Homi Kharas is a senior fellow at the Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings, where he studies policies and trends influencing developing countries and their prospects for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. Homi Kharas serves on an external advisory committee to the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and previously spent 26 years at the World Bank, latterly as Chief Economist and Director for poverty reduction and economic management in the East Asia region.

Charlotte Rivard is a research analyst with the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution, where she assists with research on development financing and global poverty.

Introduction

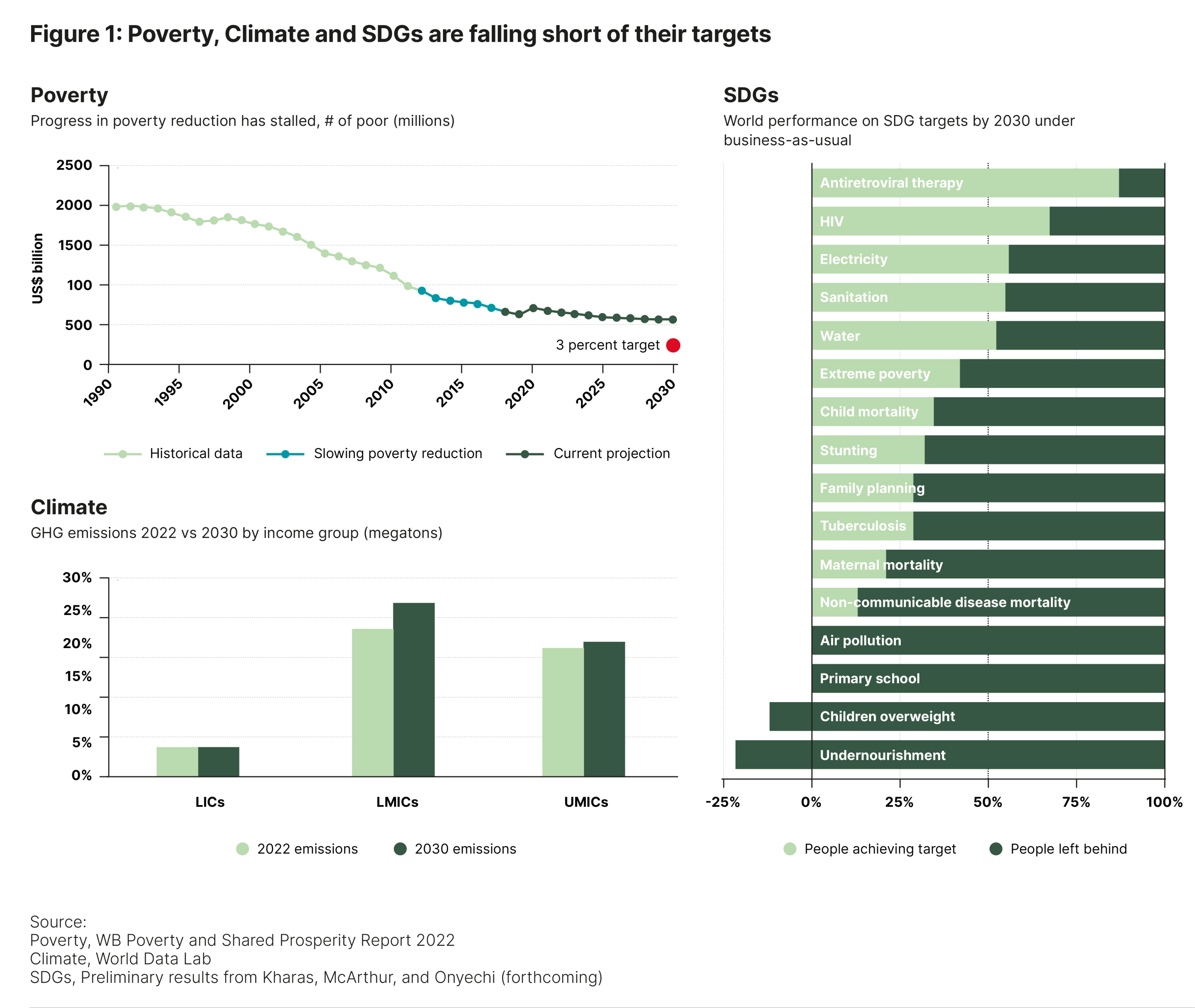

Development financing is stuck amidst a time of immense need. With the COVID-19 pandemic and looming recession, the war in Ukraine and consequent supply chain and food shortages, rising debt distress, and the ever-pressing threat of climate change, developing countries face a multitude of overlapping crises. The global financial system is currently ill-equipped to handle the scale and urgency of needs. In the words of United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres, the system is ‘short term, crisis-prone … and further exacerbates inequalities’.1 While countries attempt to put out the fires in front of them, longer-term targets, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), have been pushed to the back burner. At the midpoint of the 2030 Agenda – eight years since the goals were created – most countries are not on track to meet most of the SDGs, with some indicators even getting worse (Figure 1). Poverty reduction has stalled, meaning that, according to current projections, over 500 million people will be left in extreme poverty in 2030. Greenhouse gas emissions are expected to continue to rise into 2030 across low- and middle-income countries, over the course of a decade when emission reduction is pivotal to keeping climate goals within reach.

