Anita Bhatia serves as the Assistant Secretary- General and UN Women’s Deputy Executive Director since August 2019.Before joining UN Women, Ms. Bhatia has had a distinguished career at the World Bank Group, serving in various senior leadership and management positions, both at Headquarters and in the field. She brings extensive experience in the area of in international development, strategy, resource mobilization, strategic partnerships and organizational change management. In various positions, she led teams to deliver significant resources for scaled-up impact, including at the country level, and to craft innovative partnerships to advance development agendas and has made significant contributions to the evolving discourse on development finance. She has led diverse teams, including as Global Head of Knowledge Management, Head of Business Process Improvement and Head of Change Management. In addition to Latin America, she has worked in Africa, Europe, Central Asia and South and East Asia.Ms. Bhatia holds a BA in History from Calcutta University, an MA in Political Science from Yale University and a Juris Doctor in Law from Georgetown University.

Aparna Mehrotra has worked with the United Nations since 1983 both at HQ and in the field, in Africa, Asia and Latin America with UNDP, UNCDF and the UN Secretariat. She is currently Director, Division for Coordination of the UN System on Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women at UN Women. She co-founded and led the development and implementation of the UN System Wide Action Plan (UN-SWAP), the only UN system-wide accountability framework for gender equality and the empowerment of women. Previously, while at UNDP she led the UNDP Bureau for Latin America and the Caribbean contingent to the World Women's Conference in Beijing, co-founded the Women's Human Rights Campaign focusing on eliminating violence against women, and headed the UN Trust Fund for International Partnerships for UNDP. Subsequently, as Focal Point for Women in the UN system, Ms. Mehrotra led the development of the Directive on Sexual Harassment for the UN Military and Police contingents, and in 2004, served on deputation with the Office of the Special Adviser of the Secretary-General on Iraq supporting the establishment of the International Advisory and Monitoring Board (IAMB) set up by the Security Council. She has undergraduate and graduate degrees from Stanford University, a law degree and speaks five languages.

Background

The global outbreak of COVID-19 saw a dramatic backsliding in women’s labour force participation, a deepening feminisation of poverty, an escalating burden of unpaid care work, and an intensification of all types of violence against women and girls (‘the shadow pandemic’). Thus, now more than ever, prioritising gender equality commitments and mobilising financing for gender equality is vital to ensuring that the significant erosion of gender equality gains and women’s human rights is reversed, and that progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is put back on track. In short, building forward better demands a stronger and more concerted focus on gender equality and empowerment of women and girls.

Significant normative advancements related to gender equality and women’s empowerment have been made across the three pillars of the UN system: development; peace and security; and human rights.1 Despite this, financing for gender equality continues to fall, in both scale and scope, well below the ambitions of the normative and global financing frameworks in place. In fact, it is an area that remains chronically under- resourced – an issue that extends to gender units and gender expertise across the UN system. A study undertaken in 2017 found that only 2.03% of the UN development system’s expenditure is allocated to gender equality and women’s empowerment; and that just 2.6% of UN personnel work on the issue.2 Moreover, in humanitarian responses, a mere 1.7% of programming targets gender equality and women’s empowerment3; while an unimpressive 2% of all aid directed at peace and security in fragile states and economies addresses gender equality as a principal objective.4

These deficits have undermined efforts to deliver on gender equality commitments and priorities, and in part account for the slow and uneven progress in all 12 critical areas of concern contained in the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.5 It is also why the world is estimated to be 132 years away from achieving gender equality and women’s empowerment.6

Box 1: Financing for gender equality

Financing for gender equality, which is a necessary foundation for achieving not only gender equality but all SDGs, involves increasing the quantity and quality of financial resources for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls so that normative commitments can be translated into laws, policies, plans, budgets and meaningful implementation. The ultimate objective is to achieve tangible change and results in the lives of women and girls. In order to address current financial gaps, the Secretary-General has committed to strengthening the resource pool for gender equality in the UN system. Follow-up to the Secretary-General’s ‘Our Common Agenda’ report, together with the recommendations presented by the Secretary-General’s High-level Task Force for Financing for Gender Equality7, has provided an opportunity to deepen and standardise the implementation of financial tracking tools and financing commitments. This will help ensure the UN is ‘fit for purpose’ to deliver on gender equality as a core priority.

