Pedro Conceição is Director of the Human Development Report Office at the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and lead author of the ‘Human Development Report’ since 2019. Previous positions held include Director, Strategic Policy, at the Bureau for Policy and Programme Support; Chief Economist and Head of the Strategic Advisory Unit at the Regional Bureau for Africa; and Deputy Director and Director of the Office of Development Studies. He has written extensively on financing for development, global public goods, inequality, and the economics of innovation and technological change as well as development. Prior to joining UNDP, Pedro Conceição was an Assistant Professor at the Instituto Superior Técnico, Technical University of Lisbon, Portugal, teaching and researching science, technology and innovation policy. He has degrees in Physics from Instituto Superior Técnico and in Economics from the Technical University of Lisbon and holds a doctoral degree Public Policy from the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin in the United States.

Introduction

The imperative of providing global public goods is sometimes perceived as competing with other priorities associated with development, such as eliminating poverty and promoting the convergence of living standards of low- and middle-income countries with those with higher levels of income. This contribution shows how failure to provide global public goods actually exacerbates development challenges, be it increases in extreme poverty or divergence in living standards. Evidence comes from the impact on human development from the way in which the COVID-19 pandemic was managed.

Looking ahead, the contribution shows how the provision of global public goods, like climate change mitigation, is key to advance inclusive and sustainable human development. Moreover, domestic support in high income countries for the international transfer of resources to lower income countries is associated both with altruistic motivations of supporting the poor in lower income countries, as well as with addressing globally shared challenges. In sum, financing global public goods is a complement, not a substitute, for either humanitarian assistance or official development assistance. Moreover, failure to advance an agenda focused on providing global public goods can exacerbate challenges to multilateralism, which may be perceived as not delivering on contemporary and emerging challenges.

The world today is vastly different from what it was in the aftermath of World War II, when the idea and practice of international development emerged. A core tenet of today’s world is the reality of living on a shared planet undergoing dangerous changes for human and other forms of life, as well as societies that are deeply connected via instantaneous flows of information powered by rapidly accelerating technological transformations, such as artificial intelligence. A multilateralism fit for the 21st century has to take account of this new reality, and a global public goods lens provides a structured way of understanding these challenges as well as what to do to address them.

By many accounts, the world seems to be rebounding from the globally traumatic experience of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, the latest Human Development Report for 2023 and 2024 documents that the global Human Development Index (HDI) is projected to have reached the highest value on record in 2023 – as a whole and on each of its three dimensions, associated with standards of living, and achievements in health and education.2 These three dimensions were heavily affected by the pandemic, which was simultaneously an economic, health, and education crisis that hit all the world’s countries simultaneously. But there are two concerning characteristics of this rebound.

