$ 1 million or above, pointing to an ongoing funding diversification challenge. Earmarking – contained in 63% of the voluntary contributions OHCHR received in 2021 – leads to higher transactional costs, depriving OHCHR of the flexibility it requires to respond to identified human rights priorities and increasing the perception that its work lacks independence.

In addition, rapid movements of funds have followed the abrupt shifts of attention the international community has displayed towards issues of immediate national interest. OHCHR’s ability to adapt to the COVID-19 crisis meant that it received its highest ever levels of contributions in 2020 and 2021: US$ 224.3 and US$ 227.7 million respectively. Subsequently, donor interest shifted to the crisis in Tigray in 2021. OHCHR received more funds than it expected for its immediate work on Tigray and over US$ 10 million in one month for Ukraine.

By contrast, however, OHCHR has failed to obtain the US$ 7.2 million required to maintain its monitoring presence in Yemen, one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises.5 In another concerning development, some of OHCHR’s major donors have indicated the Ukraine crisis will impact their ability to maintain current funding levels for 2022. If this indeed comes to pass, it will have a significant detrimental effect on the UN's ability to fulfil its human rights mandate and for the overall progress in realising the Sustainable Developments Goals (SDGs).

Leveraging partnerships across the UN and beyond

Given the capped regular budget allocation and constrained voluntary contributions, it has become more critical than ever to strengthen cross-pillar synergies and leverage partnerships across the UN system. Human rights is central to the success of the development, peace and security pillars, with the COVID-19 pandemic having shown us the power of aligning development and human rights strategies to reinforce national protection systems. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development sets a clear imperative for the UN to promote people- centred development, with a focus on transformative economies and leaving no one behind.

In this context, the UN Sustainable Development Group has since 2012 supported deployment of Human Rights Advisors (HRAs) as resources for UN Resident Coordinators and Country Teams. In countries where HRAs are deployed (54 in 2021), there is a more systematic integration of human rights into development analysis and planning instruments, including in the Common Country Analyses and the UN Sustainable Development Cooperation Frameworks to achieve the SDGs.

To complement this approach, OHCHR has mobilised, through its Surge Initiative, a team of economic and social rights specialists – including macroeconomists – to reinforce human rights in the design and monitoring of national economic policies.6 This includes long-term investment in public health, education and social protection, in accordance with states’ obligations under international law.

The centrality of protection has also been demonstrated in the context of the UN-led humanitarian coordination architecture and the peace and security pillar. A human rights-based approach to crisis promotes the inclusion and participation of groups left behind. It also reinforces early warning, assists prevention of conflict and its reoccurrence, and aid accountability.

The Call to Action for Human Rights and Our Common Agenda

While robust inter-agency and cross-pillar synergy may not be sufficient to address the structural underfunding of the UN’s normative agenda, it does offer meaningful opportunities to leverage overall UN action. In this regard, the Secretary-General has launched two major initiatives that place human rights activities at the heart of the organisation’s collective action.

In 2020, the Secretary-General issued ‘A Call to Action for Human Rights’, emphasising the responsibility borne by the UN system and its partners for human rights.7 Following this, in his 2021 report Our Common Agenda, he set out a powerful vision for the future of multilateral governance when it comes to tackling global challenges.8 The report begins with a call for a renewed social contract anchored in human rights – an endorsement of their centrality. It is undeniable that the UN human rights system not only helps us understand root causes and precursors to conflict, but provides authoritative guidance on international law and what solutions exist. The Secretary-General’s initiatives have shifted the narrative to understand rights as problem-solving.

The initiatives also call for more stable and sustainable funding to underpin the financial base of the UN human rights pillar.9 An increase in funding allocation commensurate with that seen at the 2005 World Summit, which doubled OHCHR’s regular budget in five years, is critical given the centrality of human rights as per article 1(3) the UN Charter. Moreover, it is needed to help counter the politicisation of human rights activities. The forthcoming 2023 UN Summit of the Future may provide a suitable platform to initiate this conversation.

Footnotes

See Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR),‘Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine’, www.ohchr.org/en/hr-bodies/hrc/iicihr-ukraine/index.

See OHCHR,‘Special procedures of the Human Rights Council’, www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures-human-rights-council.

See United Nations General Assembly,‘Administrative and Budgetary Committee (Fifth Committee) news and updates’, www.un.org/en/ga/ fifth/index.shtml.

Norwegian Refugee Council,‘Yemen: Civilian casualties double since end of human rights monitoring’, 10 February 2022, www.nrc.no/news/2022/february/yemen-civilian-casualties-double- since-end-of-human-rights-monitoring/.

See OHCHR,‘Seeding change for an economy that enhances human rights – The Surge Initiative’, www.ohchr.org/en/sdgs/seeding-change- economy-enhances-human-rights-surge-initiative.

UN Secretary-General,‘The Highest Aspiration:A Call to Action for Human Rights’, 2020, www.un.org/sg/sites/www.un.org.sg/ files/atoms/files/The_Highest_Asperation_A_Call_To_Action_For_ Human_Right_English.pdf.

UN Secretary-General, Our Common Agenda: Report of the Secretary-General (New York: UN Publications, 2021), www.un.org/en/content/common-agenda-report/assets/pdf/ Common_Agenda_Report_English.pdf.