Briony Coulson is Head of International Sustainable Blue Finance at the United Kingdom’s (UK) Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. She brings 15 plus years of experience on environment issues, with the majority of that time in the UK Government specialising in International Environment Negotiations and delivery of UK Aid programmes on natural resource management. Briony Coulson currently manages the UK’s Blue Planet Fund, a GB£ 500 million programme working in partnership with developing countries to build sustainable marine economies. She manages a suite of programmes that provide technical assistance on tackling pollution, Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) and sustainable fisheries. Briony Coulson is the Co-Chair of the Global Fund for Coral Reefs from 2022-2024, alongside the United Nations Environment Programme.

Pierre Bardoux is Head of the Global Fund for Coral Reefs (GFCR) and Nature Asset Team at United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) with 15 plus years of experience in innovative finance and implementation for biodiversity conservation. He designs innovative blended finance instruments across UN agencies and mandates, mobilising action from governmental institutions, development actors, and responsible private companies and investors. Pierre Bardoux is leading the GFCR UN Team and designed a catalytic model now serving as the largest UN global blended finance instrument dedicated to Sustainable Development Goal 14, Life Below Water. Through his position as a Senior Portfolio Manager in the UN Multi Partner Trust Fund Office, he established and managed an active portfolio of climate and environmental trust funds focused totalling over US$ 2.5 billion. Prior to this, he worked for more than a decade with United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Country Offices, UN Peacekeeping Operations, and the International Crisis Group in Central Africa. Pierre is currently based in New York.

Introduction

Biodiversity encompasses the rich variety of life on Earth and the abundant services its ecosystems provide. While the primary Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) addressing nature are 14 and 15, to conserve and sustainably use the marine and terrestrial environment, the achievement of all 17 SDGs is ultimately dependent on thriving biodiversity.

In recent decades the health and extent of nature has continued to decline. Studies estimate that wildlife populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, and fish have seen an average decline by 69% since 1970.1 The lack of action to save Earth’s remaining biodiversity is viewed as one of the most rapidly increasing global risks over the next decade.2 As acknowledgement of the shared risks associated with the collapse of ecosystems has risen within public and private realms, so has the understanding of the private sector’s potential to help close conservation funding gaps.3

In biodiversity forums, the role of the private sector in identifying, financing, and scaling sustainable solutions that address biodiversity loss is taking centre stage. From blended finance mechanisms to blue and green bonds, debt-for-nature swaps, and biodiversity credit systems, conservation finance tools are on the rise.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) adopted by 196 nations in December 2022 emphasises the need for diversified conservation funding sources.4 Notable is GBF Target 19 aiming to mobilise at least US$ 200 billion annually in domestic and international biodiversity-related funding from all sources – public and private – by 2030.5 This will be contributing to the goal of protecting 30% of terrestrial and inland water areas and marine and coastal areas. The text further emphasises the promotion of blended finance and encouragement for the private sector to invest in biodiversity, including through impact funds and calls on the international community to increase biodiversity financing to Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS).

Blended Finance SDG Investment Pathways

This sweeping agreement to accelerate financial flows from all sources has resulted in the identification of blended finance vehicles being a key catalyst. In the midst of the December 2022 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) Conference of the Parties (COP15), thirteen donor countries and the European Union (EU) committed to ‘encourage investments in biodiversity by the private sector, including through blended financing mechanisms and other innovative approaches which mobilise public and private finance’.6 The statement further went on to identify investment-ready mechanisms, including the Global Fund for Coral Reefs (GFCR).

The GFCR was launched in September of 2020 by founding partners Paul G. Allen Family Foundation, Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation, International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI), United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). The initiative features a private equity fund managed by Pegasus Capital Advisors and an UN-managed grant fund. The GFCR has convened a powerful coalition of coral nations, donor states, philanthropies, impact investors, strategic partners, and UN agencies to increase the protection of Earth’s most climate-resilient coral reefs.