Tracking UN investments on gender equality and women’s empowerment: Financial markers and targets

Tracking financial allocations and expenditures on gender equality and making them public are important tools for identifying gaps between policy and finance commitments; aligning critical development and humanitarian financing flows/interventions with gender equality priorities; and mobilising additional investments/resources for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls in critical areas.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) was the first to introduce a gender equality marker as a tool for qualitatively tracking bilateral donor investments. The gender equality policy marker rates investments – using a three-point scale – on whether gender equality is addressed as a principal objective (usually through dedicated financing) or as a significant objective among a project’s various development goals. The gender equality policy marker is also applied to investments without any explicit gender equality focus to ensure that, at a minimum, they are aligned with ‘do no harm’ principles.8

Bilateral official development assistance (ODA) from OECD-DAC members for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls has been increasing consistently. Much of this growth can be attributed greater prioritisation and mainstreaming of gender concerns within other development objectives. In 2019/20, OECD-DAC members committed 45% of their bilateral ODA (corresponding to US$ 56.5 billion) to gender equality – considered a historically high level.9 As Figure 1 below shows, much of this gender-related aid in 2019/2020 – US$ 50.2 billion (or 40% of total bilateral ODA) – is not fully allocated to gender equality but to projects that integrate gender equality as one of several development objectives, only 5% of total bilateral ODA targets gender equality as a principal objective. The latter statistic has remained stagnant at this level, underscoring the need for more dedicated financing aimed at addressing the root causes of gender equality.

What the numbers and Figure 1 also highlight is that more than half of bilateral aid – or 55% – does not yet integrate a gender perspective, meaning they may be leading to – however unintended – adverse impacts on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.

Initially, the OECD-DAC applied the gender equality policy marker just to bilateral ODA. Subsequently, however, it has been extended to the full range of development financing instruments, including blended finance funds and facilities that span several sectors, such as energy, transport and the environment.

The partnership approach taken by blended finance in mobilising additional financing for implementation of the SDGs holds considerable potential for driving gender equality goals.10 Beginning in 2010, the UN Development Programme (UNDP), the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) and the UN Children's Fund (UNICEF), as well as the Peacebuilding Fund, piloted a gender equality marker in response to the Secretary-General’s Seven Point Action Plan. The Plan called for at least 15% of UN-managed funds in support of peacebuilding to be dedicated to projects whose principal objective is addressing women’s needs and advancing gender equality and women’s empowerment.11 By 2012, the gender equality marker, as well as the setting of financial benchmarks on gender equality at the entity level, had become mandatory standards under the UN System-wide Action Plan on Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UN-SWAP).12 An equivalent framework launched in 2018, the UNCT-SWAP Gender Equality Scorecard, assesses performance at the UN country team (UNCT) level against a set of harmonised standards on gender mainstreaming, including implementation of the gender equality marker.13

Through the UN-SWAP framework, which has transformed how gender equality work is carried out in the UN system, several entities have not only developed gender policies but integrated gender equality into their strategic plans and results-based management systems.

These policies and plans have helped entities better prioritise gender equality in their work through a twin-track approach to gender mainstreaming, which combines dedicated gender equality interventions with integrated approaches in programme portfolios and budgets.14 Tracking finances for gender equality, therefore, implies identifying not only standalone allocations and expenditures explicitly aimed at gender equality, but apportioning funds allocated to gender equality in those programmes in which gender equality is not the primary objective.

In 2019, the Secretary-General High-Level Task Force on Financing for Gender Equality recommended the adoption of a harmonised four-point scale gender equality marker embedded in an entity’s enterprise resource planning (ERP), applicable to all financial allocations and expenditures, and extended to UNCTs and inter-agency pooled funds. At one end of this scale are interventions addressing gender equality as a principal objective and at the other end are those not expected to contribute noticeably to gender equality.

In between are those interventions in which gender equality is integrated within other priorities, either those expected to contribute significantly to gender equality, or those expected to contribute in only a limited way. Financial tracking should be implemented at the activity level from all types of funding sources as this is the level where costs can be more accurately attributed.