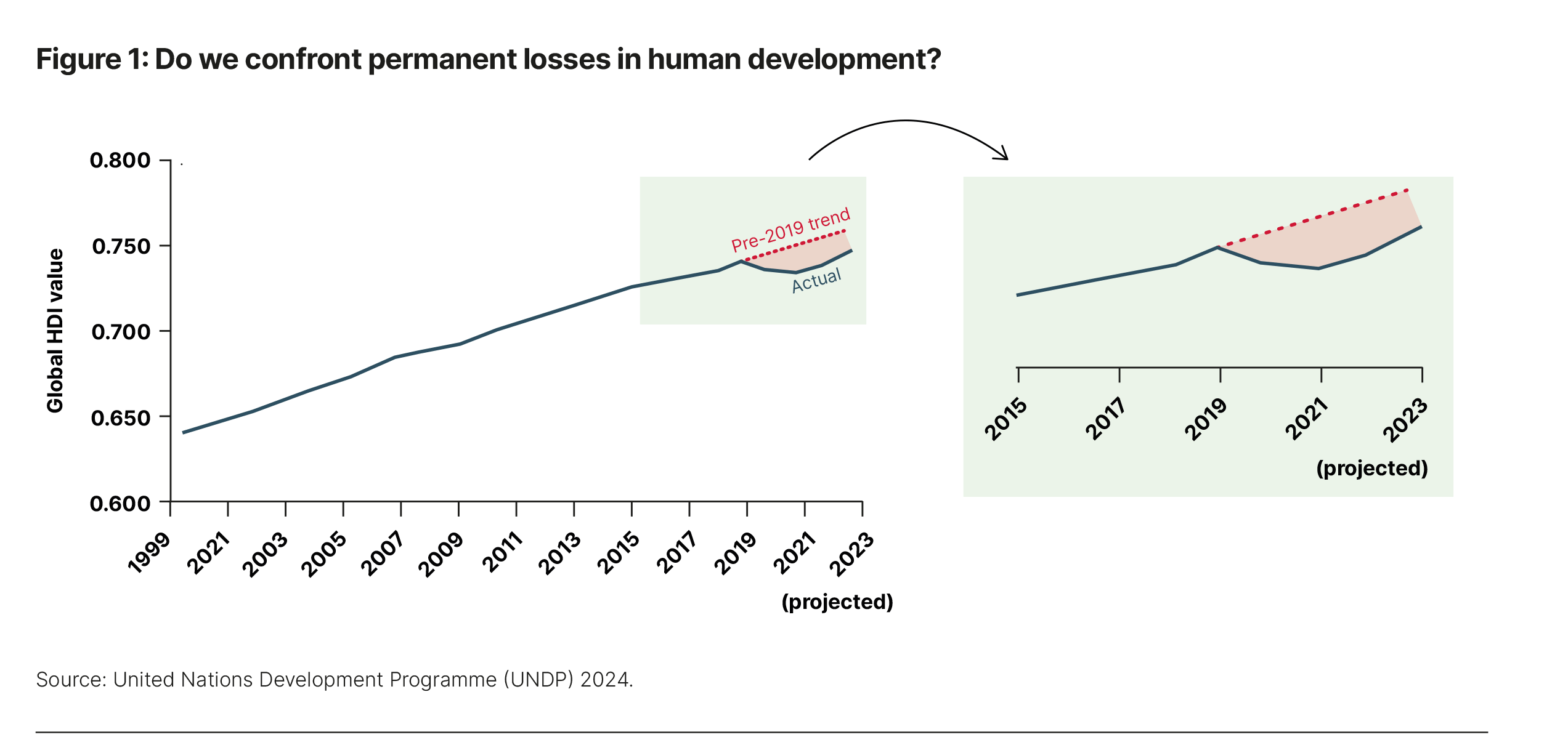

First, given the decline of the global HDI in 2020 and 2021, the recovery that started in 2022 is on a path that sits below the pre-2019 trend (figure 1). If the progress remains below the pre-2019 trend for a long time, this represents long-lasting losses in human potential, compared with what we would have expected had the decline in the global HDI never taken place. If the actual path of progress never bends to move it above the pre-2019 trend, the scarring from the temporary dip in human development would become permanent. The recognition that temporary shocks can have long-lasting, potentially permanent scarring effects, is increasingly recognised by a series of new studies published in recent years.3 The fact that shocks, even when transitory, can have long-term or even permanent effects, changes the calculus about how much one should invest in preventing them or, at a minimum, allocate resources to mitigate their negative impacts on people.4 These investments will have to be much higher than under the assumption that shocks are transitory and the recovery implies that things will go back to the pre-shock path.

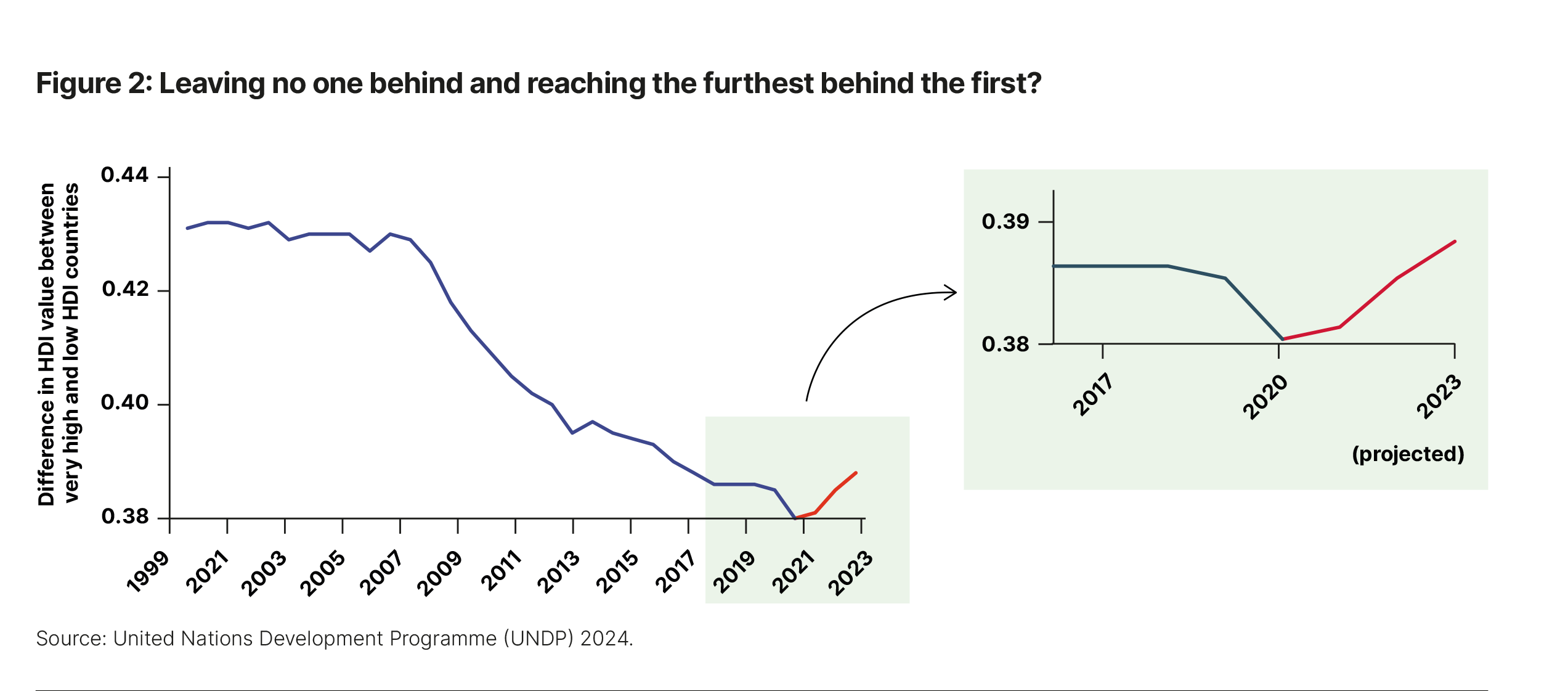

Second, after decades in which the countries at the bottom of the HDI rank have narrowed their distance from the countries at the top – the very essence of the notion of ‘development’ – those gaps are now increasing, with a reversal from a process of convergence to one of divergence that has unfolded over the last four years (figure 2). This goes against the pledge of the 2030 Agenda of leaving no one behind and reaching the furthest behind first: the opposite is happening.