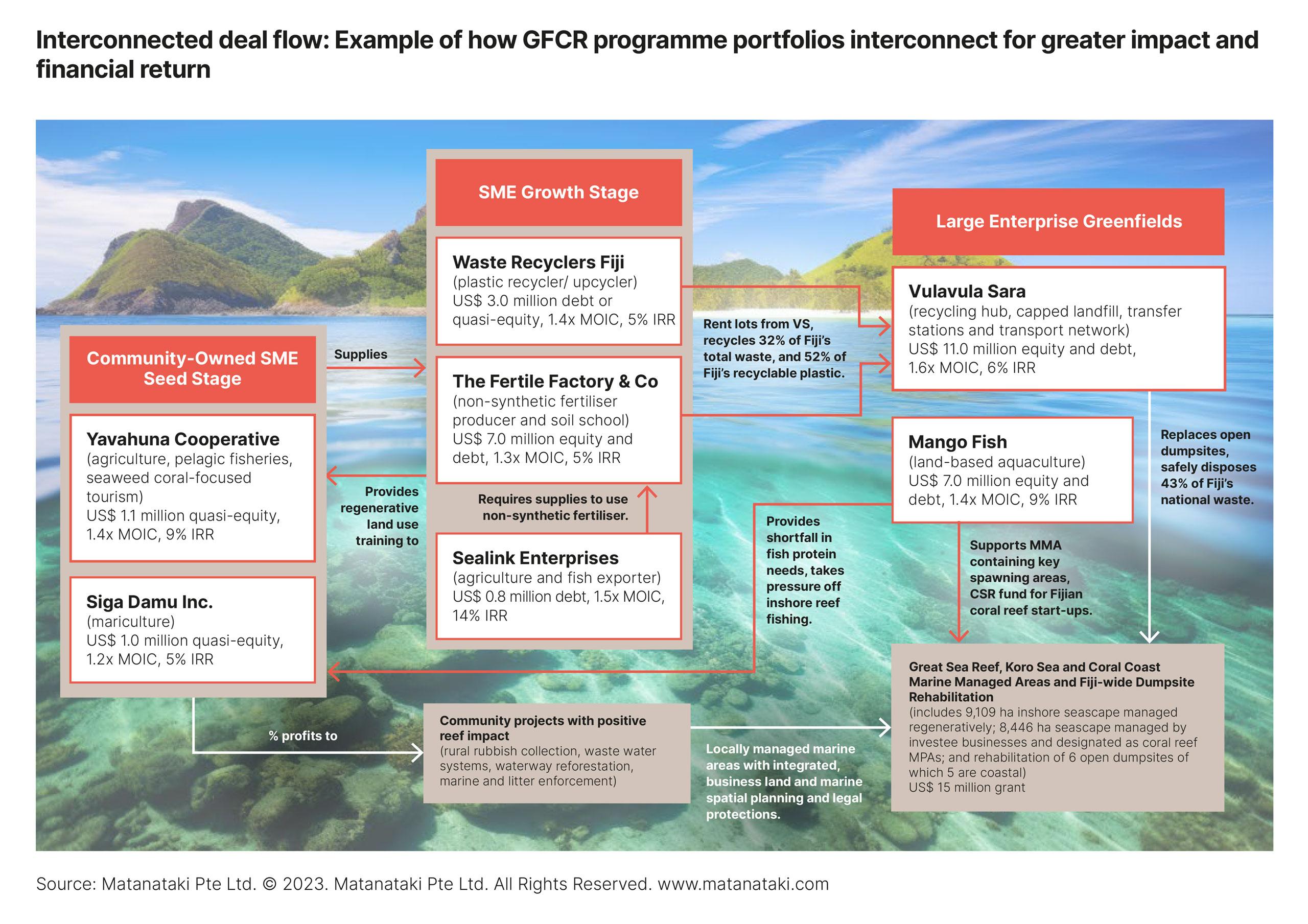

GFCR blends public and private capital at multiple levels. At the global level, both philanthropic and state donors have joined forces to capitalise the grant fund. The grant fund, a UN multi-partner trust fund, is a pooled finance vehicle equipped with catalytic functions including recoverable grants, performance-based grants, concessional loans, and technical assistance. GFCR’s grant fund programmes are designed to bolster local community and conservation benefits from larger private equity investments, including through connectivity of small and medium-sized ‘reef-positive’ enterprises into the supply chain of larger ventures.

As GCF’s first at-scale private sector initiative in the blue economy, the commitment is intended to de-risk investments for private investors at the fund level, thereby bridging the gap between public and private investors.

Through a lens of sustainable reef-positive economic transition, GFCR utilises a resilience-based management (RBM) strategy to guide programme design and implemen-tation. Programmes focus on identifying, incubating, and scaling bankable solutions and financial mechanisms that help address local drivers of coral reef degradation, unlock sustainable conservation funding flows, and increase coastal communities’ resilience to climate impacts. While RBM does not prevent the damaging impacts of climate change, it may offer coral reefs the best chance of avoiding functional extinction in the 21st century.7

At the time of writing the GFCR’s growing portfolio has blended finance programmes underway for over 20 countries, more than 60% of which include SIDS and LDCs harbouring Earth’s most climate-resilient reefs. Supported solutions include waste treatment and recycling facilities, coral reef insurance, sustainable aquaculture and agriculture, ecotourism enterprises, blue carbon credits, and sustain-able finance mechanisms for Marine Protected Areas (MPAs).

In Fiji, the first programme launched by GFCR, grant funding and co-financing from the Joint SDG Fund are deployed to support a local incubator, Matanataki, to identify, support and scale locally driven conservation solutions. Two transactions underway in the initial programme phase include an organic fertiliser company to reduce eutrophication and sedimentation from the sugar cane sector and a waste management facility with a recycling component to reduce land-based solid waste leaching onto Fiji’s coral reefs. Both initiatives have attracted great interest by local and international investors with a further influx of private investment capital expected in 2023. Additional solutions in Fiji, including shark-based ecotourism tied to MPA finance, are now receiving support to expand conservation impact and community benefits.

