The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth (OSGEY) works with and for young people globally to strengthen meaningful youth engagement at the UN and in inter-governmental policy and decision-making processes. Guided by the system-wide Youth 2030 strategy1 and carrying out global-level advocacy and outreach efforts, OSGEY is led by the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth, Jayathma Wickramanayake.2

The United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY) is a global network of 130 youth-led organisations in 70 countries. It is dedicated to building and sustaining peace from the ground up across a wide range of peace and security topics, and at all stages of the conflict cycle. This includes working towards ending the violence of young people’s exclusion by transforming the power structures that exclude them from decision-making; building sustainable spaces for young people to shape the decisions that affect them; and connecting people so that they can partner for peaceful and inclusive societies.

Introduction

Young people play a critical role in efforts for building and sustaining peace. A growing body of evidence demonstrates their importance as mediators, community mobilisers and advocates collaborating across borders to prevent conflict and maintain peace.3 Through these roles, they strengthen the reach and credibility of peacebuilding programmes within marginalised communities; mobilise powerful social change movements; and employ innovative, intersectional approaches to peacebuilding and conflict prevention. The adoption of three Youth, Peace and Security (YPS) resolutions by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is strong recognition of the important positive roles and intersectional approaches by which young people contribute to building and maintaining peace.4 As such, the resolutions place meaningful participation and inclusion of young people at the front and centre of peace and security.5 UNSC Resolution 2250 also urges Member States to increase ‘their political, financial, technical and logistical support [for] the needs and participation of youth in peace efforts’.6

Additionally, the UN General Assembly adopted the Financing for Peacebuilding Resolution in 2022, which recognises the persistent challenges young people face in accessing resources. Specifically, it calls for ‘efforts to address existing financing gaps for youth-led initiatives and youth organisations to ensure the full, effective and meaningful participation of youth in the design, monitoring, and implementation of peacebuilding efforts at all levels, and encourages all financing stakeholders to increase coordination and collaboration with youth on financing national priorities’.7

The current global population count sets the number of youth aged 18–29 at more than 1.8 billion – the largest age group in the world.8 Moreover, youth often constitute most of the inhabitants in conflict-affected contexts.9 Ensuring that young people’s participation in peace efforts is coupled with sufficient resources is therefore crucial.

Renewed investment by Member States and other donors is necessary to ensure that the UN meets its commitments on engaging young people as equal partners in peacebuilding. Additionally, the allocation of existing funds within the UN system should be increasingly directed to YPS. Therefore, this article provides a brief analysis of the current state of financing for the YPS agenda, including youth-led peacebuilding, within the UN system, and outlines recommendations to strengthen these investments.

Where are we at?