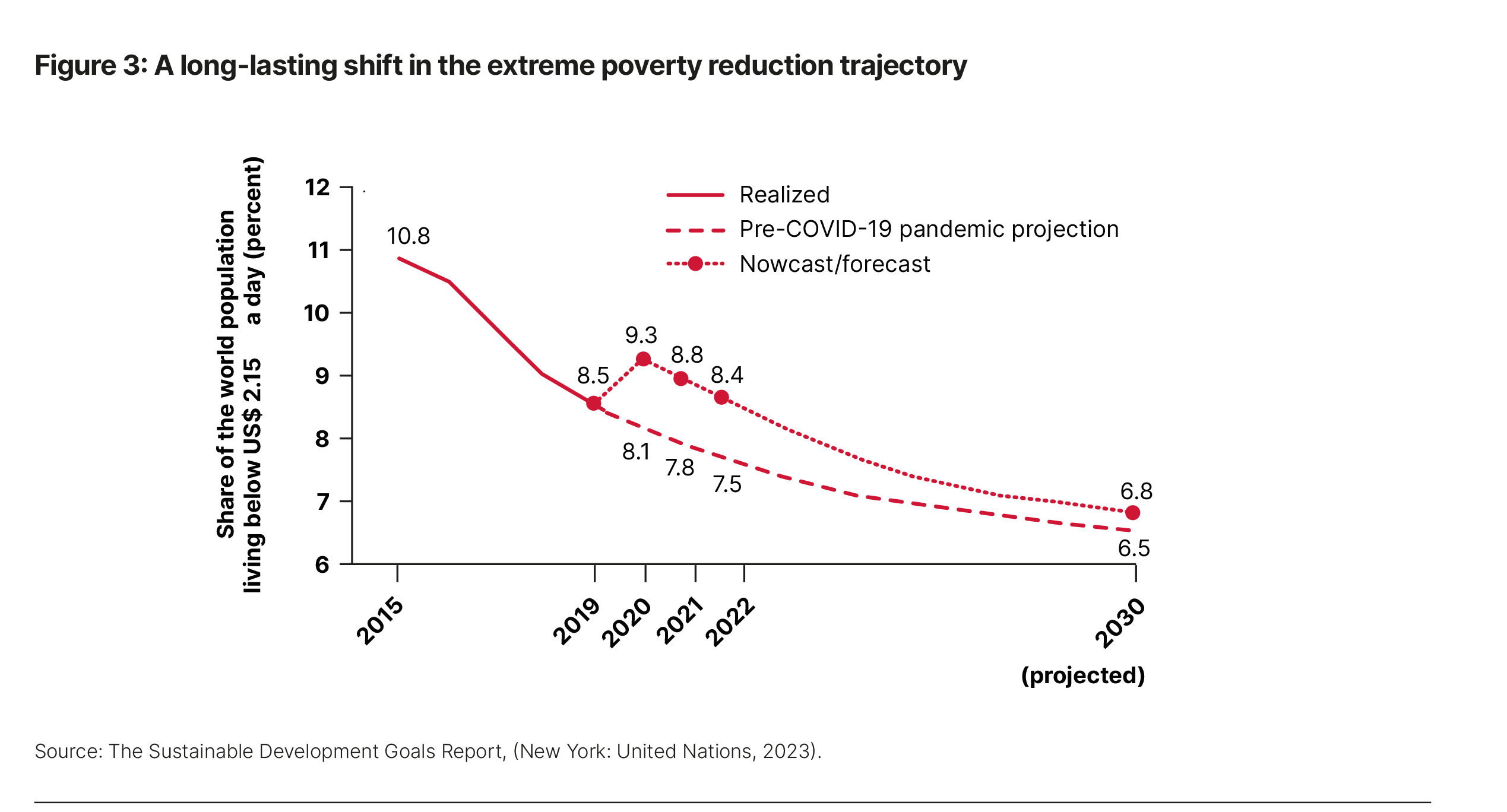

The two concerning characteristics revealed by the analysis of the HDI are also reflected in the trajectory of reduction in extreme poverty. The path has shifted, potentially permanently, to a slower trajectory than would have been expected had the COVID-19 shock not taken place or measures adopted to avoid the increase in extreme poverty, and the rank of the extreme poor increased, with the headcount poverty ratio increasing by almost one percentage point from 2019 to 2020 (figure 3). So, the message is clear, the mismanagement of the COVID-19 pandemic hurt the poor, hurt development, and the implications will be long-lasting, potentially permanent. But, oh well, tant pis, we could have done better, but it is what it is. Let us now redouble the efforts to eradicate poverty and get low-income countries to converge, once again, to the standards of living of the high-income countries. While this is absolutely needed, it would be a missed opportunity not to reflect more deeply about what transpired during the COVID-19 pandemic.