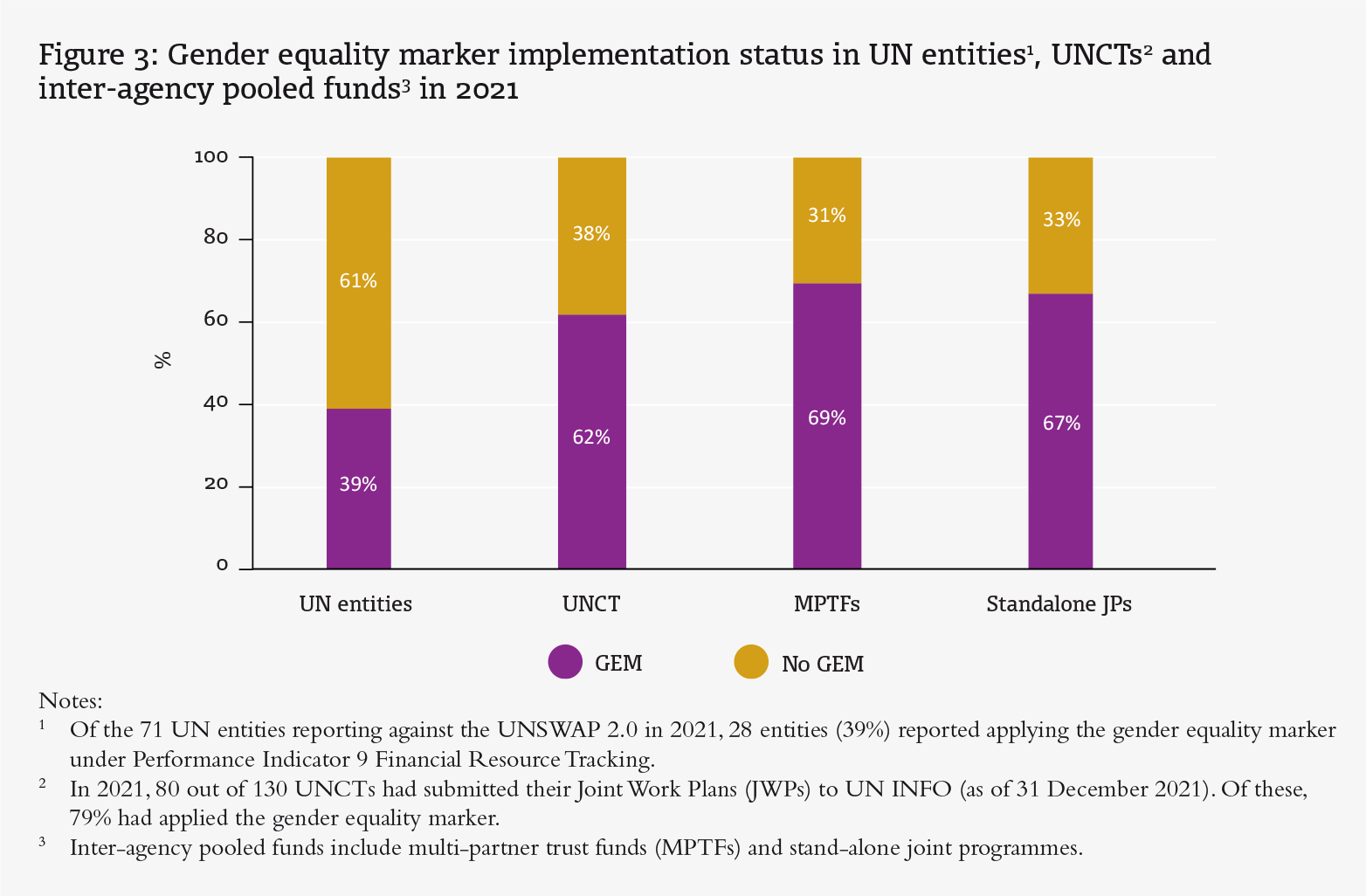

As a result, the number of UN-SWAP reporting entities applying or working towards implementing a gender equality marker has grown significantly, from 10 entities in 2012 to 28 in 2021 (see Figure 2). Much of this progress is due to the introduction of a mandatory gender equality marker in the UN Secretariat’s ERP system, which has more than tripled the number of UN Secretariat entities working to implement a financial resource mechanism tracking gender equality allocations and/ or expenditures. Another area of noteworthy progress concerns the gender equality marker’s increased application among UN funds and programmes, which doubled from five entities in 2012 to ten in 2021.

Box 2: Incentivising financing for gender equality: The COVID-19 response and recovery Multi-Partner Trust Fund

Incorporating a gender equality marker and setting a 30% financial target for gender equality allocations in the second call of the MPTF in the COVID-19 response led to a multi-fold increase in resources allocated to programmes with gender equality as a principal objective. These allocations jumped from 5% of total funding (US$ 1.9 million) in the first call to 64% (US$ 11.9 million) in the second, far exceeding the 30% target.

The combined utilisation of the gender equality marker and specific financial targets has driven increased attention in and resources for gender equality and women’s empowerment. Implementing the gender equality marker has facilitated the establishment of financial benchmarks/ targets in UN entities. Although lagging behind the advances made on financial tracking mechanisms, 23 of the 71 entities reporting to UN-SWAP 2.0 in 2022 indicated they had institutional financial benchmarks.