Data on financing of the YPS agenda in the UN system

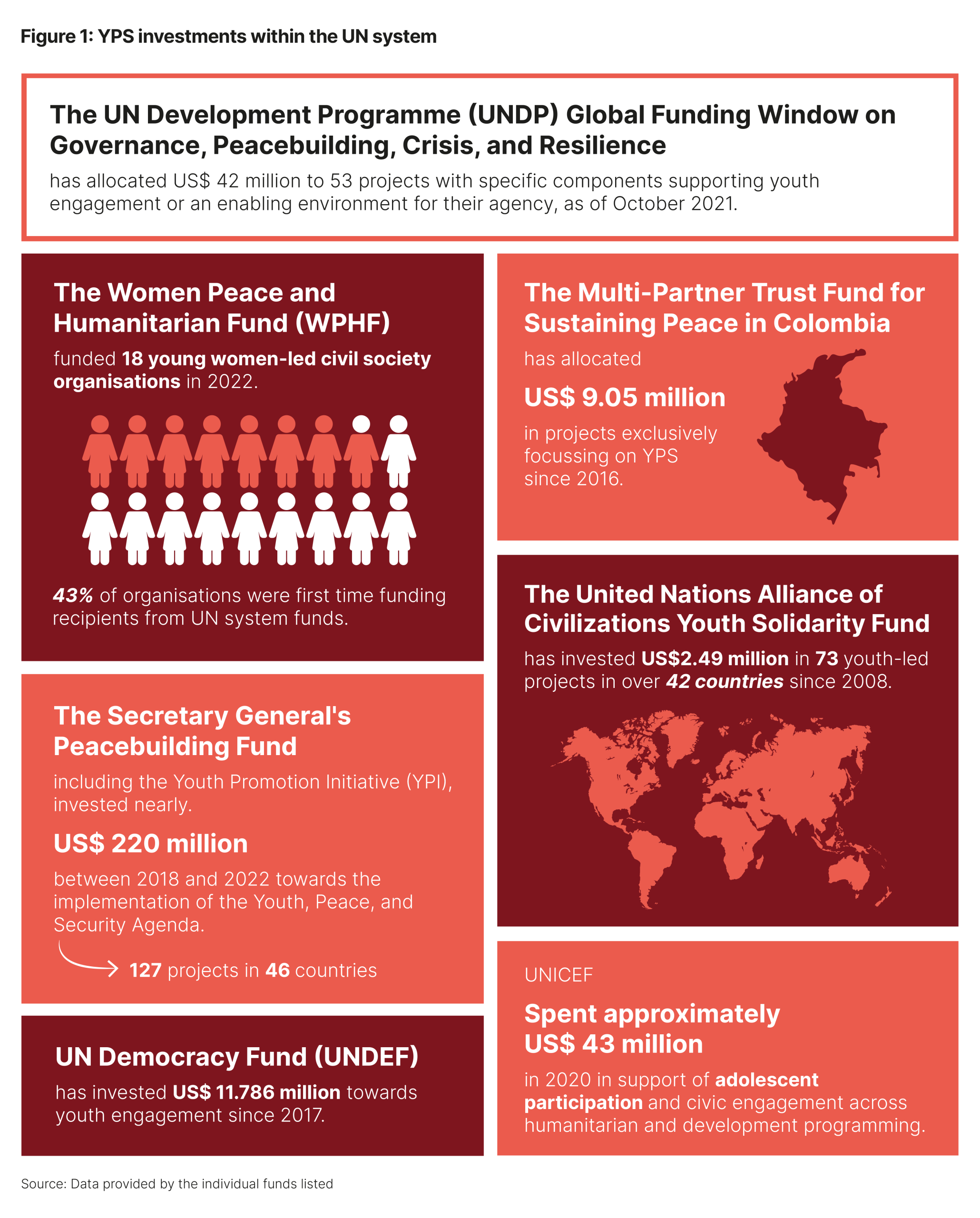

The funding landscape for YPS within the UN system is limited, concentrated in only a few funds, with very little support for youth-led efforts. While existing data is limited, Figure 1 gives an overview of several sources of investment, providing insight into YPS investments within the UN system. Altogether, the five funds included in the Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Funding Dashboard allocated US$ 1.083 billion towards peacebuilding during the period 2015–2021.10 However, only 10.63% of these resources went towards youth empowerment and participation, with significant fluctuation from year to year.11 Although there is no disaggregated data on how much of this percentage specifically went towards youth-led efforts, it is likely to be a very small proportion – a recent survey demonstrated that 49% of youth-led organisations operate on less than US$ 5,000 annually.12

Accessibility of UN’s funding mechanisms to youth-led organisations

Most of the existing financing modalities within the UN system incorporate stringent eligibility criteria and fiduciary requirements, as well as overburdensome application and reporting requirements. These requirements remain challenging for youth organisations, which usually lack the structures and capacity to access and report on the funds. Especially youth who are left behind are less likely to access funding.13

These young people are those who are the furthest left behind while they face added barriers to the social, political and economic opportunities enjoyed by their peers.14 This group includes young women and gender-diverse youth, rural youth, indigenous youth and young people with disabilities. Additionally, most of the funding available to youth-led organisations is project-based and short-term. This forces youth-led organisations to adapt to donor priorities rather than responding to the needs of their local context. It also undermines the sustainability of youth-led civil society, as the lack of predictable funding limits organisational growth.

In addition, conceptualisation and design processes for UN system programmes and strategies – including among UN agencies and funds – frequently lack meaningful engage-ment of diverse youth, which should be the starting point. At the country level, lack of financing for youth-inclusive consultation processes places a significant limitation on UN country teams’ efforts to meaningfully engage young people in programme and strategy design. This results in frequent mismatches between how available funding is allocated and the priorities raised by young people in peacebuilding contexts. Only 40% of UN entities have at least some resources allocated to meaningful youth engagement.15

There are positive examples within and outside the UN system that can guide future efforts to make funding more accessible and responsive to young people’s needs. As an example, the Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund has adopted a model in which civil society organisations are integrated into the fund’s governing board and in-country steering committees.17 This allows for greater influence in defining priorities for the allocation of resources.