We can look at it from multiple perspectives, with mistakes made at different points, by different actors, at multiple scales. But, fundamentally, the response to COVID-19 reflects the mismanagement of a challenge in which countries were interdependent with one another. Even a country with all the resources in the world, with all the right policies within borders, would be subject to decisions made elsewhere. How else can we explain that over 90% of the world’s countries suffered a decline in their HDI during the 2020 and 2021 period?5

From this point of view, the mismanagement of COVID-19 represents just one case of several others in which the fate of countries is interlinked. Of course, low-income countries, and, within countries, the poorest and most vulnerable, need to be supported and assisted. But what the COVID-19 experience is telling us is that if the international community does not systematically address those challenges in which countries are interlinked and mutually dependent on one another, poverty will increase, development will regress, people will suffer, particularly those with the least means to respond to the consequences of that mismanagement.

One way of looking at this type of interdependent challenges is through the prism that they reflect the under provision of global public goods.6 The adequate management of these interdependent challenges requires enhancing the provision of global public goods within, in turn, depends on collective action across many actors, including (and often primarily) by countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic is in our rear-view mirror now, but we know that there will be more pandemics in the future. While we cannot predict when the next pandemic will happen, pandemic control is but one example of global public goods, and we do know about the implications of not providing other global public goods looking into the future. For example, take a glimpse at what is in store for a world that fails to enhance the provision of the global public good of climate change mitigation.

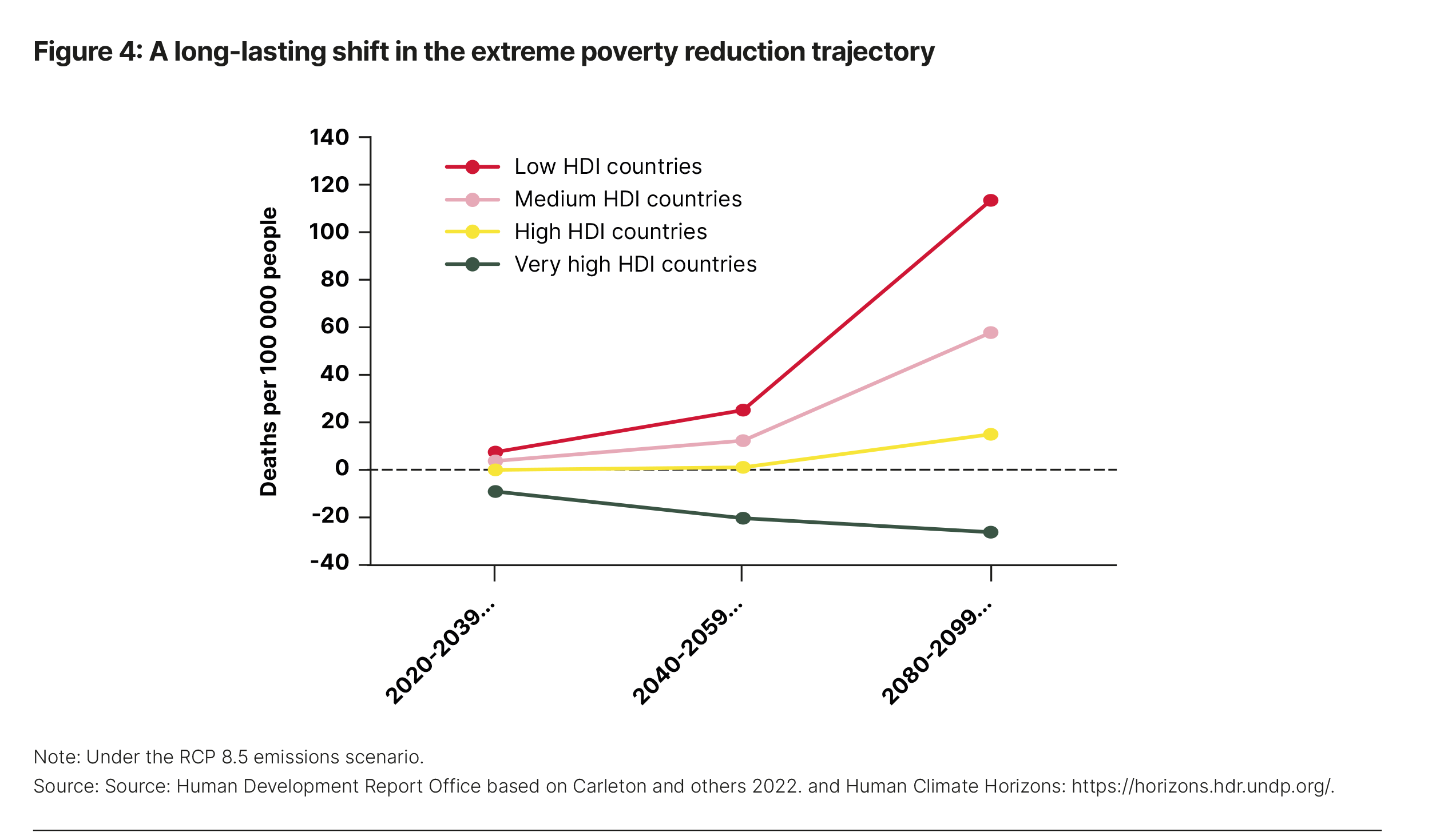

Climate change models provide increasing precision about the kind of hazards the world will confront. One such hazard is change in temperature, that will vary across space and will have differentiated impacts on different aspects of human development not only across, but also within countries. For example, under a scenario of high emissions of greenhouse gases, inequalities in mortality rights will explode from now until the end of the century, with the incidence of increases falling more heavily on countries the lowest their levels of human development (figure 4).