A recent survey found that 37% of the multi-partner trust funds and 48% of the joint programmes active in 2021 implemented financial targets for gender equality. In this regard, the Peacebuilding Fund has been one of the first inter-agency pooled funding mechanisms to demonstrate that financial targets can incentivise and mobilise additional resources for gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls.16

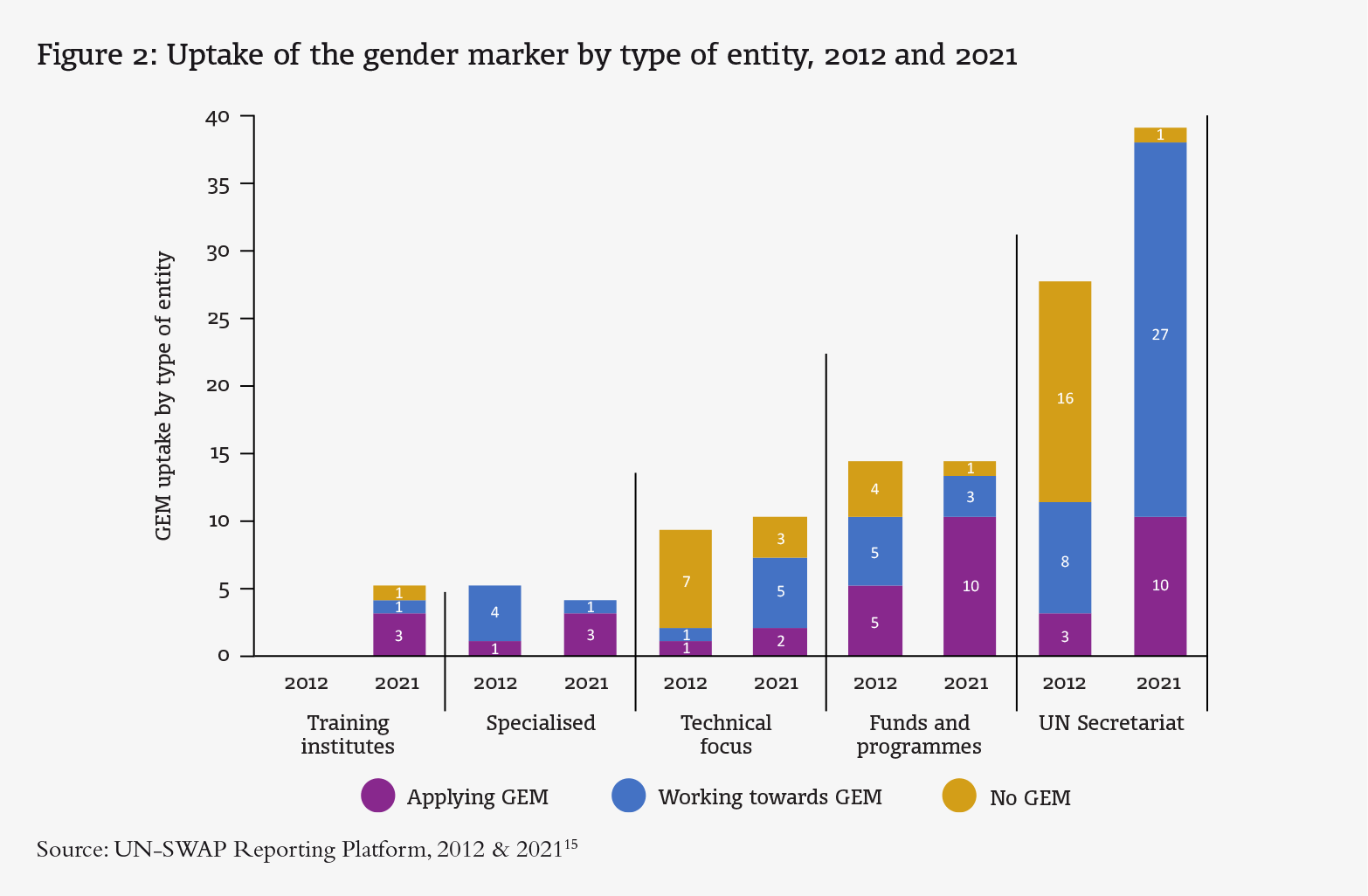

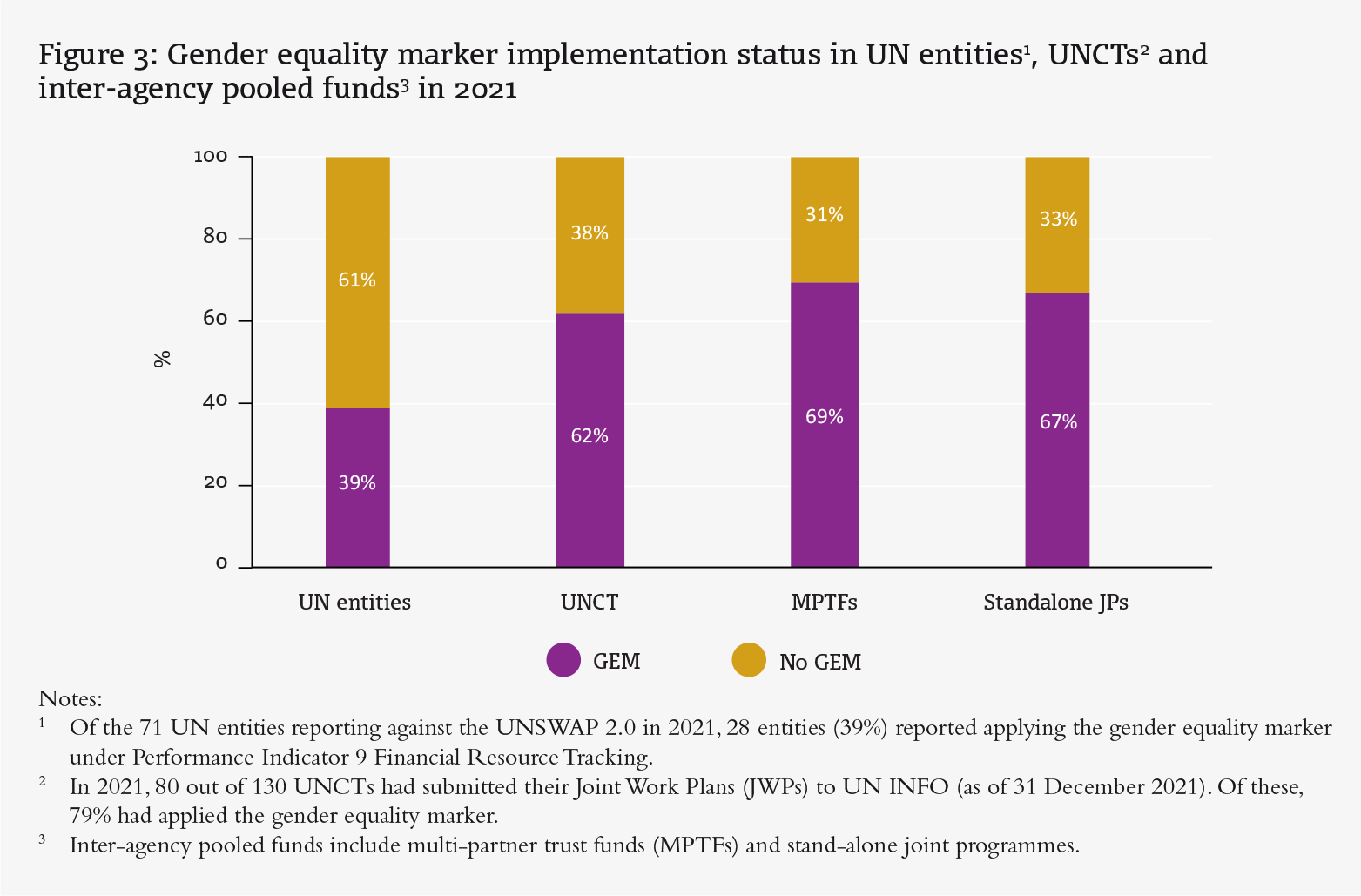

In addition to the UN-SWAP standards and the recommendations from the UN Secretary-General High-Level Task Force on Financing for Gender Equality, high-level policy directives and technology enhancements have created impetus for increased uptake of a harmonised gender equality marker not only across the UN system but in inter-agency pooled funding mechanisms and at the UNCT level (see Figure 3 below). Integration of the gender equality marker as a mandatory reporting field in UN INFO – a digital planning, monitoring and reporting platform for UNCTs – has improved access to and reporting on resources allocated to gender equality commitments across the SDGs. By the end of 2021, 80 (or 62%) of the 130 UNCTs that had entered their joint work plans into UN INFO had reported the distribution of gender equality marker codes for their funding frameworks.17

Similarly, the Partner Trust Fund Office increased efforts to embed the gender equality marker in the design and implementation of inter-agency pooled funds have succeeded in integrating the gender equality marker in 69% of multi-partner trust funds and 67% of standalone joint programmes, according to the 2021 FMOG Survey on Funding Compact Commitment 14. Moreover, financial tracking has enabled reporting of the fact that 51% of multi-partner trust funds and 71% of standalone joint programmes allocate 15% or more of their resources to programmes targeting gender equality as a principal objective.18

Entities that have been implementing the gender equality and financial targets for several years report that it has not only enabled better tracking and monitoring of gender- related resource allocations and expenditures – targeted and mainstreamed – but resulted in improved decision- making, ensured more gender-responsive planning and programming, increased resources, and enhanced institutional accountability for gender equality and women’s empowerment.