Outside the UN system, the use of participatory grant-making models engages young people in funding process design and decision-making. Results so far have demon-strated greater responsiveness to young people’s needs and consequential ownership. As an example, since 2020, the Global Resilience Fund has channelled over US$ 1 million in bilateral, multilateral and philanthropic funds to organisa-tions led by girls and young feminists. The fund has rapidly distributed resources based on the funding needs, priorities and perspectives identified by community-level actors.18

Data gap on financing the YPS agenda

One of the largest barriers to advancing financing of the YPS agenda is a lack of data. This limits analysis of the amount, quality and focus of funding allocated to supporting youth-led and youth-focused peacebuilding. However, existing data indicates that both youth-led and youth-focused peacebuilding are not sufficiently resourced.

To date, the UN system does not disaggregate collected data on financing peacebuilding based on age. This significantly limits the evidence base available for identifying the financing needs of youth-led community service organisations (CSOs). In order to ensure no one is left behind, there is a particular need to incorporate marginalised youth groups within future data collected by the UN system. Despite efforts by some UN entities to improve data disaggregation and tracking, more needs to be done to strengthen data disaggregation using a diverse youth lens.19

Improved data collection would not only allow informed policy, strategy and financing regarding the YPS agenda, it would also enable greater coordination and integration of YPS perspectives across the humanitarian, peace and development nexus. For example, adoption of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Gender Equality Marker has helped inform analysis, including an OECD paper that ‘provides guidance and actions derived from promising practices that can be taken to strengthen the role of gender equality within members’ nexus strategies’.20

What is needed?

How do we move towards strengthened coordination and joint programming?

In September 2021, the UN Secretary-General launched Our Common Agenda, outlining a vision for how the UN system can accelerate implementation of existing agreements, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This comes at a time when the world is facing multiple emerging global challenges, including multi-pronged crises, growing inequalities, ongoing conflicts and diminishing official development assistance (ODA).

To successfully tackle these challenges, it is crucial to transform the financing landscape. Strategic, long-term, and flexible approaches are required from the donor community. However, the practice of strict earmarking of funds within the UN system disincentivises these approaches. The percentage of funding within the UN system which is earmarked has grown from 51% in 2010 to 60.7% in 2022.

The UN system-wide Youth 2030 strategy seeks to ensure that the UN’s work on youth issues is pursued in a coordinated, coherent and holistic manner. It provides a strategic framework for reinforcing cooperation and joint programming among diverse UN entities across all pillars of the organisation, including peace and security, human rights, and sustainable development. Under the Youth 2030 thematic priority area of building peace and resilience, initial steps towards joint programmatic efforts are already being taken. As an example, the UN Population Fund and the Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) have partnered with the UN Development Programme, UN Women and the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to strengthen the capacities of UN staff in designing and delivering better gender-and-youth-responsive peacebuilding programmes. This was done through two trainings in 2022 that targeted UN staff from PBF-eligible countries.21

However, strengthened coordination and cooperation between UN entities is still needed to ensure efficient, strategic use of limited resources, and to effectively respond to interconnected crises in an intersectional manner. This requires further intergenerational collaboration with CSO partners on joint YPS programming to foster a more collaborative environment.

Recommendations and opportunities

Financing of the YPS agenda needs to be strengthened if the UN is to meet its responsibility to young people and unlock their potential to accelerate implementation of the SDGs. To do so, it is critical that donors and UN entities build on their commitments and make concrete, evidence-informed investments in YPS, including young people’s role in peacebuilding.22 With this in mind, the recommendations (below) identify concrete next steps to: improve the quantity and quality of funding; integrate young people into programming and strategy development; improve data on funding; and strengthen coordination and collaboration between UN entities and civil society partners, including youth-led civil society.

Improve the quantity and quality of funding: Member States and UN entities should ensure flexible, long-term and sustainable investment in youth-led and youth-focused peacebuilding and prevention efforts. For Member States, this could include setting aside minimum allocations of their ODA. These funds should be accessible to youth-led organisations, including those led by young women and gender-diverse youth.

Integrate meaningful engagement of young people into programming and strategy development: Networks of youth organisations can play an important role in facilitating access to diverse youth organisations. However, this engage ment must be properly resourced in order to facilitate meaningful access for a diverse array of youth groups, including marginalised youth.23

Improve data on funding: Member States and UN entities should develop data systems that track investments in young people similar to those tracking funding for gender equality.24 In addition, multilateral actors should increase investment in data that can help in understanding the impact of youth-led and -serving peacebuilding.

Increase investments in, and strengthen incentives for, joint programming and improved collaboration between UN entities and civil society partners: To meet the complex and context-specific challenges faced by young people, donors must increase flexible funding and incentivise both strengthened coordination within the UN system and collaboration with young people.