The good news is that there is broad recognition that we have a problem. Consensus has grown around the need to rethink the global financial system and adapt to the current landscape, with actors in the multilateral development banks (MDBs), UN agencies and bilateral governments all aligned in calls for transformational change. These reforms should involve a massive scaling up of development financing to tackle imminent and future crises, longer-term SDG targets, and a range of cross-border global challenges – including those related to climate, water, nature and pandemic surveillance – that threaten prosperity everywhere, particularly for people living in poverty.

The big stuck in development financing

Where do development finance flows stand today? Table 1 shows broadly defined net flows over the period 2015–2021 from the four main channels of financing: 1) direct aid from Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development–Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) members;

- multilateral concessional and non-concessional flows;

- flows from non-DAC countries like China and India; and

- private flows.

Development finance is a part of total financial flows to developing countries. The OECD has developed a concept of ‘country programmable aid’ that excludes food aid, humanitarian assistance, aid agency administrative costs, and in-donor refugee costs and student scholarships.2 These flows do not have achievement of the SDGs in developing countries as a prime purpose, and often do not constitute cross-border flows. We exclude these kinds of aid in constructing our figures.

For non-aid flows, we include all flows from institutions with the primary purpose of development finance and all flows to national governments, including their borrowing from bond markets and commercial banks. For private flows, we further include private participation in infrastructure, philanthropy and impact investments. Other private flows, including remittances and other foreign direct investment, are excluded, as these are not ‘programmable’ for long-term development.

Over the period 2015–2021, development finance net flows averaged roughly US$ 500 billion annually, with a typical breakdown of about 60% private flows, 20% multilateral flows, 15% DAC flows and 5% non-DAC flows. Total development financing flows in 2021 (the latest available year) amounted to some US$ 511 billion – a modest US$ 8 billion improvement from the US$ 503 billion estimated for 2020. This was about US$ 100 billion less than in 2017, when developing countries accessed large amounts from bond markets and Chinese banks and development finance flows peaked.

The broad pattern emerging from Table 1 is that development finance flows have been relatively flat since the SDGs were adopted. There is no sign that the hoped for ‘billions to trillions’ is underway. While private participation in infrastructure rebounded from a historic low in 2020, it still remained below pre-pandemic levels in 2021.

Emerging economy donors, like China and India, have cut back, as have the non-concessional lending institutions in DAC countries, perhaps in response to deteriorating creditworthiness in developing countries. Although official development assistance (ODA) has risen, after excluding US$ 30 billion of in-donor refugee costs, the real growth of ODA in 2022 was only 4.6%.3 Even that improvement was not felt by all – Africa saw an 8% decline in aid in real terms as funds were diverted to Ukraine.4 The overall pattern is that development finance is stuck, big-time.

An uncommon agreement on the diagnosis to scale up development finance

The past year has seen an emerging consensus that something must be done to accelerate progress on the SDGs and address global challenges related to climate change, pandemic surveillance, nature, water and conflict. There are growing calls from several sources to scale development financing to a level commensurate with these challenges. The UN Secretary-General has called for an additional US$ 500 billion in development financing in his SDG Stimulus Plan. In combination with current levels, this would total roughly US$ 1 trillion per year.5

Others estimate even greater needs: according to a report by the High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance, co-chaired by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the London School of Economics, an additional US$ 1.3 trillion dollars annually is needed by 2025, relative to 2019 spending levels, to support climate mitigation and adaptation, human capital, and land use.6 This figure is drawn from the Songwe, Stern and Bhattacharya report for COP27,7 based on academic studies.8 The Bridgetown Initiative calls for MDBs to invest US$ 1 trillion in climate resilience.9

The World Bank concludes that by 2030 incremental finan-cing for low-carbon pathways should average 1.4% of developing country gross domestic product (GDP) – as high as 8% in low-income countries and progressively lower in middle-income countries. This translates into an incremental US$ 560 billion in financing (excluding China).10 These estimates, however, only include the incremental costs of a transition to a low-carbon economy, without additional support for SDGs. The World Bank cautions that it is impossible to fully separate climate needs from development needs, as climate vulnerability is closely linked to large infrastructure gaps. Hence, closing the infrastructure gap can be considered both a development activity and a cost of pursuing adaptation and resilience to climate change.