Tracking funding streams and UN system functions

While there is no widely accepted definition of what normative work is within the UN system19, setting, implementing, monitoring and reporting on international norms and standards is intrinsic to the organisation’s work, cutting across the four UN system functions of development assistance, humanitarian assistance, peace operations, and global agenda and specialised assistance.20 Such work includes facilitating intergovernmental dialogue and coordination; promotion and capacity strengthening in relation to cross-cutting norms and standards; advocacy; and the development and dissemination of normative products.

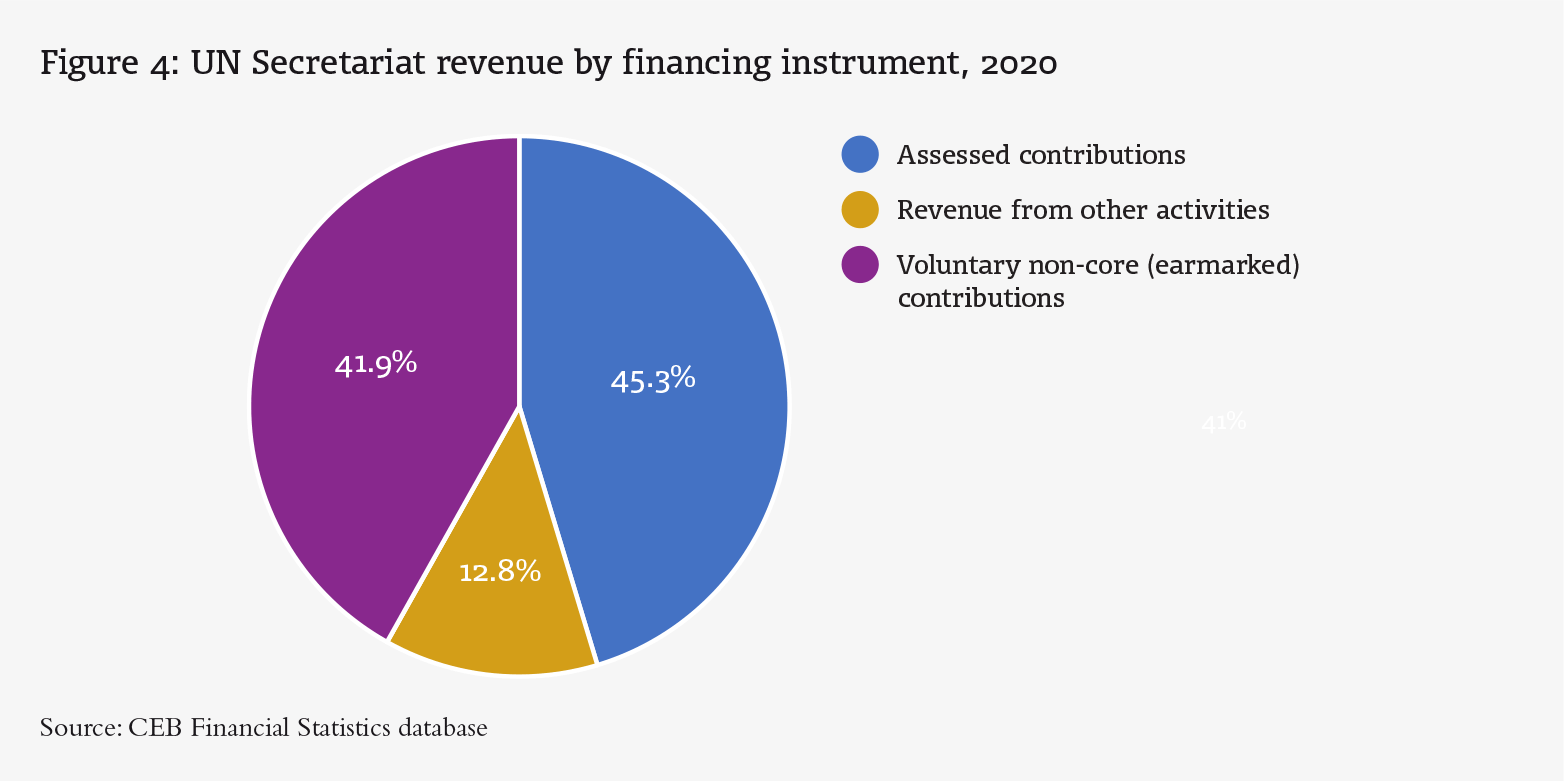

Thus far, however, UN entities are largely applying the gender equality marker to voluntary non-core contributions (or extrabudgetary (programme) funds). Only a few UN entities – namely the early adopters, UNDP, UNFPA and UNICEF, as well as the Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (ESCWA) – apply the gender equality marker to most, if not their entire, organisational budget. This covers financial allocations made to/expenditures on normative and programmatic contributions to gender equality and women’s empowerment from voluntary core/non-core contributions, fees and other revenues (if applicable).21 Most UN-SWAP reporting entities describe partial implementation of the gender equality marker, often limited to extrabudgetary, non-core funds for programmatic expenditure, rather than normative work, which tends to be funded by core allocations.

The UN Secretariat has prioritised linking resources to results for projects funded by voluntary contributions. As yet, its ERP does not financially track other sources of funds22, such as assessed contributions, for its contribution to gender equality.23 Assessed contributions, which primarily support the UN’s normative work, made up 45.3% (approximately US$ 3 billion) of the UN Secretariat’s budget in 2020 (see Figure 4 below).24

Excluding assessed contributions, and therefore financial tracking for normative work (including normative advancements on gender equality and women’s empowerment), from the scope of use of the gender equality marker not only makes it difficult to track resource allocations and expenditures in their entirety, but fails to capture an area of work at the heart of the system-wide gender equality mandate. The UN’s normative work is often tied to staff salaries, which might not directly link to programmatic components or outputs. Financial tracking should include both operations and staff costs to get a complete picture of UN system resources and expenditures.

Further complicating matters around understanding the link between resources and results, particularly for staff funding, is the weakening focus on gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls within gender units across the UN system. In a recent survey on the UN gender architecture, nearly 40% of participating UN entities reported that the remit of their gender unit was expanding to include greater focus on diversity and other inclusion issues.25 Confirming this trend, the 2022 Secretary-General report on mainstreaming a gender perspective into policies and programmes across the UN system showed that 