Catalytic UN Multi-Partner Trust Funds

The design of a UN multi-partner trust fund to de-risk, attract, and bolster private investment for conservation impact has been highly welcomed by leading international donors. The catalytic use of funds enables donors to support initiatives that increase sustainable livelihoods, local resilience, and conservation impacts, without requiring long-term dependence on aid. By using grant funds to reduce specific investment risks, donors are unlocking pioneering investments in regions which would normally be overlooked through a strictly commercial scope.

As one of the largest donors to UN multi-partner trust funds, the Government of the United Kingdom (UK) recently increased its commitment to the GFCR to GB£ 33 million via a contribution from the country’s GB£ 500 million Blue Planet Fund. By exploring and supporting innovative solutions, such as blended finance mechanisms the Blue Planet Fund, jointly led by the UK Department for Environment and Rural Affairs (Defra) and the Foreign Commonwealth Development Office (FCDO) supports a portfolio of programmes that protect and enhance marine ecosystems. The Blue Planet Fund promotes the conservation and sustainable management of ocean resources, ensuring long-term impacts for the most vulnerable communities while accelerating action to tackle the biodiversity crisis and reduce critical funding gaps.

As the largest donor to the GFCR, the UK has continued to demonstrate global leadership on the ocean, by scaling blended finance in developing countries. It is through its partnership with the GFCR that the UK has found an opportunity to fund critical projects strategically linked with its international objectives and the ambitions of the Blue Planet Fund, whilst also supporting the GFCR to leverage millions of dollars of blue finance to further protect coral reefs and the communities that depend on them.

As a key part of the GFCR Coalition and as co-chair of the Executive Board, working through a UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund enables the UK to support delivery of bold initiatives and push for higher ambitions within coral reef conservation and sustainable development through the protection, enhancement, and sustainable management of marine resources. The GFCR has made a wealth of progress since its inception in 2020, with a total of 18 programmes currently in implementation or under development, and fundraising efforts coming into fruition with the UK’s GB£ 33 million complementing the new Minderoo Foundation contribution of AU$ 5 million to the investment fund.

Overall, there is a great deal that still needs to be done to encourage global private finance flows to become ‘nature-positive’ and support climate resilience in developing countries. Development assistance positioned through pooled finance vehicles designed to complement and enhance impact of private investment can play an important role in accelerating biodiversity-related funding from all sources.

As we face one of the biggest threats ever witnessed in modern times, the deterioration of our natural environment, we have before us hope and opportunity through blended finance pathways. The 10 Point Plan for Financing Biodiversity, developed by the UK, Ecuador, the Maldives, and Gabon, provides a clear roadmap defining the role of finance sources needed to deliver the Global Biodiversity Framework.8 The plan is endorsed and heavily supported by over 42 countries, however continued collaboration and innovation is vital to sustain ambition, to mobilise resources from all sources and to focus collective efforts to deliver on the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Endnotes

WWF (2022) ‘Living Planet Report 2022 – Building a nature- positive society’. Almond, R.E.A., Grooten, M., Juffe Bignoli, D. & Petersen, T. (Eds). (Gland: WWF, 2022), https://livingplanet.panda.org/en-US/.

World Economic Forum (WEF), ‘Global Risks Report’, (Geneva: World Economic Forum, 2023), https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-risks-report-2023/.

Andrew Deutz, Geoffrey M. Heal, Rose Niu, Eric Swanson, Terry Townshend, Zhu Li, Alejandro Delmar, Alqayam Meghji, Suresh A. Sethi, and John Tobin-de la Puente, ‘Financing Nature: Closing the global biodiversity financing gap’, The Paulson Institute, The Nature Conservancy, and the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, 2020, https://www.paulsoninstitute.org/conservation/financing-nature-report/.

Convention of Biodiversity Secretariat, Cop15, ‘Nations Adopt Four Goals, 23 Targets For 2030 In Landmark UN Biodiversity Agreement’, 19 December 2022, https://www.cbd.int/article/cop15-cbd-press-release-final-19dec2022.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), ‘Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework’,CBD/COP/DEC/15/4, (Nairobi: UNEP, 2022), https://www.cbd.int/doc/decisions/cop-15/cop-15-dec-04-en.pdf.

Government of the United Kingdom Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, et al, ‘Joint Donor Statement on International Finance for Biodiversity and Nature’, 16 December 2022, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/joint-donor-statement-on-int….

Elizabeth Mcleod, et al, ‘The Future Of Resilience-Based Management In Coral Reef Ecosystems’, Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 233,1 March 2019, Pages 291-301, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0301479718312994.