The provision of global public goods requires varying levels of cooperative action among states and wide-ranging actors that can contribute in different ways. Cooperation across countries needs to go beyond cooperation within countries, which is supported by affiliation with abstract notions, such as being part of a nation.7 National parochialism – strong cooperation within countries – is ubiquitous.8 But global public goods require some form of transnational cooperation that transcends country boundaries.9

Much of the discussion around the conditions for trans-national cooperation take the country as the unit of analysis. But it is also important to look within countries: what are the domestic factors that may hinder transnational cooperation?

Turning the lens inward: How political polarisation within countries harms the provision of global public goods

One of the barriers to international cooperation is associated with within-country political polarisation, which is particularly harmful when it takes the form of affective polarisation, as people favour their group even more and other groups even less. Political polarisation goes beyond differences in views between various social groups. It collapses people’s beliefs and preferences into differences defined by a single, salient group identity, coupled with animosity towards those with different viewpoints and priorities.

Polarisation is often associated with people perceiving their differences as zero-sum, making them less likely to seek joint actions and identify shared goals. Zero-sum beliefs make people in polarised societies less likely to trust or associate with individuals from an opposing political or ideological camp10 and more likely to seek social and moral distance from their perceived outgroups and describe their political opponents in dehumanizing or derogatory terms.11 Zero-sum beliefs lead to predictable psychological reactions and behaviours driven by the idea that if one country gets ahead, others must be left behind, and vice-versa.12 Narratives premised on zero-sum beliefs tend to make countries less inclined to cooperate with others13 and are at the root of political polarisation in countries.14

Polarisation shaped by zero-sum beliefs can also alter the functioning of political institutions, leading to gridlock and dysfunction. And because it is often deployed as a political strategy, it can create conditions for a vicious cycle: polarising rhetoric and mobilisation by one party leads opposing groups to also adopt polarising messages.15 Thus, polarisation coupled with zero-sum beliefs has contributed to recent threats to democratic norms and practices,16 sometimes increasing support for authoritarianism.17

The rise in political polarisation and zero-sum beliefs makes international cooperation more politicised and contested in domestic politics, enflaming beliefs and narratives about international institutions. Partisanship and group affiliation often determine people’s preferences on whether leaders should engage in international cooperation and how.18 Thus, polarisation can also contribute to policy instability, where shifts in political power are accompanied by dramatic policy changes, including on matters of international cooperation and engagement, with direct bearing on the prospects for the provision of global public goods.

Political polarisation’s impact on international cooperation is manifested, in part, through reduced support for official development assistance in more polarised high-income countries (see also the contribution of John Hendra in this volume).19 It is also manifested in reduced domestic support for global public goods, such as mitigating climate change.20 Scepticism about international cooperation is not new.21 But there is a growing recognition that lack of domestic support for international cooperation has parallelled the increase in political polarisation.22

International cooperation has become more politically contentious in countries where political polarisation around economic inequality and immigration has gained prominence in public debate.23 The package of openness that international institutions are associated with – the combination of economic integration with exposure to foreign cultural influences and ideas – can contribute to perceptions of insecurity and become a fault line in political polarisation.24 Cultural explanations also feature popular support for leaders espousing nationalism, protectionist policies and opposition to outside influences, complementing economic explanations for backlash against international engagement.25

With rising polarisation, international cooperation can be undermined by political campaigns against international institutions. Participation in international institutions can become polarising. Polarisation can make the domestic political dynamics of international participation (domestic ratification processes) uncertain and disincentivise the executive branch of governments from entering agreements. Other nations may view a polarised country as less reliable and predictable in its foreign policy decisions, reducing trust in its commitments and alliances. One country’s effort to contest them can prompt others to do the same, contributing to a contagion effect.26 And the failure of such efforts can intensify contestation on the basis that the international institution in question has proven unwilling to accommodate demands.27 Given the current state of global politics and the polarisation examples listed, international collective action can be enhanced in part by expanding international financing for international cooperation beyond official development assistance to include financing for domestic contributions to global public goods, as argued in the next section.28

Enhancing international collective action – now

The prospects for cooperation might seem uncertain given increases in domestic political polarisation just described. In addition, geopolitical upheaval is reshaping the conditions for international collective action. Even though the current geopolitical upheaval may hinder international institutions, there is no reason to give up on the aspiration of enhancing collective action because of geopolitical challenges –and there is perhaps even more reason to pursue collective action, including through multilateral organisations.