Separately, the World Bank estimates in its Evolution Roadmap that US$ 2.4 trillion is needed in annual average spending to address the global challenges of climate action, conflict and pandemics between 2023–2030.11

The IMF estimates, based on a small sample of four countries, the incremental public and private spending to achieve the SDGs could amount to 14% of GDP.12 The setbacks associated with COVID-19 alone could cost about 2.5% of GDP. The OECD estimates the SDG domestic and external financing gap in developing countries at US$ 2.5 trillion in 2019, growing to US$ 3.9 trillion in 2020, mostly as a result of revenue losses and COVID-19-related spending.13

Simply put, every report from a major international development agency agrees that a sharp scale-up in development finance is needed. Such agreement is rare and provides grounds for optimism that something will be done.

The plan

There are three elements of a new development finance plan taking shape. First, unleash MDBs to play a far greater development finance role, taking advantage of their financial leverage and risk-sharing characteristics. Thus, MDBs are being called upon to expand their mandates to include global challenges, to be accompanied by an expansion in their financing. Second, address debt challenges, at least for a small number of countries currently under significant stress. Third, provide liquidity to overcome humps in the repayment of Eurobonds and other private loans.

Unleash the multilateral development banks

In 2020 and 2021, MDBs stepped up their development finance. The World Bank implemented ‘surge financing’, committing an additional US$ 150 billion in 2020 and US$ 170 billion in 2021 (although a far smaller amount was actually disbursed).14 The surge has, however, depleted the capacity of both the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Development Association (IDA) to sustain their financing.

For example, without additional contributions, IDA financing for financial year (FY) 24 and FY25 could decline by US$ 10 billion (30%) compared to FY23 levels (the so-called ‘IDA cliff’).15 Similarly, to avoid an IBRD cliff, shareholders agreed to a package of reforms that will permit IBRD to lend an additional US$ 50 billion over the next ten years.16

These measures are a first step in a deeper conversation about the World Bank’s mission, vision and operating model, instigated by Secretary of the Treasury, Janet Yellen, who, in November 2022, called for the World Bank to produce an ‘evolution roadmap’.17 The initial report delivered by the Development Committee proposed a new mission statement: ‘To end extreme poverty and boost shared prosperity by fostering sustainable, resilient, and inclusive development’.18

Spearheading these reform efforts will be a new World Bank president, Ajay Banga, former chief executive officer of Mastercard. Banga has indicated that he will be supportive of sustainable development efforts. At Mastercard, he founded the Center for Inclusive Growth in 2014, which provides research and philanthropy for inclusive growth. Coming from the private sector, he is well positioned to use the World Bank to mobilise private finance for development and form partnerships across a wide range of financial institutions.19

Address debt overhangs

Private finance has become increasingly inaccessible to developing countries and more costly as market interest rates rise to combat inflation. In a sample of 50 developing country central banks, 43 increased interest rates in 2022.20

Sovereign credit ratings for developing countries have been consistently downgraded. Between April 2022 and April 2023, 17 developing countries had their ratings downgraded at least once by a major credit rating agency, and an additional 16 have had their outlooks downgraded (Figure 2).21 Only nine countries received modest upgrades. Compared to pre-pandemic ratings, 49 countries have been downgraded, including several defaults.

Faced with these risks, foreign direct investment in SDG sectors has fallen sharply.22 The value of greenfield investment projects for SDG sectors fell by over 30% in 2020, only recovering by a modest 5% in 2021. Private participation in infrastructure remains well below its pre-pandemic levels, standing at US$ 71 billion in 2021.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI), which came to close at the end of 2021, reprofiled $12.9 billion in debt service, but these amounts must now be gradually repaid.23 According to the IMF, about 15% of low-income countries are in debt distress and 45% are debt vulnerable.24

The Common Framework was supposed to quickly resolve debt overhang situations but has proven to be slow and cumbersome in practice. Recently, a few positive process steps have been taken. While greater transparency in debt and of debt sustainability analysis, protection of MDBs’ preferred creditor status, and the need for multilateral, rather than bilateral, negotiations are useful clarifications, real results are still limited. China has an important role in these debt restructuring conversations given that it held US$ 114 billion in outstanding loans to developing countries in 2021.25

Roundtable conversations on debt restructuring continue to discuss issues such as comparable treatment, cut-off dates, treatment of domestic and short-term debt, treatment of collateral and value recapture, and state contingent clauses in debt contracts.

Liquidity

Many developing countries are vulnerable to external shocks and face uncertainties in accessing new capital to roll-over existing debt. The world created a large pool of new liquidity in the form of a new issuance of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) worth US$ 456 billion to deal with the pandemic shock, but only 4% of this was provided to IDA-eligible low- and lower middle-income countries.

Rich countries have pledged to voluntarily reallocate their excess SDR holdings to help low-income countries, for example the G7 pledged to reallocate US$ 100 billion to the Resilience and Sustainability Trust. These pledges have not yet been fully met, however, and other concessional windows, such as the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust and the Catastrophe Containment and Relief Trust, remain inadequately financed.