Sustainable and youth-inclusive peacebuilding will only be guaranteed if the listed recommendations are put into action.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to the following entities and organisations, all of which contributed to this article: Dag Hammarskjöld Foundation, Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs, Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict, Search for Common Ground, United Nations Alliance of Civilizations and UNICEF.

Endnotes

United Nations, ‘Youth 2030: Working With and For Young People – United Nations Youth Strategy’, 2018, www.unyouth2030. com/_files/ugd/b1d674_9f63445fc5- 9a41b6bb50cbd4f800922b.pdf.

African Union, ‘A Study on the Roles and Contributions of Youth to Peace and Security in Africa: An Independent Expert Report Commissioned by the Peace and Security Council of the African Union’, 2020, www. peaceau.org/uploads/au-study-youth-africa-web.pdf; United Network of Young Peacebuilders (UNOY) and Search for Common Ground (SFCG) and, ‘Mapping a Sector: Bridging the Evidence Gap on Youth-Driven Peacebuilding’, 2017, https://unoy.org/downloads/mapping-a-sector-bridging-the-evidence-gap-o…; and Ali Altiok and Irena Grizelj, ‘We Are Here: An Integrated Approach to Youth-inclusive Peace Processes’, UN Office of the Secretary General’s Envoy on Youth, 2019, https://youth4peace.info/book-page/global-policy-paper-we-are-here-inte….

Graeme Simpson, The Missing Peace: Independent Progress Study on Youth, Peace and Security, (New York: UNFPA and UN Peacebuilding Support Office, 2018), https://youth4peace.info/ProgressStudy;

UN Security Council Resolution 2535, 14 July 2020, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3872061?ln=en; UN Security Council Resolution 2419, 6 June 2018, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1628896?ln=en; and UN Security Council Resolution 2250, 9 December 2015, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/814032?ln=en. UN Security Council Resolution 2282, 27 April 2016, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/827390?ln=en; UN General Assembly Resolution 70/262, 27 April 2016, https://undocs.org/A/RES/70/262; UN Security Council Resolution 2558, 21 December 2020, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3895721?ln=en; UN General Assembly Resolution 75/201, 21 December 2020, https://undocs.org/A/RES/75/201.

UN General Assembly Resolution 76/305, 8 September 2022, https://undocs.org/A/RES/76/305.

UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), Population Division, ‘World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results’, 2022, www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa. pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf.

The five funds are: 1) the Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund; 2) the UN Alliance of Civilisations Youth Solidarity Fund; 3) the UN–World Bank Partnership Humanitarian Development Peace Partnership Facility; 4) the UN Fund to Support Cooperation on Arms Regulation; and 5) the Women, Peace and Humanitarian Fund.

UN Sustainable Development Group, ‘Leave No One Behind’, https://unsdg.un.org/2030-agenda/universal-values/leave-no-one-behind.

Office of the Secretary General’s Envoy on Youth (OSGEY), ‘Youth2030: A Global Progress Report, 2022’, 2022, p. 60, http://www.unyouth2030.com/progressreport.

Women’s Peace & Humanitarian Fund, ‘Operations Manual’, December 2021, https://wphfund.org/our-mission/.

Global Resilience Fund, ‘Weathering the Storm: Resourcing Girls and Young Activists Through a Pandemic’, May 2021, www. theglobalresiliencefund.org/report. For other examples of participatory models see the Frida Feminist Fund (https://youngfeministfund.org), the Global Partnership for the Prevention of Armed Conflict (https://gppac.net/files/2021-12/For%20Youth%20and%20By%20Youth%20 Re-Imagining%20Financing%20For%20 Peacebuilding.pdf), and the Youth 360 model (www.sfcg.org/youth-360/).

For a full analysis see UNICEF (note 13). UNICEF has recently adopted an ‘adolescent tag’, which enables the organisation to track and analyse yearly expenditures going towards improving adolescent and young people’s access to quality basic social services and supporting their civic engagement and participation.

In 17–19 May 2022, a training was held in Thiès, Senegal, for 40 UN staff members from eight PBF-eligible UN country teams (Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania and Sierra Leone). In 6–8 December 2022, a training was conducted in Nairobi for 53 UN staff members, targeting a group of 12 PBF-eligible countries (including the Central African Republic, Colombia, Guatemala, the Republic of Guinea, Haiti, Niger, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Gambia. The training also included teams from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Madagascar).

UNOY, ‘Meaningful Youth Engagement Checklist’, 2021, https://unoy.org/downloads/mye-checklist/.