Continuing with the theme of looking inward, the extent of domestic support to channel resources internationally is crucial for prospects for international cooperation. A key question in this regard is whether arguments to finance global public goods crowd out the motive to provide official development assistance.29 There are reasons to believe that crowding out domestic motivations is unlikely.

Domestic support for international flows of resources can be primarily motivated by a commitment by people living in high income countries to support the development aspirations of lower- and middle-income countries, as in official development assistance. Financing for global public goods follows a different rationale – international flows are meant to enhance the receiving countries’ ability to contribute to the provision of global public goods.30 Still, even if the concern is purely motivated, say, by pledge of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to leave no one behind, the provision of global public goods still matters, given that their under provision can drive exclusion and inequality, as argued earlier in this chapter. Moreover, when the incidence of benefits from the provision of global public goods is favourable to those who have the least, that provision can be progressive.31

Using public resources internationally depends on support from domestic constituencies. A rationale to finance global public goods might be seen to risk alienating domestic constituencies that support international flows and development cooperation motivated by altruistic, and even moral, reasons. Those reasons sustain support for humanitarian aid to save lives and income transfers to low-income countries and people living in fragile settings. To address this concern, it is important to establish, first, whether people who support distribution at the national level also support it internationally.

While individual support for international flows of resources is a new area of study, the main determinants of that support, whatever the rationale for the flows, seem to be people’s beliefs about the geographic and moral boundaries of concern.32

Do people believe they hold moral obligations towards others anywhere in the world, a more universalist belief, or only to those who are closer or similar, including those living in the same country (a more parochial belief)? The variation in these beliefs is widespread both within and across countries, but it is possible to place individuals along a spectrum from lower to higher levels of universal beliefs.

Evidence from 60 countries with 85% of the world’s population and 90% of global GDP reveals a strong correlation between more universal beliefs and support for the global poor versus helping the local poor and for protecting the global environment versus protecting the local environment.33

So, people who hold more parochial beliefs are not opposed to redistribution as such, since they support it when asked about local or community-based redistribution.34 Thus, there is little reason to believe that presenting a rationale for international flows from high-income countries to finance global public goods would dilute a commitment to international flows based on altruistic motives for domestic support for international transfers, given that the underlying motive for domestic public support for international flows is associated with less parochial beliefs. Even if altruism were the only motive for domestic support, enhancing the provision of many global public goods is key to reducing global inequalities as well as vulnerability to poverty and other deprivations. In addition, some evidence suggests that people in low- and middle-income countries do not always favour international aid as a means of reducing intercountry inequality,35 with recipients more interested in framings that address justice and enhance dignity and agency36 than in charity-based rationales that recipients may perceive as stigmatising.37

Conclusion

In sum. Advancing arguments for financing global public goods does not imply less support for international flows from high-income countries. Financing global public goods is likely to result in the need to substantially increase international flows and potential domestic resource mobilisation in high income countries. But it is likely to enhance global equity through two channels. One, by mitigating the drivers of inequality associated with the under provision of global public goods. And two, by generating ancillary national benefits, such as less local pollution or poverty through job creation which is typically one of the explicit intents of official development assistance.

Multilateral institutions might need to articulate more clearly their potential role in channelling these resources, building, but also expanding, on their track record of pooling and allocating international financial resources to meet country needs.38 This is well established in the humanitarian realm, for instance, with strong evidence suggesting that when the United Nations allocates humanitarian assistance, it does so on the basis of actual needs and is not driven by other considerations. The expansion would need to consider supporting low- and middle-income countries to contribute to global public goods.

Endnotes

United Nations Development Programme, ‘Human Development Report 2023/2024, Breaking the gridlock’ (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2024), https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2….

See, for instance, Diego Anzoategui, Mark Gertler, Diego Comin and Joseba Martinez,

‘Endogenous Technology Adoption and R&D as Sources of Business Cycle Persistence’, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 11(3), 2019, pp 67-110; Hannes Schwandt, and Till M. Von Wachter, ‘Socioeconomic Decline and Death: Midlife Impacts of Graduating in a Recession’, Working Paper 26638 (Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020); Laurence M. Ball, ‘Long-Term Damage from the Great Recession in OECD Countries’, European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies 11(2), 2014, pp149-160.

For more details on this perspective and a definition of global public goods see United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) 2024. For seminal work on global public goods see Inge Kaul, Isabelle Grunberg and Marc Stern, ‘Global Public Goods: International Cooperation in the 21st Century’, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999); Inge Kaul, Pedro Conceição, P., Katell Le Goulven, and Rondald U. Mendoza, ‘Providing Global Public Goods: Managing Globalization’ (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003); Inge Kaul and Pedro Conceição, ‘The New Public Finance: Responding to Global Challenges’, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006a); Kaul, and Pedro Conceição, (eds.), ‘Why Revisit Public Finance Today’ The New Public Finance: Responding to Global Challenges. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006b).

Kwame Anthony Appiah, ‘The Importance of Elsewhere’, Foreign Affairs 98(2), 2019, pp 20-26; The same applies to the cultural similarity of people that affiliate with the same religion, even when they live in different countries, Cindel. J. M White, Michael Muthukrishna, Ara Norenzayan, 2021. ‘Cultural Similarity among Coreligionists within and between Countries’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2021, pp 18(37): e2109650118.