A liquidity issue looms in the need to roll-over large repayments falling in 2024 and following years due on Eurobonds and other private debt. Figure 3 shows these repayments have climbed significantly since 2015, when low and lower middle-income countries first approached bond markets. The large scale and speed of accessing finance from the bond markets – which had presented such an opportunity to developing countries – has now become a burden when it comes to repaying these large sums.

Repayments will reach historically high levels in 2024, before falling to more comfortable levels in 2027. Figure 3 also shows that most debt service will be owed to private bondholders and banks in the coming years. Bilateral creditors, who control the debt restructuring process, only hold about a seventh of total debt service due in 2023. This is why official agreements in the G20, such as the DSSI, have been so limited in scope and impact on low-income countries.

Conclusion

Although international development finance is seemingly stuck, the elements of a plan to unstick it are appearing. The plan is based around three parallel tracks: 1) an effort to unleash new finance for long-term investments and growth through the MDBs; 2) talks to establish a common understanding of how debt restructurings should be pursued; and 3) converting pledges for more liquidity, including SDR reallocations, into reality.

Endnotes

United Nations, ‘Guterres calls for G20 to agree $500 billion annual stimulus for sustainable development’, UN News, 17 February 2023, https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/02/1133637.

Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), ‘Country programmable aid (CPA)’, www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sus-tainable-development/development-fi-nanc….

OECD, ‘Foreign aid surges due to spending on refugees and aid for Ukraine’, 12 April 2023, www.oecd.org/newsroom/foreign-aid-surges-due-to-spending-on-refugees-an….

OECD, ‘April 2023 – preliminary figures’, https://public.flourish.studio/story/1882344/.

Vera Songwe, Nicholas Stern and Amar Bhattacharya, ‘Finance for Climate Action: Scaling Up Investment for Climate and Develop-ment: Report of the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance’, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), November 2022, www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/IHLEG-Financ….

Amar Bhattacharya et al., ‘Financing a Big Investment Push in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies for Sustain-able, Resilient and Inclusive Recovery and Growth’, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, LSE and Brookings Institution, May 2022, www. lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Financing-the-big-invest-ment-push-in-emerging-markets-and-de-veloping-economies-for-sustainable-resil-ient-and-inclusive-recovery-and-growth-1.pdf.

Chloé Farand, ‘Mia Mottley builds global coalition to make financial system fit for climate action’, Climate Change News, 23 September 2022, www.climatechangenews. com/2022/09/23/mia-mottley-builds-global-coalition-to-make-financial-system-fit-for-cli-mate-action/.

World Bank Group, ‘Climate and Development: An Agenda for Action – Emerging Insights from World Bank Group 2021–22 Country Climate and Development Reports’, 2022, https://open-knowledge.worldbank.org/entities/publication/fccbefad-b48d….

World Bank, Development Committee, ‘Evolution of the World Bank Group – A Report to Governors’, 30 March 2023, www.devcom-mittee.org/sites/dc/files/download/Docu-ments/2023-03/Final_….

Dora Benedek et al., ‘A Post-Pandemic Assessment of the Sustainable Development Goals’, IMF Staff Discussion Note 2021/003, International Monetary Fund (IMF), 27 April 2021, www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Dis-cussion-Notes/Issues/2021/04/27/A….

World Bank, ‘World Bank Group Ramps Up Financing to Help Countries Amid Multiple Crises’, press release, 19 April 2022, www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-re-lease/2022/04/19/-world-bank-group-r….

Shabtai Gold, ‘David Malpass: World Bank can lend “up to” $50B more over next decade’, Devex, 30 March 2023, www.devex.com/news/david-malpass-world-bank-can-lend-up-to-50b-more-ove….

Homi Kharas, ‘Ajay Banga: The US nominee for World Bank president’, Brookings Institute, 24 February, 2023, www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2023/02/24/ajay-banga-the-us-….

Ingo Pitterle et al. ‘World Economic Situation and Prospects: April 2023 Briefing, No. 171’, Global Economic Monitoring Branch of the Economic Analysis and Policy Division of UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 3 April 2023, www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/world-economic-sit-uation-….

Trading Economics, ‘Credit ratings by country’, https://tradingeconomics.com/country-list/ rating (accessed 4 April 2023).

UN Conference on Trade and Development, ‘Global Investment Trend Monitor, No. 40’, January 2022, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diaeiainf2021d3_en.pdf.

World Bank, ‘Debt Service Suspension Initiative’, 10 March 2022, www.worldbank.org/en/topic/debt/brief/covid-19-debt-service-sus-pension….

Kristalina Georgieva, ‘The time is now: We must step up support for the poorest countries’, IMF Blog, 31 March, www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Arti-cles/2023/03/31/the-time-is-now-we-must-step-….