49% of the gender units in UN entities reported addressing multiple cross-cutting issues, often resulting in a dilution of focus in support of gender equality.26 While entity size and mandate determine the type of gender architecture UN entities establish internally, the prevalent modality in the UN system involves the use of gender focal points, with an average 20% time allocation to gender equality issues. Strengthening the UN system gender architecture constitutes an essential step in the overall financing of the gender equality mandate.

Conclusion

Gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls is a UN priority and foundational to addressing the root causes of poverty, inequalities and discrimination. Achieving this aim is not only an SDG (SDG 5), but is strongly recognised as a force multiplier across all the other SDGs. Moreover, it is integral to the building and sustaining of inclusive development and peace.

Contributing to the realisation of gender equality and women’s empowerment is therefore a system-wide imperative. Here, UN Women – through its UN coordination, operational and normative mandate – has a critical role to play in ensuring gender-responsive solutions are present at the UN system level, in all processes and policy spaces, including financing for gender equality. All UN entities, UN Country Teams and inter-agency pooled funds are called to contribute to this aim through a strong gender architecture enabling coherence across the system. Although further progress is needed, recent efforts to harmonise approaches aimed at enhancing the gender equality resource base – through financial tracking and financial targets – have yielded positive results and are gaining traction. With the gender equality marker becoming part of the UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination Financial Data Standards, the UN system will be able to access more comprehensive financial information, allowing entities to better understand the financing requirements needed to realise the normative agenda on gender equality. This in turn will help ensure the UN System is adequately financed and can deliver on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’s promise.

Footnotes

Normative instruments and inter-governmental agreements that provide the guiding framework for promoting gender equality and women’s empowerment include the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (1975); the International Conference on Population and Development (1994); the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995); the Addis Ababa Action Agenda for Financing for Development (2015); the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development (2015); as well as ten UN Security Council resolutions on Women, Peace and Security, including the landmark Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000).

Dalberg,‘System-wide Outline of the Functions and Capacities of the UN Development System’, June 2017, www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www. un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/qcpr/sg-report-dalberg_unds-outline-of- functions-and-capacities-june-2017.pdf.The estimates are based on development funding commitments made for gender equality, where entity data is available.