For the analysis of the difference in cooperation within and across countries see Hillie Aaldering and Robert Böhm, ‘Parochial Versus Universal Cooperation: Introducing a Novel Economic Game of within- and between-Group Interaction’, Social Psychological and Personality Science 11(1), 2020, pp 36-45.

Lily Chernyak-Hai and Shai Davidai, S. 2022 ‘Do not teach them how to fish: The effect of zero-sum beliefs on help giving’, Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 151(10), 2022, pp 2466–2480, https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0001196.

Shai Davidai and Martino Ongis ‘The Politics of Zero-Sum Thinking: The Relationship between Political Ideology and the Belief That Life Is a Zero-Sum Game’. Science Advances 5(12), 2019, pp 2029, https://www.science. org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.aay3761; Sahil Chinoy, Nathan Nunn, Sandra Sequeira and Stefanie Stantcheva, ‘Zero-Sum Thinking and the Roots of Us Political Divides’, 2023, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/stantcheva/files/zero_sum_political_d….

See Danny Osborne, Thomas H. Costello, John Duckitt and Chris G. Sibley, ‘The Psychological Causes and Societal Consequences of Authoritarianism’, Nature Reviews Psychology 2(4), 2023, pp 220-232 for the psychological causes of authoritarianism, compounded by worldviews associated with perceptions of threat. Worldviews that see the world as competitive also yield more violations of democratic norms and practices that do not necessarily take the form of authoritarianism.

Matthias Ecker-Ehrhardt, ‘Why Parties Politicise International Institutions: On Globalisation Backlash and Authority Contestation’, Review of International Political Economy 21(6), 2014, pp 1275-1312; Catherine E. De Vries, Sara B Hobolt and Stefanie Walter, ‘Politicizing International Cooperation: The Mass Public, Political Entrepreneurs, and Political Opportunity Structures’, International Organization 75(2), 2021, pp 306-332.

See Christina J. Schneider, ‘The Domestic Politics of International Cooperation’. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018), https://doi. org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.615; Tobias Heinrich, Yoshiharu Kobayashi and Edward Lawson Jr, ‘Populism and Foreign Aid’, European Journal of International Relations 27(4), 2021 pp. 1042–1066.

For instance, Ian Hurd, ‘The Case against International Cooperation’, International Theory 14(2), 2022, pp 263-284 argues for recognising that cooperation cannot be considered unequivocally beneficial; rather, it generates benefits to some groups over others, and the political responses to this must be understood.

Catherine E De Vries, Sara Hobolt, and Stefanie Walter, (2021) ‘Politicizing International Cooperation: The Mass Public, Political Entrepreneurs, and Political Opportunity Structures’, International Organization 75(2), 2021, 306-332; Michael Zürn, Martin Binder and Matthias Ecker-Ehrhardt Zürn, 2012. ‘International Authority and Its Politicization’, International Theory 4(1), 2012, pp 69-106; See note 18 Ecker- Ehrhardt 2014.

For instance, the international concessional financing of the incremental cost of an investment that contributes to a global public good, compared to the size of the investment that a country would undertake considering only the country benefit alone, which is an approach taken by the Global Environmental Facility (see King 2006.)

Kenneth King, ‘Compensating Countries for the Provision of Global Public Services’ in Inge Kaul and Pedro Conceiçāo, (eds), ‘The New Public Finance: Responding to Global Challenges’, (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2006). pp.371-388, DOI:10.1093/acprof: oso/9780195179972.003.0015.

On the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on inequalities in power, for example, Liliana M. Dávalos, Rita M. Austin, Mairin A. Balisi, Rene L. Begay, Courtney A. Hofman, Melissa E. Kemp, Justin R. Lund (et al), ‘Pandemics’ Historical Role in Creating Inequality’, Science 368 (6497), 2020, pp 1322-1323.

Benjamin Enke, 2020, ‘Moral Values and Voting’, Journal of Political Economy, University of Chicago Press, vol. 128(10), 2020, pp 3679-3729; Benjamin Enke,

‘Moral Boundaries’, WORKING PAPER 31701, (Cambridge MS: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023), https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w31701/w31701.pdf.

Benjamin Enke, ‘Moral Values and Voting’, Journal of Political Economy, University of Chicago Press, vol. 128(10), 2020, pp 3679-3729; Benjamin Enke, Raymond Fisman, Luis Mota Freitas and Steven Sun., ‘Universalism and Political Representation: Evidence from the Field’.(Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023). Although

this does not mean that education and income are irrelevant. For instance, Antoine Dechezleprêtre, Adrien Fabre, Tobias Kruse, Bluebery Planterose, Ana Sanchez Chico and Stefanie Stantcheva, ‘Fighting Climate Change: International Attitudes toward Climate Policies’ (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2022), in a survey of 20 countries covering the major greenhouse gas emitters in both high- and lower income countries, show that support for climate change is associated with beliefs about the effectiveness of emissions-reduction policies, their distributional impacts on lower income households and their impact on respondents’ households. At the same time, respondents with higher levels of education and income report stronger support for climate policies, perhaps as a result of the way in which education and income interact with other factors in shaping respondents’ beliefs. Also, the extent to which beliefs, rather than economic variables, matter in the context of protecting the national environment is unclear. Matthew E Kahn and John G Matsusaka. ‘Demand for Environmental Goods: Evidence from Voting Patterns on California Initiatives’. The Journal of Law and Economics 40(1), 1997, 137-174 argue that both income and price factors, as well as beliefs, matter in the national context, at least in the state of California, United States. Aurore Grandin, Léonard Guillou, Rita Abdel Sater, Martial Foucault, Coralie Chevallier. ‘Socioeconomic Status, Time Preferences and Pro-Environmentalism’, Journal of Environmental Psychology 79, 101720, 2022 also find that economic variables matter, but through the relative position in terms of socioeconomic status—with higher status tending to be more supportive of the national environment.

Alexander W. Cappelen Benjamin Enke Bertil Tungodden, ‘Moral Universalism: Global Evidence’, Working Paper 30157, (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau Of Economic Research, 2022), http://www.nber.org/papers/w30157; Benjamin Enke, Raymond Fisman, Luis Mota Freitas and Steven Sun, ‘Universalism and Political Representation: idence from the Field’. (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023).

Bastian Becker, in ‘International Inequality and Demand for Redistribution in the Global South’, Political Science Research and Methods, 2023, pp 1-9 find that people in Kenya vastly underestimate intercountry inequalities and that when provided with the accurate degree of inequality, their tolerance for inequality declines, but their demand for international aid does not increase, suggesting that they would rather have inequalities addressed through other means. This is consistent with evidence across a wide range of countries showing that poorer people are not more supportive of redistribution (Christopher Hoy and Franziska Mager, ‘Why Are Relatively Poor People Not More Supportive of Redistribution? Evidence from a Randomized Survey Experiment across Ten Countries’. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13(4), 2021, pp 299-328.) There is evidence that views on inequality and support for redistribution within countries are linked to beliefs about the extent to which the processes that generated those inequalities are fair Ingvild Almås, Alexander W. Cappelen and Bertil Tungodden, ‘Cutthroat Capitalism Versus Cuddly Socialism: Are Americans More Meritocratic and Efficiency-Seeking Than Scandinavians?’, Journal of Political Economy 128(5), 2020, pp 1753-1788; Alexander W. Cappelen Benjamin Enke Bertil Tungodden, ‘Moral Universalism: Global Evidence’, Working Paper 30157, (Cambridge, MA: National Bureau Of Economic, 2022), http://www.nber.org/papers/w30157; Asbjørn G. Andersen, Simon Franklin, Tigabu Getahun, Andreas Kotsadam, Vincent Somville, Espen Villanger, ‘Does Wealth Reduce Support

for Redistribution? Evidence from an Ethiopian Housing Lottery’, Journal of Public Economics 224: 104939. 2023; Germán Reyes and Leonardo Gasparini, ‘Are Fairness Perceptions Shaped by Income Inequality? Evidence from Latin America’. The Journal of Economic Inequality 20(4): 893-913, 2022; Alain Cohn, Lasse J. Jessen, Marko, Klašnja and Paul Smeets, ‘Wealthy Americans and Redistribution: The Role of Fairness Preferences’, Journal of Public Economics 225: 104977, 2023.) For a recent review on preferences towards redistribution, see Friederike Mengel and Elke Weidenholzer, ‘Preferences for Redistribution’, Journal of Economic Surveys n/a(n/a), 2022, pp 1-18.

This holds even for people who are vulnerable and in need of humanitarian aid, as is often the case for refugees. Christina A Bauer, Raphael Boemelburg and Gregory M Walton, ‘Resourceful Actors, Not Weak Victims: Reframing Refugees’ Stigmatized Identity Enhances Long-Term Academic Engagement’, Psychological Science 32(12), 2021, pp1896-1906 report that reframing refugees’ identity as being, by its very nature, a source of strength and skills rather than portraying them with

a stigmatised identity as weak and unskilled victims enhanced refugees’ perseverance and boosted their confidence to help them succeed in the new host country.

Catherine C.Thomas, Nicholas G. Otis, Justin R, Abraham, Hazel Rose Markus and Gregory M. Walton, ‘Toward a Science of Delivering Aid with Dignity: Experimental Evidence and Local Forecasts from Kenya’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117(27), 2020, pp 15546-15553 emphasise that enhancing agency implies looking at a broader set of interventions beyond income transfers (see also Thomas Bossuroy, Markus Goldstein, Bassirou Karimou, Dean Karlan, Harounan Kazianga (et al) 2022, ‘Tackling Psychosocial and Capital Constraints to Alleviate Poverty’, Nature 605(7909), 2022, pp 291-297.) and that what enhances agency and confers dignity is likely to be context specific,

which implies the need to attend to cultural differences (see also Catherine Cole Thomas and Hazel Rose Markus, ‘Enculturating

the Science of International Development: Beyond the WEIRD Independent Paradigm’, Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 54(2), 2023, pp 195-214.)). There is evidence

from a large study in China that moving out of poverty does not seem to change preferences towards inequality but does reduce selfishness (Wenchao Li, Zhiming Leng, Junjian Yi and Songfa Zhong, A Multifaceted Poverty Reduction Program Has Economic and Behavioral Consequences’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 120(10): e2219078120, 2023).