UNWomen and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA),‘Funding for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and Girls in Humanitarian Programming’, 2020, www.unfpa.org/publications/ funding-gender-equality-and-empowerment-women-and-girls- humanitarian-programming.

The Beijing Platform for Action’s 12 areas of critical concern consist of: women and poverty; education and training of women; women and health; violence against women; women and armed conflict; women and the economy; women in power and decision-making; institutional mechanisms for the advancement of women; human rights of women; women and the media; women and the environment; and the girl-child. UN Inter-Agency Network on Women and Gender Equality (IANWGE), ‘25 Years After Beijing: A Review of the UN System’s Support for the Implementation of the Platform for Action, 2014–2019’, 2020, www. unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2020/09/ianwge-review- of-un-system-support-for-implementation-of-platform-for-action.

World Economic Forum, Global Gender Gap Report 2022 (Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2022), p. 5, www.weforum.org/reports/global- gender-gap-report-2022.

The High-Level Task Force on Financing for Gender Equality was established by the Secretary-General’s Executive Committee to review and track UN budgets and expenditures across the system and make recommendations on how to increase financing for gender equality, including by identifying any structural and operational changes required to enable financial tracking. See UN Women, High-Level Task Force on Financing for Gender Equality', https:// gendercoordinationandmainstreaming.unwomen.org/building-block/ high-level-task-force-financing-gender-equality.

OECD, Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women and Girls: Guidance for Development Partners (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022), p. 102, https://doi.org/10.1787/0bddfa8f-en.

UN General Assembly and UN Security Council,‘Women’s participation in peacebuilding: Report of the Secretary-General’, A/65/354–S/2010/466, 7 September 2010, p. 12, https://undocs. org/A/65/654.

Launched in 2012 and updated in 2018, UN-SWAP is a UN System Chief Executives Board for Coordination (CEB)-endorsed accountability framework consisting of 17 performance indicators. It comes under the leadership and stewardship of UN Women and aims to facilitate implementation of the CEB’s 2006 UN System-Wide Policy on Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women, focusing on results and impact. See CEB, ‘UN System-Wide Action Plan on Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (SWAP)’, https://unsceb. org/un-system-wide-action-plan-gender-equality-and-empowerment- women-swap.

UNWomen,‘Handbook on Gender Mainstreaming for Gender Equality Results’, 2022, p. 19, www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/ publications/2022/02/handbook-on-gender-mainstreaming-for-gender- equality-results.

In 2020, the Peacebuilding Fund approved investments of US$ 173 million in 41 contexts, allocating 40% of this towards improving gender equality, the same share as the previous two years, surpassing its 30% financial target for gender equality. See UN Security Council,‘Women and peace and security: Report of the Secretary-General’, S/2021/827, 27 September 2021, https://undocs.org/S/2021/827.

Data can be accessed at UN INFO, ‘Data explorer’, https://uninfo.org/ data-explorer/cooperation-framework/activity-report.

UN ECOSOC,‘Annex: QCPR Monitoring Framework, 2021–24’, www.un.org/ecosoc/sites/www.un.org.ecosoc/files/files/en/ qcpr/2022/QCPR-Structure-MF-Footnotes-22Apr2022.pdf.

According to the UN Evaluation Group, normative work in the UN encompasses three dimensions, namely,‘support to the development of norms and standards in conventions, declarations, regulatory frameworks, agreements, guidelines, codes of practice and other standard setting instruments, at global, regional and national level’; support for the integration of these norms and standards into legislation, policies and development plans; and the subsequent implementation of such legislation, policies and development plans. See UN Evaluation Group (UNEG), ‘UNEG Handbook for Conducting Evaluations of Normative Work in the UN System’, November 2013, p. 5, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/uneg- handbook-conducting-evaluations-normative-work-un-system.

UN Sustainable Development Group (UNSDG) and CEB,‘Data Standards for United Nations System-wide Reporting of Financial Data’, March 2022, p. 13, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/data-standards- united-nations-system-wide-reporting-financial-data

The budgets of UNDP, UNFPA and UNICEF do not receive assessed contributions. See Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation and UN Multi- Partner Trust Fund Office (UN MPTFO), Financing the UN Development System:Time to Meet the Moment (Uppsala/New York: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation/UN MPTFO, 2021), p. 11, www.daghammarskjold.se/ publication/unds-2021/.

CEB Financial Statistics database, https://unsceb.org/financial-statistics.

UNWomen,‘Coordination for gender equality and the empowerment of women’, https://gendercoordinationandmainstreaming.unwomen.org/.